While frolicking through silent movie history yesterday, I came across a veritable treasure of a comedic short. It’s called The Mystery of the Leaping Fish and it stars Douglas Fairbanks as Coke Ennyday the “scientific detective,” a parody of Sherlock Holmes who was a cocaine aficionado albeit nowhere near as rabid a one as Mr. Ennyday. The character’s name isn’t the only shameless, even joyful, drug reference. Our hero is not only an avowed drug user, he wears a bandolier of syringes filled with liquid cocaine strapped to his chest and injects himself every few minutes. He also has a large round box labelled “COCAINE” in large print that he grabs fistfuls of powder out of that he then buries his face into with Scarface-like gusto. His wall clock eschews hour markers in favor of four words at the cardinal points: eats, sleep, drinks, dope. When the single hand points to drinks, Ennyday’s manservant makes him the beverage of champions: equal parts Gordon’s Gin, laudanum and prussic acid (a solution of hydrogen cyanide).

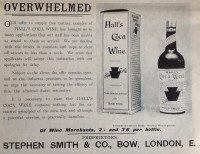

This is no Reefer Madness. There is no stern moral conclusion about the evils of drugs. Fairbanks is his usual gregarious, athletic self, just sillier than usual. This was filmed in 1916 when drugs like cocaine, cannabis and opiates were readily available from pharmaceutical companies. Many states had laws against the sale and use of coca and opium and in December of 1914 Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act which in theory made it a federal crime. Authorized companies (pharma) and individuals (doctors, patients) could still dispense and use cocaine and opiates, however.

This is no Reefer Madness. There is no stern moral conclusion about the evils of drugs. Fairbanks is his usual gregarious, athletic self, just sillier than usual. This was filmed in 1916 when drugs like cocaine, cannabis and opiates were readily available from pharmaceutical companies. Many states had laws against the sale and use of coca and opium and in December of 1914 Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act which in theory made it a federal crime. Authorized companies (pharma) and individuals (doctors, patients) could still dispense and use cocaine and opiates, however.

Douglas was still a comparative rookie when he made this wacky picture, having moved to Hollywood in 1915 and signed a contract with the newly formed Triangle Pictures where he worked under the D.W. Griffith point of the triangle (the other two points were Thomas Ince and Mack Sennet). His first film was released in November 1915. The Mystery of the Leaping Fish was released just seven months later in June of 1916. By then, with fewer than 10 films under his belt, he already had above the title billing. It was the second time he worked with husband and wife writing team John Emerson and Anita Loos. Emerson directed the picture — very amusingly, I might add; there are some great comedic beats in there — and Loos wrote the intertitles with tongue firmly in cheek. Fairbanks made his own contributions to the script, something you see reflected in the beginning and closing sequences where he’s playing himself pitching the madcap story of Coke Ennyday to a studio writer who naturally tells him this is a ridiculous idea for a picture that will never be made.

(Loos would later go on to write the novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, a huge success in print, on stage and in film, with the most famous movie version starring Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell. Emerson would go on to be a huge parasite on his wife, sponging off her success, stealing her money, losing it all and stealing it again when she bounced back, all the while cheating on her and manipulating her with faked illnesses and endless drama.)

When Fairbanks rose to the loftiest heights of Hollywood fame, he reportedly came to hate this wild foray into drugged-out good times and tried to have it destroyed. With all the silent pictures we’ve lost to time and nitrate volatility and studios not giving a crap about their history, it’s remarkable that this bizarre little two-reeler survived even when the greatest star of the era wanted it gone.

When Fairbanks rose to the loftiest heights of Hollywood fame, he reportedly came to hate this wild foray into drugged-out good times and tried to have it destroyed. With all the silent pictures we’ve lost to time and nitrate volatility and studios not giving a crap about their history, it’s remarkable that this bizarre little two-reeler survived even when the greatest star of the era wanted it gone.

Also of historical note is the relatively subdued racist angle. There’s a Chinese laundry guy/opium dealer stereotype, but it’s small potatoes compared to the blatant racism of the debate around the passage of the Harrison Act which was all about cocaine making black men crazy, aggressive, superstrong and driving them to rape white women, while the Chinese used opium to lure innocent white girls into drug addiction, illicit relationships and, inevitably, prostitution.

