It all started with an exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Art. I’ve mentioned before that I am an avid lover and collector of postcards, so whenever a museum puts on a show of vintage postcards, I go full obsessive and try to hunt down as many pictures of it as humanly possible. The Postcard Age at the MFA looks like a particularly great display of hundreds of carefully selected gems from the massive collection of Leonard A. Lauder, the billionaire chairman emeritus of Estée Lauder Companies, Inc., and son of legendary cosmetics entrepreneur Estée.

It all started with an exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Art. I’ve mentioned before that I am an avid lover and collector of postcards, so whenever a museum puts on a show of vintage postcards, I go full obsessive and try to hunt down as many pictures of it as humanly possible. The Postcard Age at the MFA looks like a particularly great display of hundreds of carefully selected gems from the massive collection of Leonard A. Lauder, the billionaire chairman emeritus of Estée Lauder Companies, Inc., and son of legendary cosmetics entrepreneur Estée.

Lauder has been collecting postcards since he was six years old when he fell in love with an Art Deco postcard of the Empire State Building. It cost a penny. He spent his entire nickel allowance buying five of those postcards. Thus began a love affair that continues to this day. His collection of cubist masterpieces is worth hundreds of millions of dollars and known worldwide, but it was the humble postcard that made a collector out of him. His postcard collection today numbers around 125,000 pieces, and that’s after he donated 20,000 early 20th century Japanese postcards to the MFA some years ago.

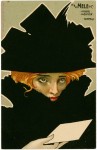

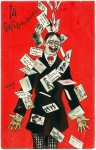

He has pledged to donate another 100,000 to the museum. Out of that hundred thousand, Lauder and MFA curators Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss selected almost 700 postcards from the decades around the turn of the 20th century to put on display in The Postcard Age. This was the time when picture postcards, first sold in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1869, became all the rage. By 1900, billions of postcards of advertising graphics, travel photographs, famous people, famous buildings, sports events, conventions, World’s Fairs, the latest technology, were sent all over the world. At a penny per stamp, they were cheaper than phone calls, fast and pretty. They were also purchased and kept in scrapbooks. In an era before cameras were readily available and easy to use, you could document your trip to exotic locales with postcards.

He has pledged to donate another 100,000 to the museum. Out of that hundred thousand, Lauder and MFA curators Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss selected almost 700 postcards from the decades around the turn of the 20th century to put on display in The Postcard Age. This was the time when picture postcards, first sold in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1869, became all the rage. By 1900, billions of postcards of advertising graphics, travel photographs, famous people, famous buildings, sports events, conventions, World’s Fairs, the latest technology, were sent all over the world. At a penny per stamp, they were cheaper than phone calls, fast and pretty. They were also purchased and kept in scrapbooks. In an era before cameras were readily available and easy to use, you could document your trip to exotic locales with postcards.

The postcard craze was such a huge thing that there are even postcards about postcards, some advertising postcards as a means to stay in touch with friends, others dedicated to the worldwide phenomenon of the postcard craze itself. You can see some of the highlights of the exhibit in this MFA slideshow and in this one on the Huffington Post. Imprint has some superb pictures from the exhibit accompanying this article about the exhibit that also includes a fascinating interview about the history of postcards with pop culture historian and graphic designer Jim Heimann. A book of the exhibition with many more pictures is available here.

The postcard craze was such a huge thing that there are even postcards about postcards, some advertising postcards as a means to stay in touch with friends, others dedicated to the worldwide phenomenon of the postcard craze itself. You can see some of the highlights of the exhibit in this MFA slideshow and in this one on the Huffington Post. Imprint has some superb pictures from the exhibit accompanying this article about the exhibit that also includes a fascinating interview about the history of postcards with pop culture historian and graphic designer Jim Heimann. A book of the exhibition with many more pictures is available here.

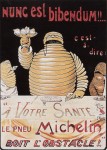

One postcard in the slideshows particularly caught my eye. It’s a photograph of two enormous Michelin Men riding a horse-drawn cart through the streets of Houston, Texas, around 1904. The Michelin Man was just six years old in 1904. The idea of an anthropomorphic tire pile came to Edouard and André Michelin in 1894 and when in 1898 the French cartoonist Marius Rossillon, aka O’Galop, showed André an image he had drawn for a brewery of a Falstaffian figure toasting “Nunc est bibendum” (“Now is the time to drink,” a quote from one of Horace’s odes), Michelin suggested the figure be made to resemble a human tire pile. The first Michelin Man thus became known as Bibendum after the slogan. It’s that early character with his pince-nez glasses you see advertising Michelin tires in person in Houston.

One postcard in the slideshows particularly caught my eye. It’s a photograph of two enormous Michelin Men riding a horse-drawn cart through the streets of Houston, Texas, around 1904. The Michelin Man was just six years old in 1904. The idea of an anthropomorphic tire pile came to Edouard and André Michelin in 1894 and when in 1898 the French cartoonist Marius Rossillon, aka O’Galop, showed André an image he had drawn for a brewery of a Falstaffian figure toasting “Nunc est bibendum” (“Now is the time to drink,” a quote from one of Horace’s odes), Michelin suggested the figure be made to resemble a human tire pile. The first Michelin Man thus became known as Bibendum after the slogan. It’s that early character with his pince-nez glasses you see advertising Michelin tires in person in Houston.

His creation of one of the world’s most enduring and recognizable trademarks is what O’Galop is mostly known for today, but what I just found out while obsessing over that picture is that O’Galop was also a pioneer of film animation. Starting in 1910, he and biologist Dr. Jean Comandon, a pioneer in his own right of slow motion and microcinematography (filming through a microscope), worked together to create films on good hygiene and disease prevention. A disturbingly awesome example of their oeuvre is On Doit Le Dire, a 1918 short about the dangers of syphilis which combines animation, pictures of real people’s syphilis lesions and film of spirochetes under the microscope.

