The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet is awarding the Nobel Prizes this week. Yesterday the prize for Medicine went jointly to John B. Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka for their discoveries, Gurdon’s in 1962, Yamanaka’s in 2006, that mature cells dedicated to one specific tissue can be reprogrammed into unspecialized stem cells. This morning the winners of the Physics Prize were announced (Serge Haroche and David J. Wineland “for ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual quantum systems”), followed by Chemistry on the 10th, Literature on the 11th, Peace on the 12th and Economics on the 15th. You can watch live webcasts of the announcements on the Nobel Prize website, assuming it doesn’t crash from the traffic like it did for me.

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet is awarding the Nobel Prizes this week. Yesterday the prize for Medicine went jointly to John B. Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka for their discoveries, Gurdon’s in 1962, Yamanaka’s in 2006, that mature cells dedicated to one specific tissue can be reprogrammed into unspecialized stem cells. This morning the winners of the Physics Prize were announced (Serge Haroche and David J. Wineland “for ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual quantum systems”), followed by Chemistry on the 10th, Literature on the 11th, Peace on the 12th and Economics on the 15th. You can watch live webcasts of the announcements on the Nobel Prize website, assuming it doesn’t crash from the traffic like it did for me.

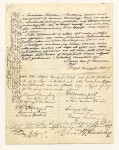

It’s widely known that the Nobel Prizes were founded by wealthy Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, inventor of dynamite. He stipulated in his 1895 will that the bulk of his fortune (31.5 million Swedish kronor then, about 1.5 billion kronor today or $225 million) be invested in “safe securities” and the interest on the fund given away annually as prizes

to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind. The said interest shall be divided into five equal parts, which shall be apportioned as follows: one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field of physics; one part to the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement; one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine; one part to the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction; and one part to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.

An erroneous report of his death seven years earlier may have set him on this course. His brother Ludvig, an innovator in oil production and distribution with some extraordinarily progressive labor views, died of a cardiac condition in Cannes in 1888. Alfred and Ludvig had had an ugly falling out over money years before but were reconciled shortly before his death and Alfred was by his side in Cannes when he died. As the story goes, a French newspaper mistook Ludvig for Alfred and published an obituary entitled “The merchant of death is dead.” The lede was no less hard-hitting: “Dr. Alfred Nobel, who made his fortune by finding a way to kill the most people as ever before in the shortest time possible, died yesterday.”

An erroneous report of his death seven years earlier may have set him on this course. His brother Ludvig, an innovator in oil production and distribution with some extraordinarily progressive labor views, died of a cardiac condition in Cannes in 1888. Alfred and Ludvig had had an ugly falling out over money years before but were reconciled shortly before his death and Alfred was by his side in Cannes when he died. As the story goes, a French newspaper mistook Ludvig for Alfred and published an obituary entitled “The merchant of death is dead.” The lede was no less hard-hitting: “Dr. Alfred Nobel, who made his fortune by finding a way to kill the most people as ever before in the shortest time possible, died yesterday.”

I can’t confirm that this story is true, however. There is no reference I was able to find to the actual newspaper in question, and at least one biographer was unable to find any such mistaken obituary in any French newspaper of the time. The Encyclopaedia Britannica includes the obituary story as factual but notes that there’s no evidence it played a part in Nobel’s thought process. The Nobel Foundation doesn’t mention the obituary story at all.

According to the Foundation, Nobel developed the prize idea gradually over the years, inspired by his own varied interests. An excellent student, he was fluent in six languages, adept at chemistry and a lover of literature, especially the Romantic poets Byron and Shelley. He wrote poetry and a scandalous play that was almost entirely destroyed but recently rediscovered, even for a short while considering a career as a writer. He went with his strengths in the sciences instead, by all accounts a wise choice, and in the end secured 350 patents in various countries to inventions ranging from the dynamite to artificial silk. He also had an interest in medicine, founding a medical lab to research blood and transfusions.

According to the Foundation, Nobel developed the prize idea gradually over the years, inspired by his own varied interests. An excellent student, he was fluent in six languages, adept at chemistry and a lover of literature, especially the Romantic poets Byron and Shelley. He wrote poetry and a scandalous play that was almost entirely destroyed but recently rediscovered, even for a short while considering a career as a writer. He went with his strengths in the sciences instead, by all accounts a wise choice, and in the end secured 350 patents in various countries to inventions ranging from the dynamite to artificial silk. He also had an interest in medicine, founding a medical lab to research blood and transfusions.

