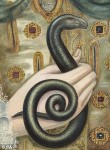

A late 16th century portrait of Queen Elizabeth I has reveled over time and degradation that she was originally depicted holding a coiled serpent in her hand instead of the innocuous nosegay she holds now. When an earlier image that has been painted over begins to show through, that is known as a pentimento, which means repentance in Italian.

A late 16th century portrait of Queen Elizabeth I has reveled over time and degradation that she was originally depicted holding a coiled serpent in her hand instead of the innocuous nosegay she holds now. When an earlier image that has been painted over begins to show through, that is known as a pentimento, which means repentance in Italian.

The portrait, painted by an unknown artist, some time in the 1580s or early 1590s, has not been on display at the National Portrait Gallery since 1921. You can clearly see the shadow of the serpent’s coming up from between her fingers and his tail coiling above her hand.

The serpent was a symbol of wisdom and reasoned judgment — as on the rod of Aesculapius, the physicians’ emblem — so that’s probably where our unknown artist was going with the imagery. He changed his mind, though (possibly in consideration of the common association of snakes with the devil and original sin), and quickly painted it over with a strangely-shaped but perfectly inoffensive little bouquet of roses.

Paint analysis shows that the snake was definitely made at the same time as the rest of the portrait. There is no varnish between the snake and flower layers, so we know it was painted right over.

The artist repented of his creation, if you will, and now the serpent is repenting him right back.

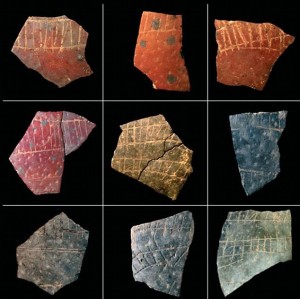

That’s not the only pentimento showing through, though. X-rays show that a portrait of an unknown woman lies underneath Elizabeth. Her head is higher and she’s facing the opposite way. If you click on the first picture at the top right of this entry, you can actually see her eye and nose in the left side of Elizabeth’s forehead and temple where the paint has chipped off. It looks like an absorbed twin.

Again the painter is unknown, but he’s definitely not the same person who would paint Elizabeth on the panel later. It’s very thoroughly painted but not quite complete. This lady is wearing a French hood, a garment fashionable from 1570 to 1580, so she might have been on the recycling heap for 10 to 20 years before getting royally repurposed.

The serpent portrait will go on display starting on March 13th along with 3 other interestingly altered paintings of Elizabeth I in an exhibit called Concealed and Revealed: The Changing Faces of Elizabeth I.

The four works range in date from the 1560s until just after her death in 1603. They were all modified in their time and have recently been re-examined using advanced scientific techniques of paint analysis, infrared and x-Ray photography so we can see more of what Elizabeth painters had hidden.

The four works range in date from the 1560s until just after her death in 1603. They were all modified in their time and have recently been re-examined using advanced scientific techniques of paint analysis, infrared and x-Ray photography so we can see more of what Elizabeth painters had hidden.

The most famous portrait of Elizabeth in the group, the Darnley portrait, originally showed the Queen with pink and rosy cheeks, so the image of the Virgin Queen always made up with white face and hands may turn out to be more of an artifact of faded paint than Elizabeth beauty standards.

In 2006, the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg found that 220 pieces worth up to $5 million from its enormous collection had been stolen and sold by a former curator. One of the lost items was a silver pendant of Peter the Great, part of a collection of 1,200 Peter the Great artifacts donated to the museum by the surviving family of Czar Nicholas II in 1947.

In 2006, the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg found that 220 pieces worth up to $5 million from its enormous collection had been stolen and sold by a former curator. One of the lost items was a silver pendant of Peter the Great, part of a collection of 1,200 Peter the Great artifacts donated to the museum by the surviving family of Czar Nicholas II in 1947.