Last night Turner Classic Movies aired the restored work print of Orson Welles’ Too Much Johnson found in Pordenone, Italy, in 2008. It was the second film Welles ever made (the first was a short eight minutes long; the third was Citizen Kane) and had long been thought lost before the silent film experts of Cinemazero discovered the print that had been languishing forgotten in a shipping company warehouse since the 70s.

An adaptation of an 1894 play by William Gillette, Welles made significant changes to the original script of Too Much Johnson for an experimental staging by his Mercury Theatre company. The original plan was for the three reels of the picture to be introductions to each act, the first reel 20 minutes long, the remaining two 10 minutes each. The film was silent slapstick in the style of Mack Sennett’s early comedies and it would set the stage for a performance of the play done as a screwball comedy.

An adaptation of an 1894 play by William Gillette, Welles made significant changes to the original script of Too Much Johnson for an experimental staging by his Mercury Theatre company. The original plan was for the three reels of the picture to be introductions to each act, the first reel 20 minutes long, the remaining two 10 minutes each. The film was silent slapstick in the style of Mack Sennett’s early comedies and it would set the stage for a performance of the play done as a screwball comedy.

This was Welles’ first full experience of shooting and editing a movie. In 10 days of filming, he shot 25,000 feet of film. He took all 25,000 feet of highly flammable 35mm nitrate to his hotel suite at the St. Regius and edited it himself on a Moviola machine. Producer John Houseman and assistant director John Berry aided him in this slightly insane endeavor, and would later recall that nitrate film covered the floor of the suite reaching knee-high. There was at least one fire. Somehow, the men, the film, the hotel suite and the hotel, for that matter, survived this cockamamie scheme, and Welles managed to narrow down the 10 reels of footage to a rough working print just over an hour in running time.

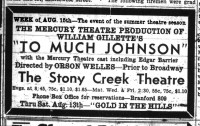

He never did finish editing the movie. There may have been an issue with royalties — Paramount owned the film rights to the original play — and legend has it the Stony Creek Theatre, the theater near New Haven where the play was to have its trial run, did not have the fireproof projection booth and/or a high enough ceiling to show the film. However, Paramount has no record of sending Welles a letter asserting their rights and the Stony Creek Theatre started out as the Lyric Theater, a nickelodeon, in 1903 (the same year The Great Train Robbery altered the movie-going landscape forever) so even though it was purchased by a community theater group in 1920 and a proper stage and fly gallery added, it seems odd that it would have lost all its original film projection capabilities by August 16th, 1938, when the Too Much Johnson preview began.

Whatever the reason, the movie part of the Mercury staging of the play never did happen. Without it the play, which Welles had modified extensively assuming there would be introductory films, didn’t work and the New Haven trial was a flop. Although Welles made noises that the play would move on to Broadway, the debut kept getting postponed and ultimately dropped. The Mercury Theatre company had begun putting on live hour-long radio dramas in July of 1938, and in October of that year they pulled off the greatest radio drama caper of all time with the broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. The huge reaction got them a sponsor (Campbell’s Soup) and two more years of weekly shows, so Too Much Johnson fell by the wayside.

Whatever the reason, the movie part of the Mercury staging of the play never did happen. Without it the play, which Welles had modified extensively assuming there would be introductory films, didn’t work and the New Haven trial was a flop. Although Welles made noises that the play would move on to Broadway, the debut kept getting postponed and ultimately dropped. The Mercury Theatre company had begun putting on live hour-long radio dramas in July of 1938, and in October of that year they pulled off the greatest radio drama caper of all time with the broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. The huge reaction got them a sponsor (Campbell’s Soup) and two more years of weekly shows, so Too Much Johnson fell by the wayside.

The footage wound up in storage. Welles himself completely forgot about it until he found a print at his house in Madrid in the 1960s. He refused to show it publicly, saying that it made no sense without the play context, much like the play had made little sense without the companion film. When that print was lost in a fire, scholars thought this important transitional piece that had much to reveal about the development of Welles’ directorial approach was gone forever. That’s why the discovery of the second print in Pordenone was greeted with such joy by film nerds and Welles’ fans.