Although it’s often said that Alfred Nobel invented dynamite for industrial applications and was horrified to see it used as a weapon of war, by the last decade of his life, he had turned increasingly to the production of arms and munitions. His AB Bofors company in Sweden was a weapons manufacturing concern where his innovations in artillery and war material were produced.

At the same time, he carried on an avid correspondence with Austrian pacifist Bertha von Suttner whom he had met in Paris in 1876 when he hired her as his secretary. She left the job after one week to run off to Vienna and marry her lover, Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner, in secret without the approval of his family. Bertha von Suttner would become famous in 1889 with the publication of her anti-war novel Lay Down Your Arms, a polemical melodrama that popularized the peace movement much like Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for the abolition of slavery.

At the same time, he carried on an avid correspondence with Austrian pacifist Bertha von Suttner whom he had met in Paris in 1876 when he hired her as his secretary. She left the job after one week to run off to Vienna and marry her lover, Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner, in secret without the approval of his family. Bertha von Suttner would become famous in 1889 with the publication of her anti-war novel Lay Down Your Arms, a polemical melodrama that popularized the peace movement much like Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for the abolition of slavery.

Bertha and Alfred often discussed war and peace in their correspondence. In an 1891 letter he told her “Perhaps my factories will put an end to war sooner than your congresses: on the day that two army corps can mutually annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will surely recoil with horror and disband their troops.” We all know how that panned out. Bertha would become one of the earliest recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize, receiving it in 1905.

In November of 1895, Alfred Nobel composed his last will and testament. It was his third iteration. He had changed the wording of the major bequest twice before, finally sticking with this last one. He did not employ a lawyer, a decision that would cause considerable headaches in the implementation of his wishes after his death. He left some moneys to his nieces and nephews, employees, a guy in Texas I was unable to find out anything about, then 94% of his fortune to the prize foundation. As executors he appointed his personal assistant, chemical engineer Ragnar Sohlman, and Rudolf Lilljequist, a civil engineer who had started an electrochemical business with Nobel’s support.

In November of 1895, Alfred Nobel composed his last will and testament. It was his third iteration. He had changed the wording of the major bequest twice before, finally sticking with this last one. He did not employ a lawyer, a decision that would cause considerable headaches in the implementation of his wishes after his death. He left some moneys to his nieces and nephews, employees, a guy in Texas I was unable to find out anything about, then 94% of his fortune to the prize foundation. As executors he appointed his personal assistant, chemical engineer Ragnar Sohlman, and Rudolf Lilljequist, a civil engineer who had started an electrochemical business with Nobel’s support.

Alfred Nobel died in his villa at San Remo, Italy, on December 10, 1896, from a cerebral hemorrhage. When his will was read, it shocked his family and the world. Giant bequests for the advancement of science, literature and peace were not exactly common. The international press was positive, especially since Nobel had made a point of saying the awards should be made without considering country of origin. Initial reactions in the Swedish press were positive too, but King Oscar II was horrified. He saw the will as unpatriotic, as bypassing Swedish interests, and the Peace Prize in particular as a major political hornet’s nest since it was to be awarded by the Norwegian parliament while Sweden and Norway were in the process of getting a national divorce.

His relatives expected a more traditional approach to his legacy. They resented getting peanuts while random writers and lab rats got the bulk. From a business perspective, there were grave concerns that in order to go through with this crazy prize scheme, they’d be forced to sell Alfred’s stock in Branobel, his brothers’ hugely oil company in Russia, to outsiders. Not only would this introduce non-family into the ruling structure of the business, but the mass stock sale could depress the company’s worth and ruin its finances. The heirs of Alfred’s brother Robert’s filed suit to contest the will. Robert’s son Ludvig initiated sequestration procedures against Alfred’s properties.

His relatives expected a more traditional approach to his legacy. They resented getting peanuts while random writers and lab rats got the bulk. From a business perspective, there were grave concerns that in order to go through with this crazy prize scheme, they’d be forced to sell Alfred’s stock in Branobel, his brothers’ hugely oil company in Russia, to outsiders. Not only would this introduce non-family into the ruling structure of the business, but the mass stock sale could depress the company’s worth and ruin its finances. The heirs of Alfred’s brother Robert’s filed suit to contest the will. Robert’s son Ludvig initiated sequestration procedures against Alfred’s properties.

