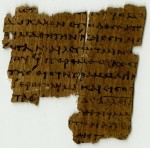

Nonexistent? Okay then, how are you at playing Concentration when you can see all the cards? Pretty damn good, I bet. Well now you can put that talent to excellent history nerd use by helping identify and transcribe the Oxyrynchus Papyri, a large collection of ancient writings dating from the 1st to the 6th century A.D.

Archaeologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt discovered thousands of papyri in a garbage dump outside Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, in the winter of 1896. The papyri had been preserved by the dry sand and were primarily written in Greek, although there were also Latin and later Arabic documents in the mix. The discovery generated immense excitement, with visions of the lost works of antiquity dancing in people’s heads.

Archaeologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt discovered thousands of papyri in a garbage dump outside Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, in the winter of 1896. The papyri had been preserved by the dry sand and were primarily written in Greek, although there were also Latin and later Arabic documents in the mix. The discovery generated immense excitement, with visions of the lost works of antiquity dancing in people’s heads.

Indeed several important ancient literary treasures were discovered among the papyri: large sections of lost Euripides plays plus a biography of him by Satyrus the Peripatetic, an essay by philosopher Empedocles on the anatomy of the eye, the oldest and most complete diagrams from Euclid’s Elements, some never-before-seen letters by Epicurus, seven of the 107 lost books of Livy, and many fragments of the elusive Menander whose comedies were immensely popular in antiquity but barely survived at all.

Scholars also identified a number of theological writings, including gospels canonical and non, and portions of books from the Septuagint, both Hebrew canonical and Apocryhpa, plus all kinds of fragments of quotidian life in Greco-Roman Egypt like receipts, loan notes, work contracts, government edicts.

Scholars also identified a number of theological writings, including gospels canonical and non, and portions of books from the Septuagint, both Hebrew canonical and Apocryhpa, plus all kinds of fragments of quotidian life in Greco-Roman Egypt like receipts, loan notes, work contracts, government edicts.

Still, it’s been over a hundred years since the papyri were discovered and only 15% of them have been identified. For most of that time the process has been scholar-intensive, with each character on each fragment having to be documented by a classicist. The dawn of the computer era allowed for some easier identifications based on comparisons of string of papyrus text with known ancient works, but there is so much volume of data to go through, so many variations in scribe handwriting and so much non-literary material that clunky queries just won’t cut the mustard.

So Oxford University, which owns the bulk of the papyri, and the Egypt Exploration Society enlisted the help of University of Minnesota astrophysicists and papyrologists to devise a crowdsourced solution.

This is where Zooniverse, a collaboration of astrophysicists and public volunteers comes in. The general public will be able to help “read” the texts by locating the placement of ancient Greek letters, and matching the shapes of letters in order to help create strings of letters, which will allow the algorithms to learn to translate and recognize the various characters. Using an interface first developed for the Zooniverse collaboration to allow the general public to identify the shapes of galaxies, volunteers will be able to click on places where they think a letter might be. This data should train the algorithms to improve their ability to translate the texts.

Check it out on the Ancient Lives website. I just did three fragments and it’s easy. Even fun. (I spent many hours of a wayward youth playing Concentration.)

You see a large picture of the fragment and a keyboard of Greek characters beneath. Hover over one of the characters to see an example of it as written in a scribe’s hand over on the right above the accents and symbols. Click on one of the characters on the picture of the papyrus, then click on the corresponding character on the keyboard. Keep doing that until your friends call the cops because they haven’t seen you for days, then click save.

Intriguing! CAPTCHA rules the world! Or else, we are witnessing the ultimate application of the “hundred monkeys at a hundred typewriters writing Hamlet” model. There is a huge attraction these days to the prospect of wikipediaing everything and substituting sheer numbers for expertise (a prospect that scares the hell out of me, truth be told.) ANYWAY, this will be an interesting test case… Some years ago, I took part in various discussions regarding the potential for using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) for transcribing archival documents (sixteenth through eighteenth century, mostly in Italian, from the Medici Granducal Archive here in Florence)and it was not encouraging. Handwritings and spellings were too irregular, too many words were abbreviated, and context was too often essential for identifying words. That is to say, whole words and even clusters of words were the essential constituent elements, not single letters. HOWEVER, these Greek manuscripts from the sands might well represent a different set of variables. And maybe (just maybe) algorithms are getting smarter…???

I’m going to try and help with this project (even if I am only one of a hundred monkeys,Mr. Goldberg…). I have been deeply affected by seeing letters carved into 2000+ year old monuments that I immediately recognized ever since we were stationed at Incirlik AFB in Turkey. We were surrounded by ancient history and many museums,and stone coffins carved with flowers, figures resembling Cupid, letters and sometimes words I could actually read. It sends a chill down your spine, to see not just the carved figure, but the very name of someone long dust.

Hello Just discovered your wonderful History Blog and found the language symbols very interesting, also helpful as I now live in Crete and still struggle with the language.Thanks for sharing. I look forward to your future posts.

This is a really cool project – and I love that the nature of the classics community is really pulling behind it and everyone is chipping in. I think the combined effort from everyone will result in a rate of progress previously unseen in the translating realm. Also, if you love the classics, you might like my site – dedicated to Ancient Greek and latin literature 🙂 http://classicalwisdom.cm