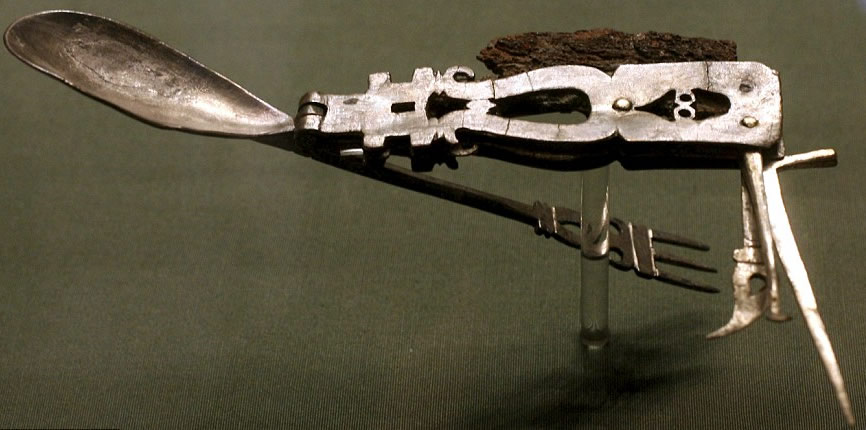

Yesterday Cambridge University’s Fitzwilliam Museum reopened its Greek and Roman gallery after a year and a half of renovations. One of its most prized items on display is an unspeakable cool folding multi-tool device that puts a Swiss Army knife to shame.

The tool features a knife, a spoon, a three-tined fork, a spike, a spatula, and a small pick. The spike may have been used as an escargot extraction device (snails were a very popular food in ancient Rome), and the pick may have been a toothpick. Archaeologists think the spatula may have helped pull sauce out of narrow-necked bottles.

It was made out of silver sometime between 200 A.D. and 300 A.D. Roman folding knives are not uncommon, but most of them are made out of bronze and have fewer parts. This is the ultra-deluxe version, and so probably belonged to a wealthy person who traveled a lot, like a merchant.

There are many other one of a kind items in the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Greek and Roman collection. It’s widely considered one of the best small museums in the country, and the building itself is a gem of elaborate Neo-Classical architecture. It has been fully restored preserving its historical features, but also adding extensive modernizations like a whole new lighting system that brings the many carvings and reliefs to new life.

Along with the gallery, the collection has been meticulously conserved, so there are pieces on display now that have never been seen before. For a fascinating glimpse into the renovation process, see this Project Progress blog written by the museum curators and staff. Sadly they seemed to have stopped making new entries in August of last year, but there are still some great pictures and descriptions of how it all went down.