Researchers published in the journal Science have dusted off fossils uncovered 40 years ago by the Marion Bonner family in western Kansas and found a new genus of giant plankton-eating bony fish among them.

Researchers published in the journal Science have dusted off fossils uncovered 40 years ago by the Marion Bonner family in western Kansas and found a new genus of giant plankton-eating bony fish among them.

Filter-feeding fish known as pachycormids were previously thought to have been a brief phase in evolutionary history, appearing 170 million years ago and then leaving the scene until whales, sharks and rays stepped into the niche 56 million years ago.

The new finds suggest that instead the pachycormids were a hugely successful species who set up shop in oceans all over the world from 170 million years ago until 65 million years ago, when the K-T extinction event that killed the dinosaurs killed them (and most everything else on earth) too.

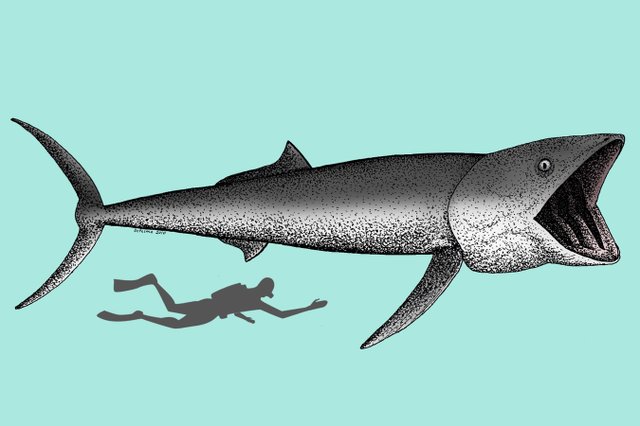

Co-author Kenshu Shimada, a research associate in paleontology at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History, told Discovery News that one of the fish he and his colleagues identified, Bonnerichthys, grew to around 20 feet in length and swam through a seaway covering what is today the state of Kansas. […]

For the study, led by University of Oxford scientist Matt Friedman, the researchers analyzed both old and new fish fossils found in England, the U.S. and Japan. The Kansas fish was previously thought to have been like a gigantic swordfish, bearing fang-like teeth on its jawbones.

“However, our close examination of the specimen showed that such a long snout and fang-like teeth were not present in the fish,” Shimada said. “Rather, with a blunt massive head, the fish had long toothless jawbones and long gill-supporting bones that are characteristic of plankton-feeding fishes.”

The European Jurassic species Leedsichthys was even larger at 30 feet. Their huge mouths were an asset in keeping their even huger bodies fed off tiny plankton. Like baleen whales today, pachycormids opened their mouths wide and gulped as much water as they could, filtering the plankton-packed water through its gills.

There’s some great background on the fossil-hunting Bonner family in this article.

Over the seven decades that Marion climbed and combed the chalk buttes; and over the four decades his children accompanied him, the Bonners helped science immeasurably. They were resourceful and careful; when they found unusual-looking bones, they gave them to scientists and let them take published credit for the scientifically described “discoveries.”

Their discoveries lay now in museums in Kansas, Chicago, Los Angeles and elsewhere. Grateful scientists named discoveries after the family: A few invertebrates. Pecten bonneri, a small-fin fish, pterandon bonneri, a flying reptile, niobrarateuthis bonneri, an ancient squid, found by Melanie.

This is their first genus, though.