The academies Nobel had named as awarding bodies were also not too thrilled. The will was vague on details, with little information on how the prizes were to be awarded. With so many influential people dead set against the scheme and the will in legal limbo, the Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Caroline Institute in Stockholm and the Academy in Stockholm hesitated for years before accepting their duties.

Then there were the tax issues, primarily in France which considered Nobel a resident even though he had homes all over Europe and had died in Italy. Ragnar Sohlman had to pull some serious cloak-and-dagger to get Nobel’s stocks and financial papers out of various French banks and into safe hands in Sweden. That wasn’t the only giant pain Sohlman had to suffer to fulfill Alfred’s last wishes. He co-executor was too busy running his factory to be fully involved, so he just acted in an advisory capacity. It was Sohlman who fought the governments of France, Sweden and Norway, the prize-giving institutions and the Nobels themselves non-stop for five years to make it all happen.

Then there were the tax issues, primarily in France which considered Nobel a resident even though he had homes all over Europe and had died in Italy. Ragnar Sohlman had to pull some serious cloak-and-dagger to get Nobel’s stocks and financial papers out of various French banks and into safe hands in Sweden. That wasn’t the only giant pain Sohlman had to suffer to fulfill Alfred’s last wishes. He co-executor was too busy running his factory to be fully involved, so he just acted in an advisory capacity. It was Sohlman who fought the governments of France, Sweden and Norway, the prize-giving institutions and the Nobels themselves non-stop for five years to make it all happen.

Finally the family was appeased with the help of Emanuel, the son of Alfred’s brother Ludvig of fake obituary fame. He didn’t want to contest the foundation; he just wanted to ensure the shares of Branobel stayed in the family. King Oscar II himself tried to browbeat him into breaking the will, summoning him to an audience and lecturing him on the problems the Peace Prize would cause. Emanuel stood firm, even shoring up Sohlman’s spirits when they flagged, telling him that the word for executor in Russian means “vicar of the soul.”

Emanuel helped broker amendments to the will to satisfy his cousins. In addition to the modest bequests of a few hundred thousand kronor, they would receive 1,000,000 kronor more. The Nobel heirs would also be involved in the development of the statutes common to all awarding bodies, so they’d have a say in the standards and execution of the prizes. Emanuel also raised money to buy out his uncle’s stock himself to keep it all in the family.

Emanuel helped broker amendments to the will to satisfy his cousins. In addition to the modest bequests of a few hundred thousand kronor, they would receive 1,000,000 kronor more. The Nobel heirs would also be involved in the development of the statutes common to all awarding bodies, so they’d have a say in the standards and execution of the prizes. Emanuel also raised money to buy out his uncle’s stock himself to keep it all in the family.

The remaining issues were resolved when Sohlman enlisted the aid of an actual lawyer. The new legal adviser wrote to Swedish attorney general asking him to weigh in on the case, and the AG came down on their side saying that even though no direct interests of the crown were involved, it was right that the government “assist in putting the testator’s wishes into effect.” With that decision on their side, King Oscar II went off to suck an egg and all the prize-awarding bodies accepted their duties by late 1898.

The government formally endorsed the creation of the Nobel Foundation on September 9th, 1899. One more year was spent in negotiations between the awarding institutions and the Nobel family over the statutes of the Foundation. On June 29th, 1900 a royal ordinance established the statutes of the Nobel Foundation and special regulations governing all the Swedish prize-giving committees. On December 10th, 1901, the first Nobel Prizes were awarded in Stockholm and Oslo.

Good a time as any to bring up the question of why there is no Nobel Prize for mathematics. The favorite line is that a mathematician made off with Alfred’s wife or girlfriend, take your pick. Other explanations are more mundane and discussed here.

I wonder how Alfred Nobel would feel about the peace prize going to the EU this year?

Alfred Nobel was a great man.

Fitting, that the Nobel prizes, honoring man’s greatest achievements on a yearly basis, would go into effect at the turn of the bloodiest, most horrific, centuries in human history. Also, the century that has produced the greatest works of art, the loudest calls for social justice, the invention of the digital computer, and landing a man on the moon. Essentially, on the cusp of the most event-filled century ever.

:crbemas nochjrs. salido sl comitr nonrl lsuradosnominados rnhorsbuena galardonados docoemntes ptofedored alumna,do que tengsngsid felices suenos reposo tranquilidad armonia distincion.y: