Penitentials were handbooks listing many sins a confessor could be expected to encounter during private confession and the appropriate penances he should assign for each act (or the appropriate moneys the penitent should pay to commute a penance).

Penitentials were handbooks listing many sins a confessor could be expected to encounter during private confession and the appropriate penances he should assign for each act (or the appropriate moneys the penitent should pay to commute a penance).

They were first compiled by Irish monks in the 6th century when the practice of private confession began to supersede the public confessions of sins and imposition of penances of early Christianity and spread to the continent, continuing to be published through the 12th century even though they were officially condemned by the Catholic Church during the Council of Paris in 829.

The penances tended to be things like fasts, repetitions of psalms on your knees or standing, giving alms, and the sins were everything from fornication to murder. But it’s the fornication that took up the lion’s share of these handbooks, and every conceivable act was detailed along with the (heavy) price it exacted in penance.

Here’s an example from Corpus Christi College’s Corpus 190 of the Canons of Theodore:

Whoever fornicates with an effeminate male or with another man or with an animal must fast for 10 years.

Elsewhere it says that whoever fornicates with an animal must fast 15 years and sodomites must fast for 7 years.

If the effeminate male (bædling) fornicates with another effeminate male (bædling), (he is to) do penance for 10 years.

Whoever does this unintentionally (unwærlice) once must fast for 4 years; if it is habitual, as Basil says, for 15 years if he is not in orders and also one year (less?) so as a woman does. If it is a boy, for the first time, 2 years; if he does it again, 4 years.

If he is a boy, for the first time, 2 years; if he does it again, 4 years.

If he fornicates interfemorally (between the limbs), he must fast for 1 year or the 3 40-day periods.

If he defiles himself (masturbates), he is to abstain from meat for four days.

He who desires to fornicate (with) himself (i.e., to masturbate) and is not able to do so, he must fast for 40 days or 20 days.

If he is a boy and does it often, either he is to fast 20 days or one is to whip him.

If a woman fornicates [with another woman?] she must do penance for 3 years.

If she touches herself in the same way, i.e., in emulation of fornication, she must repent for 1 year.

One penance applies to a widow and a virgin; more (penance) is earned by her who has a husband if she fornicates.

Whoever ejaculates seed into the mouth, that is the worst evil. From someone it was judged that they repent this up to the end of their lives.

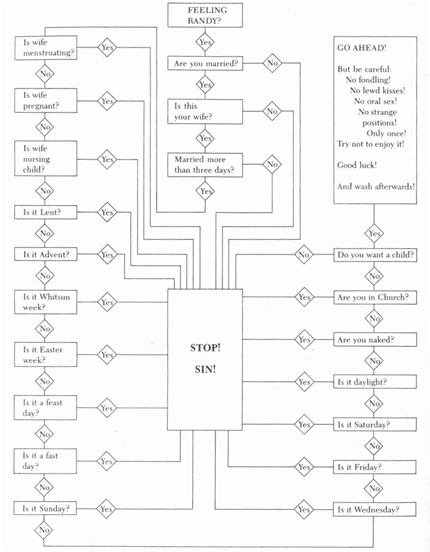

And it goes on and on like that. Marriage is no cure either, because there are endless strictures against marital sex as well. If it’s not procreative, it’s fornication. If it’s done on a holy day, it’s fornication. You see above what happens if it’s oral: you get a life sentence of penance.

The penitential writers saw marital sex as a concession, not as a right or even a gift from God. The pleasure it brought was inherently sinful, a gateway to lust, so sex within marriage should be carefully contained and scheduled to ensure the most possible procreation and the least possible pleasure. Married couples had to abstain regularly or the very state of their marriage would degenerate into an illegitimate and sinful union. Even the children born of sex during a period where the couple should have abstained — mainly based on the Church’s liturgical calendar and on the wife’s reproductive cycle — were to be considered bastards.

Which brings us to the inspiration of today’s little historical sermon. Many years ago in college I read a fascinating book called Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe by University of Kansas history professor emeritus James A. Brundage. It’s a remarkable analysis of Medieval authorities’ legal proscriptions about sex, starting with ancient Roman and Greek law codes, then moving on to Medieval strictures as seen in the penitentials, canon law, Germanic legal statutes, and ever so much more.

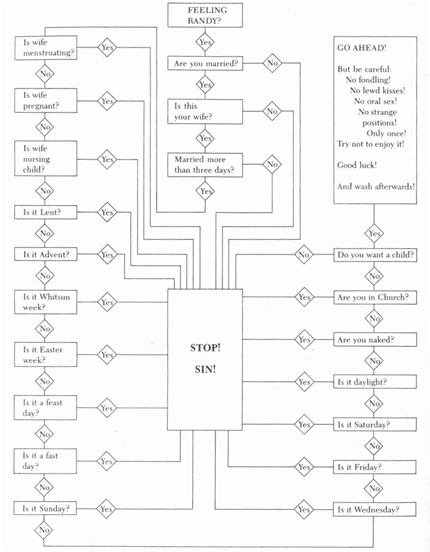

I regularly think of the chapter on the penitentials in particular, mainly because of one truly awesome flowchart. Unfortunately my copy of the book is squirreled away in my parents’ attic along with many of its college tome brethren, so yesterday when it popped into my head that I really need to blog about this greatest of historical graphs, I thought “Hey! There’s an interweb now! I bet I can find it online.” And so by Thor’s hammer I did.

It seems the chart has made a strong impression on many other people as well, and since Brundage’s book is standard in Medieval history and in history of sexuality studies, I am far from alone in wishing to pay it homage.

What it is is a flowchart Brundage compiled from many penitentials which helps the pious man figure out if he can have lawful intercourse. (Click for the large version.)

Genius, is it not? I bet you’ll find yourself thinking “STOP! SIN!” at random/randy times now too. :giggle:

That’s not to say that Medieval folks actually lived according to the flowchart rules, of course. There’s always a huge gap between proscription and reality. People did it then like we do it now: whenever they could. But it is a fascinating glimpse into the both prurient and ascetic world of Medieval confessor literature, and what kind of standards Medieval people might have measured themselves against.