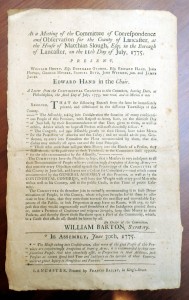

Lehigh University professor Scott Gordon found what he believes to be the only copy left in existence of a Revolutionary War broadside in the Lititz Moravian Church Archives and Museum in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Broadsides were printed posters hung in public places or read aloud to get the word out in the days before mass media.

Lehigh University professor Scott Gordon found what he believes to be the only copy left in existence of a Revolutionary War broadside in the Lititz Moravian Church Archives and Museum in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Broadsides were printed posters hung in public places or read aloud to get the word out in the days before mass media.

This particular one was published on July 11, 1775, by the Committee of Correspondence and Observation for the County of Lancaster on behalf of the Continental Congress. It was an appeal to people who had religious objections to volunteering to taking up arms against the British that they might instead contribute money to the war effort. At least 200 copies were printed, some in English, some in German. According to the Professor Gordon’s extensive research, this is the only surviving English copy, and the only surviving intact copy. The Library of Congress has a fragment of the German version.

There were a great many German immigrants in Lancaster County. The town of Lititz, where the broadside is on display, was founded in the 1740s as a closed Moravian Church community. The Moravian denomination was pacifist (which didn’t stop William Henry, Esq., the first committee member listed on the broadside, from becoming a very successful gunsmith), as were other Christian denominations prevalent among people of German extraction, like the Amish and Anabaptists. The broadside basically goads these conscientious objectors to give money, strongly implying that their pacifism might be seen as a cover for stinginess rather than a dearly held principle.

The Committee do therefore join in earnestly recommending it to such Denominations of People, in this County, whose religious Scruples forbid them to associate or bear Arms, that they contribute towards the necessary and unavoidable Expences of the Public, in such Proportion as may leave no Room, with any, to suspect that they would ungenerously avail themselves of the Indulgence granted them; or, under a Pretence of Conscience and religious Scruples, keep their Money in their Pockets, and thereby throw those Burthens upon a Part of the Community, which, in a Cause that affects all, should be borne by all.

The broadside has been on display at the Lititz Moravian Church museum since at least the 1970s; it’s just that nobody realized it was so rare as to be one-of-a-kind. Dorothy Earhart has been giving tours at the museum since the 1960s and she thinks the paper has probably been kept at the church ever since the minister received it from the committee in 1775. He would have read the German translation aloud to his congregation and passed it around. Earhart thinks that since the German-speaking congregants had little use for the English version, the minister just filed it away and forgot about it.

The message “is of special significance to us as Moravians, as noncombatants,” [Earhart] added. “It’s very special to our community … and it’s kind of neat to have the only surviving copy.”

Moravians supported the Continental Army — “not the war, the army,” Earhart stressed — with food, clothes and medicine. In fact, another document in the showcase is a copy of a letter from Washington to Moravian Bishop John Ettwein regarding a military hospital in Lititz.

The museum will keep the broadside on display. It’s in excellent condition so whatever they’ve been doing for the past 236 years they just need to keep doing.

What a treasure…I greatly enjoyed reading the actual document. The language is so interesting. It would seem William Henry’s behavior would legitimize the broadside’s argument that they were not pacifists at heart. :angry:

I love the elegance of language too, especially considering that these were made for public consumption.

RE: pacifist gunsmiths, forget not that back then, one used a gun to “go shopping” for turkey, deer, and other wild game. Just because they didn’t shoot people doesn’t mean they didn’t shoot animals…

Very true. I would imagine most every household had a weapon for hunting back then.

Thank you for that reminder….but I still see how someone wanting to manipulate the religious pacifists into doing what they wanted them to do, they could point out their ownership of guns as hypocrisy, or as evidence in support of their argument that they are merely being “stingy” and not truly following a “dearly held belief.” But that was a great clarification, thank you!!

Even within the Moravian community there was a lot of debate on the question of whether to enlist. I’m sure outsiders would have no problem pointing to inconsistencies and hypocrisies. William Henry, as it happens, was so successful a gunsmith because he sold weapons to armies and not just the Continental one. He made a killing, if you’ll pardon the pun, selling rifles to the British during the French and Indian War.

Very interesting. I suppose Henry could still justify, or reconcile his pacifist position with his “business deals” as means of survival. 🙂

Or he might have rationalized that as long as he wasn’t shooting, he wasn’t violating any religious precepts. He was very much involved in the Revolution, though, so I suspect he simply had no object to participating in a war he considered just.

Scott Gordon here. Henry had been a riflemaker during the 1750s: rifles weren’t typically used in wartime, since they were very slow to load, etc.; muskets were. So I think Moravian riflemakers believed (and probably rightly so) that they weren’t making weapons of war. During the revolution, Pennsylvania did supply rifle units, which were used in wartime. By this period, though, Henry wasn’t any longer a gunsmith. The Lancaster County committee forced many of Lancaster’s riflemakers to make muskets instead, which they objected to (for a number of reasons): but, threatened with being branded enemies of the state, most complied (including Moravians).

Fascinating. Was the enemy of the state designation something that might have legal repercussions or was it the potential damage to their PR that cowed the Moravian riflemakers? It seems like the latter would be minimized by the prevalence of anti-war sentiment in the community.

Thank you so much for commenting, and congratulations on bringing this document to light. Did you do a little chairdance when you realized it was probably unique?

There’s actually no evidence, btw, that Henry sold rifles to the British during the French and Indian War–though he did repair rifles for Pennsylvania and Virginia troops in 1756 and again in 1758 (these troops were fighting on the British side). Other than this, there is little surviving evidence about his work as a gunsmith. We know who he apprenticed to (a Moravian gunsmith named Matthias Roesser), but that’s about it.

Moravians and pacifism is very complicated. The church didn’t have an absolute pacifist position as Quakers and Mennonites did. What they did have is a strict policy of “non-entanglement” with worldly matters, which would include fighting on any side of a conflict. So, during the Revolution, the church authorities forbade members from taking sides, bearing arms, etc. Many members did, though, even from settlement communities such as Lititz. And in a town like Lancaster, plenty of Moravians enlisted.

The church rebuked Henry for his entanglement in the world and his extensive involvement in public activities; however, because of this involvement and the public offers he held, he was able to protect the church when it was truly vulnerable. Whether the church saw the contradiction here … hard to say.

Sorry for the double post there. :no:

Yeah, if they had been branded enemies of the state they would have been exiled from PA, lost their property, etc.

Actually, this is what the Moravians faced, too, since in 1777 PA passed two laws–one of which required all adult males to associate in militias, the other of which required them to swear loyalty to the state. The consequences for not complying was, at first, fines and, later, loss of property: unscrupulous neighbors tried to use these laws to strip the various Moravian communities of all they had. (This is when Henry was able to help.)

Lancaster generally was pretty “tolerant” of those who wouldn’t bear arms; these mostly German religious groups had been good citizens for 50 years. But they were pretty harsh toward those who they suspected of being loyalists. The trick was to find a way to distinguish between those who wouldn’t join a militia from religious principles and those who wouldn’t do so because they were opposed to the patriot cause. I guess the broadside–by asking those who wouldn’t bear arms to contribute in other ways–was trying to establish a criterion by which one could tell the difference.