His creation of one of the world’s most enduring and recognizable trademarks is what O’Galop is mostly known for today, but what I just found out while obsessing over that picture is that O’Galop was also a pioneer of film animation. Starting in 1910, he and biologist Dr. Jean Comandon, a pioneer in his own right of slow motion and microcinematography (filming through a microscope), worked together to create films on good hygiene and disease prevention. A disturbingly awesome example of their oeuvre is On Doit Le Dire, a 1918 short about the dangers of syphilis which combines animation, pictures of real people’s syphilis lesions and film of spirochetes under the microscope.

O’Galop also lent his animation talents to the Commission for the Prevention of Tuberculosis in France, an agency of the Rockefeller Foundation which worked closely with French national and regional governments and the Red Cross to reduce the rates of tuberculosis which had been driven sky-high by the deprivations of World War I. Precise mortality statistics are hard to come by during wartime, but we do know that 291,412 people died of tuberculosis between 1915 and 1918 in 77 of France’s 87 departments. The proportion of deaths was higher in occupied areas.

The Rockefeller Foundation had been involved in disease prevention, primarily the eradication of hookworm disease, for many years. In 1917, it created the Commission to combat the increase of tuberculosis in France. The Commission took a comprehensive approach to the fight against TB, starting with the collection of reliable statistics to define the extent and range of the problem, then establishing a system of anti-tuberculosis dispensaries, clinics all over the country with modern equipment and highly trained staff to treat tuberculosis cases. Each dispensary had a thoroughly equipped mobile dispensary that would bring a doctor and assistants to centrally located villages where all applicants would be tested, diagnosed and treated. It also trained nurses who headquartered in the dispensaries and did house calls to test and treat. Because of their peripatetic duties, the nurses, all women, were called Visiteuses d’Hygiene (visiting hygiene ladies).

The Rockefeller Foundation had been involved in disease prevention, primarily the eradication of hookworm disease, for many years. In 1917, it created the Commission to combat the increase of tuberculosis in France. The Commission took a comprehensive approach to the fight against TB, starting with the collection of reliable statistics to define the extent and range of the problem, then establishing a system of anti-tuberculosis dispensaries, clinics all over the country with modern equipment and highly trained staff to treat tuberculosis cases. Each dispensary had a thoroughly equipped mobile dispensary that would bring a doctor and assistants to centrally located villages where all applicants would be tested, diagnosed and treated. It also trained nurses who headquartered in the dispensaries and did house calls to test and treat. Because of their peripatetic duties, the nurses, all women, were called Visiteuses d’Hygiene (visiting hygiene ladies).

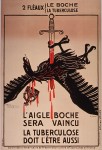

A public education campaign was the fourth prong of the Commission’s efforts. During the war, striking propaganda posters defined tuberculosis as an enemy to be battled just like Germany out of patriotism. There were also educational posters which used simple cartoons and drawings to explain how to prevent tuberculosis (sleep with windows open, no public spitting or sharing bottles) and if you have it, how to keep from spreading it (sleep alone, spit into containers and destroy the contents).

A public education campaign was the fourth prong of the Commission’s efforts. During the war, striking propaganda posters defined tuberculosis as an enemy to be battled just like Germany out of patriotism. There were also educational posters which used simple cartoons and drawings to explain how to prevent tuberculosis (sleep with windows open, no public spitting or sharing bottles) and if you have it, how to keep from spreading it (sleep alone, spit into containers and destroy the contents).

The education campaign also had a traveling component. The Mobile Tuberculosis Exhibit, a truck filled with pamphlets and posters that could be set up in a public space, 42 films and a projector, drove around the country to spread the word on stopping the spread of TB. Many of these exhibitions were targeted towards children for whom O’Galop’s animated films were a major draw. The were cartoons, but they certainly didn’t treat the subject gingerly.

The education campaign also had a traveling component. The Mobile Tuberculosis Exhibit, a truck filled with pamphlets and posters that could be set up in a public space, 42 films and a projector, drove around the country to spread the word on stopping the spread of TB. Many of these exhibitions were targeted towards children for whom O’Galop’s animated films were a major draw. The were cartoons, but they certainly didn’t treat the subject gingerly.

They also didn’t just stick to TB. Medical opinion at the turn of century asserted that alcoholism, both acquired and hereditary, was a major cause of TB. Thus the fight against tuberculosis also required a fight against alcoholism — and not just alcoholism as we define it now; even one spiritous beverage a day was alcoholism for their purposes.

They also didn’t just stick to TB. Medical opinion at the turn of century asserted that alcoholism, both acquired and hereditary, was a major cause of TB. Thus the fight against tuberculosis also required a fight against alcoholism — and not just alcoholism as we define it now; even one spiritous beverage a day was alcoholism for their purposes.

Hence the following triad of O’Galop films: Small Causes, Big Effects, Resisting Tuberculosis and The Alcohol Cycle. (You can watch a version subtitled in your choice of English, Italian, German and Spanish on the excellent Europa Film Treasures website.) Resisting Tuberculosis is my favorite. It starts at 1:50 and features some outstanding animated skeleton work.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/fuk7d1pnvK4&w=430]

I like that the healthy non-drinker in the Evils of Alcohol cartoon has a serious beer belly while the topers all appear to have what we would consider a desirable BMI.

Yeah, he is not exactly what we would consider the athletic paragon of good health these days. I suspect after the privations of war, having a big ol’ gut was an indicator that you ingested actual nutrients on a regular basis, whereas thin equaled malnourished.

Hi there! Someone in my Facebook group shared this website with us so I

came to give it a look. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers!

Outstanding blog and excellent design and style.