Too Much Johnson was restored by the geniuses at the George Eastman House with invaluable help from Haghefilm Digitaal in the Netherlands and had its world debut at a silent film festival in Pordenone in October of 2013 before making its US debut later that month at the George Eastman House. That viewing was for members only; the rest of us had to wait to get our eyeballs on it, so I was kicking myself for not realizing ahead of time that the movie would finally air on a widely accessible cable channel. It’s pretty great, too. I didn’t find it all that confusing, even though there are no intertitles and there are repetitive takes included.

Too Much Johnson was restored by the geniuses at the George Eastman House with invaluable help from Haghefilm Digitaal in the Netherlands and had its world debut at a silent film festival in Pordenone in October of 2013 before making its US debut later that month at the George Eastman House. That viewing was for members only; the rest of us had to wait to get our eyeballs on it, so I was kicking myself for not realizing ahead of time that the movie would finally air on a widely accessible cable channel. It’s pretty great, too. I didn’t find it all that confusing, even though there are no intertitles and there are repetitive takes included.

The stand-outs for me are Joseph Cotten, who legs it over the rooftops of New York City with impressive gameness, grace and skill, the cinematography and the angled shots, surprising quick-cuts and close-ups that would come to define the Welles of Citizen Kane and after. Cotten makes Harold Lloyd in Safety Last, one of Welles’ inspirations for the picture, look like an accountant at a desk job. This was done with a shoe-string budget. There were no stunts, no carefully arranged shots that made a guy dangling from a clock a few feet above a platform look like he was dangling from a clock many stories in the air. Cotten and the man he has cuckholded, played with moustache-twirling zest by Edgar Barrier, scramble up and down Battery tenements, scooch around ledges and plank over chimneys with the greatest of ease.

The stand-outs for me are Joseph Cotten, who legs it over the rooftops of New York City with impressive gameness, grace and skill, the cinematography and the angled shots, surprising quick-cuts and close-ups that would come to define the Welles of Citizen Kane and after. Cotten makes Harold Lloyd in Safety Last, one of Welles’ inspirations for the picture, look like an accountant at a desk job. This was done with a shoe-string budget. There were no stunts, no carefully arranged shots that made a guy dangling from a clock a few feet above a platform look like he was dangling from a clock many stories in the air. Cotten and the man he has cuckholded, played with moustache-twirling zest by Edgar Barrier, scramble up and down Battery tenements, scooch around ledges and plank over chimneys with the greatest of ease.

Cinematographer Paul Dunbar pulled a rabbit out of a hat, making this two-buck-chuck of a film look way more expensive than it had any right to look. There are great shots capturing the geometry of the city (diagonal criss-cross fire escapes, stacks and stacks of boxes, background skyscrapers, hats covering the ground like confetti). Scenes set in “Cuba” were shot in a quarry over the Hudson River planted with palm trees Welles picked up at a local plant nursery. It’s downright eerie how well it all works.

But you don’t have to take my word for it just because I neglected to alert you to the impending airing. Thankfully the National Film Preservation Foundation has come to the rescue. When I posted about the restoration two years ago, the NFPF was raising money to digitize the movie and make it available for free on its website. Well, they were successful! You can watch the whole restored 66-minute work print online here. Being a particularly awesome organization, they have also uploaded an edited version which is an “educated guess” of how Welles might have pared down the footage for use alongside the play.

But you don’t have to take my word for it just because I neglected to alert you to the impending airing. Thankfully the National Film Preservation Foundation has come to the rescue. When I posted about the restoration two years ago, the NFPF was raising money to digitize the movie and make it available for free on its website. Well, they were successful! You can watch the whole restored 66-minute work print online here. Being a particularly awesome organization, they have also uploaded an edited version which is an “educated guess” of how Welles might have pared down the footage for use alongside the play.

The NFPF version (I’ve only seen the work print all the way through) is actually better than the version TCM showed, in my opinion, because the score is so much better. They’ve added a proper silent movie score whereas the TCM version was a very repetitive, sloooooow, minimalist composition that doesn’t match the slapstick action at all. They’ve also provided phenomenal notes explaining the full context of the play, comparing the original to drafts of the Mercury version so it’s much easier to follow the story. So yeah. Two thumbs most enthusiastically up.