The magnificent Renaissance ward of the oldest hospital in Europe, the complex of Santo Spirito in Saxia on the Vatican banks of the Tiber in Rome, has been restored. Two years of work have repaired the carved wooden ceiling, the masonry and the interior and exterior plaster, reviving the huge expanse of frescoes and polychrome painted wood architectural elements.

The magnificent Renaissance ward of the oldest hospital in Europe, the complex of Santo Spirito in Saxia on the Vatican banks of the Tiber in Rome, has been restored. Two years of work have repaired the carved wooden ceiling, the masonry and the interior and exterior plaster, reviving the huge expanse of frescoes and polychrome painted wood architectural elements.

The hospital started out as more of a hostel. The Schola Saxonum was founded in 727 by King Ine of Wessex on the ancient site of the pleasure gardens of the villa of Agrippina the Elder, daughter of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia, daughter of Augustus. Located on the Tiber under the shadow of Constantine’s ancient basilica of St. Peter’s, the schola provided accomodation and assistance to English travelers on pilgrimage ad limina apostolorum (“to the threshold of the apostles”). No fewer than 10 English kings, Alfred the Great among them, are known to have lived there for extended stays when they made their pilgrimages to Rome. In 794, one of those kings, Offa of Mercia, funded the addition of a xenodochio, a small building where strangers could get a little food and sleep, to the schola’s church.

Damaged by repeated fires and Saracen raids in the 9th century, the Schola Saxonum was repaired around 850 and again in the 11th century, but its use as accommodations for the crowned heads of Northern Europe was over by then. There were no Anglo-Saxon crowned heads after the Norman Conquest of England, for one thing, and Rome was no longer the only game in town when it came to major relics and martyrdom sites. Santiago de Compostela drew in huge numbers of pilgrims to venerate the relics of Saint James the Apostle. By the end of the 12th century, Canturbury was the premier destination for English pilgrims, drawn by the martyrdom site and miraculous relics of Saint Thomas Becket, and the schola in Rome languished from neglect.

Then Innocent III had a dream. Several, actually. In 1198, the Pope was plagued by a series of recurring dreams in which fishermen on the Tiber drew up the bodies of infants in their nets, illegitimate babies thrown into the river by adulterous women seeking to eliminate the living evidence of their sin. The fishermen presented the corpses of these drowned babies to the horrified pope. An angel then commanded Innocent to build a hospice for exposed babies.

Then Innocent III had a dream. Several, actually. In 1198, the Pope was plagued by a series of recurring dreams in which fishermen on the Tiber drew up the bodies of infants in their nets, illegitimate babies thrown into the river by adulterous women seeking to eliminate the living evidence of their sin. The fishermen presented the corpses of these drowned babies to the horrified pope. An angel then commanded Innocent to build a hospice for exposed babies.

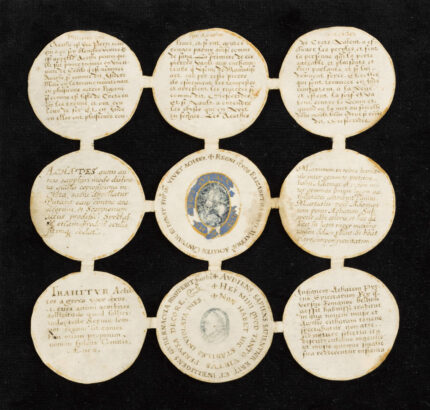

He rebuilt the schola and xenodochio into a hospital dedicated to the care of abandoned infants, the sick and indigent. Built into one of the exterior walls was a “wheel of the exposed,” a wooden lazy susan behind a little door on which infants could be placed anonymously.

In 1471, the hospital was ravaged by a fire that left it in shambles. The newly-elected Pope Sixtus IV visited the hospital and decried its dark, airless, crumbling environment. He ordered a full reconstruction of the facilities in anticipation of the upcoming 1475 jubilee year. The resulting structure, dubbed the Corsie Sistine (“Sistine Wards”), was the first example of Renaissance civic architecture built in Rome.

The hall is 120 meters (394 feet) long and 12 meters (39 feet) wide. It is divided into two spaces by an octagonal tiburio (a tower or lantern over the crossing of the galleries). Under the tiburio in the center of the Corsie is a ciborium (a canopy built four columns over an altar) that is the only known work in Rome of Renaissance master architect Andrea Palladio. The long walls facing each other are frescoed with more than 60 scenes depicting the founding of the hospital by Innocent III on one side and the life of Sixtus IV on the other. That’s 13,000 square feet of frescoes. You can see why it’s compared to the other Sistine Chapel, also built by Sixtus IV (although that one was famously frescoed under the papacy of his nephew, Julius II).

The hall is 120 meters (394 feet) long and 12 meters (39 feet) wide. It is divided into two spaces by an octagonal tiburio (a tower or lantern over the crossing of the galleries). Under the tiburio in the center of the Corsie is a ciborium (a canopy built four columns over an altar) that is the only known work in Rome of Renaissance master architect Andrea Palladio. The long walls facing each other are frescoed with more than 60 scenes depicting the founding of the hospital by Innocent III on one side and the life of Sixtus IV on the other. That’s 13,000 square feet of frescoes. You can see why it’s compared to the other Sistine Chapel, also built by Sixtus IV (although that one was famously frescoed under the papacy of his nephew, Julius II).

Soon hospitals built on the model of Santo Spirito in Saxia sprang up all over Europe. Before Innocent III’s dream, there were no hospitals dedicated to the care of the indigent and abandoned babies. By the end of the 15th century, there were 1,000 of them. Today the Renaissance ward is part of the modern Santo Spirito hospital complex and care and maintenance of the historic building played second fiddle to the hospital’s primary focus on patient care and medical research.

Financed by the Lazio Region for the ASL Roma 1, the restoration work has also focused on the ciborium which over the centuries, says the restorer Maria Rosaria Di Napoli, was “marked by dirt and [water] percolation from above. The greatest difficulty is balancing the different materials , because this is a jewel: we have polychrome and gilded wood, stucco, canvas, marbles. The colors were hardly seen anymore. Even the lantern, all made of wood, due to the water, had lost a lot of pictorial surface.

The Corsie Sistine is now open to visitors. In future, more historic hospitals in Italy are slated for restoration in a new initiative by the culture ministry to promote their extraordinarily deep bench of architecture and art off the beaten path of museums, churches and grand palazzi.

London’s National Gallery recently moved a monumental altarpiece by Renaissance master Filippino Lippi. It is 6’8″ high, 6’1″ wide and weighs 526 pounds, so this was no easy feat. The team captured it on video to give people a glimpse of the complex systems and technologies requires to handle fragile works of this scale.

London’s National Gallery recently moved a monumental altarpiece by Renaissance master Filippino Lippi. It is 6’8″ high, 6’1″ wide and weighs 526 pounds, so this was no easy feat. The team captured it on video to give people a glimpse of the complex systems and technologies requires to handle fragile works of this scale.