The movie really doesn’t care about any of that noise. It’s quite remarkable, because studios were consistently cowardly when it came to potentially controversial issues, even before the Fatty Arbuckle scandal and the later implementation of the Production Code. The story was by Tod Browning, best known today for his ground-breaking and still creepy as hell talkie Freaks. He had run away from home to join the circus when he was a teenager, so he was not easily scandalized.

Anyway, without further ado, here is The Mystery of the Leaping Fish.

Holy moley, what a bizarre little movie! Ha!

Isn’t it just? I’d only seen Fairbanks in his famous swashbuckling roles before I stumbled on this treasure. I’m so glad it survived against all odds.

This is something. I did love the car horn.

That whole car is the best. I love it when they whip out the checkers set.

Ironic trivia: Fairbanks’ 19-year-old co-star, Alma Rubens, later struggled with drug addiction which contributed to her death from pneumonia in 1931.

1916 was her breakout year — in addition to The Mystery of the Leaping Fish she made six other films. The following year she appeared in EIGHT.

Within a few years, however, she became hooked on drugs as a result (she later claimed) of a painful “womanly weakness” (most likely endometriosis) — rather than perform a hysterectomy on such a young woman, her gynecologist chose the only other treatment available at the time: he shot her up with morphine.

In a scathingly self-revealing autobiography, This Bright World Again, completed only a month before her death, Rubens graphically described her long, slow decline from $3000-a-week movie star to desperate addict eagerly trading a $4,000 mink coat for just a few days worth of drugs.

Along the way were Hollywood drug-and-sex parties, three brief marriages (two to spouse abusers), a string of violent episodes and multiple failed attempts at sobriety (“You’re both fools,” she declared to her mother and husband immediately after one release. “I’m still an addict. And now I’m going straight to hell.”)

In February of 1929, after stabbing a sanitarium nurse with a pen knife and running down Hollywood Boulevard screaming for help, Rubens’ addiction became front page news. It would remain so for the last two years of her life — as, for example, in this article from the Pittsburg Press of May 7, 1928, headlined “Film Star Goes to Insane Ward for Drug Cure” which describes other psychotic episodes and hospital stays:

http://tinyurl.com/koar7uo

In early January 1931, she was arrested in San Diego for attempting to smuggle 100 grains of morphine sewn into the lining of an evening gown. Three weeks later, she was dead at just 33.

The final line of her autobiography could be every addict’s epitaph: “God pity me, God forgive me, and God help all poor mortals who fall into the clutches of the monster — dope.”

Alma Rubens in better days:

http://tinyurl.com/nqbrxda

And (pardon the picture quality) at the end:

http://tinyurl.com/ks43dvb

I knew she had died young after years of drug abuse, but I had no idea her fall was so dramatic and public. The fact that it started with morphine shots reminds me of the tragic death of Wallace Reid who was to all intents and purposes murdered by his studio (Famous Players-Lasky, the future Paramount Pictures). They shot him full of morphine when he was injured on set and then drove him to keep making so many pictures so quickly that he never had a chance to recover. By the end they had a doctor on set to administer morphine shots every 15 minutes just so he could put one foot in front of the other. He died at 31 years of age while detoxing at a sanitarium.

I am using Yosemite on a recent Mac. I have updated Java to the latest as per Apple’s Java Update site. Yet, when I try to play the video I am told my Java is out of date. It asks me to update it through the video. I say yes. Nothing happens.

If WikiMedia wants Mac users to view their videos, they had better provide a way.

That’s so frustrating. I almost used the YouTube version, but the picture quality is distinctly inferior. Sorry to have inflicted that Java nonsense on you.

Found it at YouTube. No damn java required.

too wonderful!

Agreed!

Just wanted to note that the Coke Enneday character was really more of a cross between Sherlock Holmes and Craig Kennedy, Scientific Detective. Besides riffing off the name, Coke is referred to as a scientific detective, just as Craig Kennedy was. But as far as I know, Craig Kennedy didn’t use drugs, thus, the Holmes connection.

Craig Kennedy, sometimes touted as the American Sherlock Holmes, was a detective created by the writer Arthur B. Reeve and first appeared in print in 1910. Several early Craig Kennedy books are in the public domain and are available on Project Gutenberg (among other places).

They had all those sex and drug parties, and didn’t invite me. Sigh.