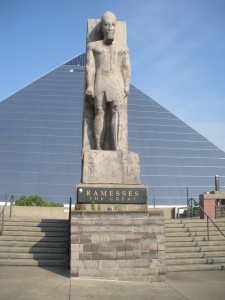

Memphis — the one in Tennessee — has a 50-ton, 25-foot-tall homeless pharaoh on its hands. It’s a fiberglass replica of a colossal statue of Ramesses the Great found in pieces in Memphis — the one in Egypt — and is the only officially permitted replica of the original Colossus of Ramesses in the world. It stands outside the Pyramid Arena, a sports arena in downtown Memphis on the banks of the Mississippi which is no longer in use as a sports venue and will instead be the locus of a new Bass Pro Shops megastore (plus other retail outlets, office space, even a river museum). Neither Bass Pro Shops nor the Memphis City Council think Ramesses the Great should have a second career as a mall cop, so the city is looking for a new home for their giant.

Memphis — the one in Tennessee — has a 50-ton, 25-foot-tall homeless pharaoh on its hands. It’s a fiberglass replica of a colossal statue of Ramesses the Great found in pieces in Memphis — the one in Egypt — and is the only officially permitted replica of the original Colossus of Ramesses in the world. It stands outside the Pyramid Arena, a sports arena in downtown Memphis on the banks of the Mississippi which is no longer in use as a sports venue and will instead be the locus of a new Bass Pro Shops megastore (plus other retail outlets, office space, even a river museum). Neither Bass Pro Shops nor the Memphis City Council think Ramesses the Great should have a second career as a mall cop, so the city is looking for a new home for their giant.

The City Council ran multiple advertisements in local press outlets looking for any takers who would keep Ramesses on display for the benefit of the people of Memphis. Only the University of Memphis, whose men’s basketball team once played in the Pyramid Arena, responded. The university offered to pay a token dollar and move the statue to its campus. Some people on the City Council are not thrilled with the idea, though, because the university is state-owned rather than city-owned. Also, the campus is in East Memphis; the ideal location would be more centrally located.

There’s also the small matter of the original agreement with Egypt. The Memphis City Council brought in Glen Campbell, the former curator of the Wonders series that brought the ancient limestone Ramesses colossus to Tennessee, and former Memphis mayor Dick Hackett to testify to the stipulations of the deal.

Campbell said that he, Hackett and the rest of Memphis delegation first saw the original statue in the Egyptian city called Memphis in 1986. It was lying in a ditch in about three big pieces and about a thousand smaller pieces.

When Hackett proposed moving it to the Bluff City for what would become the first Wonders exhibit, he suggested that it be displayed in pieces, just as it was in Egypt. Campbell recalled the response from an Egyptian antiquities official: “Pharaohs do not recline outside of the sands of Egypt.”

So the Memphis delegation agreed to restore the statue with funds from the Coca-Cola corporation, display it in Memphis and send it back to Egypt when they were done. They also won agreement to create a fiberglass replica to keep in the city. But there were conditions. The Americans had to agree to destroy the mold used to make the statue and send the Egyptians a videotape of the destruction, Campbell said.

And there were stipulations that are relevant to the current discussion: They also had to agree to keep the statue on public display somewhere in the city of Memphis, not to sell it and not to give it away, Campbell said.

Shall we bet on who that pithy Egyptian antiquities official was? I won’t name names, but I’m guessing his initials are Zahi and Hawass.

The agreement was signed by Hosni Mubarak, so an argument could be made that it’s invalid now and Memphis can do whatever it wants with the replica, but thankfully they’re not taking it that way. Keeping the statue on display for its educational and aesthetic value to the city of Memphis is their priority.

Bass Pro Shops is scheduled to begin renovations and construction of Pyramid Arena this month. The statue will remain in place until the matter is resolved.