Despite Japan’s alliance with Germany, Japanese officials collaborated to save thousands of Jews from Nazi-occupied Europe. The best known instance of a Japanese government employee defying Japanese immigration strictures to save Jews is Chiune Sugihara, an diplomat at the Japanese embassy in Lithuania who handed out travel visas to thousands of Jews in the early days of the war, even throwing blank visas out the window of his train as he left in August 1940 when the Russians annexed Lithuania.

Sugihara has been referred to as the “Japanese Schindler” because his transit visas allowed an estimated 6000 Jews to flee the country via the Trans-Siberian railway to Japanese-occupied Manchuria. He was honored in 1985 by Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial as one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

Once Jewish refugees got to Japanese territory, however, there was a whole other bureaucratic mountain to climb. They were stateless, often penniless and dumped in Manchuria. The Japan Tourist Bureau, apparently with the permission of Foreign Ministry, agreed to help distribute aid money sent by Jews in the US to Jewish refugees in Japan. This infusion of funds covered the immigration requirements that Sugihara had so consistently not given a crap about, and gave the refugees the means to get by and make plans.

Once Jewish refugees got to Japanese territory, however, there was a whole other bureaucratic mountain to climb. They were stateless, often penniless and dumped in Manchuria. The Japan Tourist Bureau, apparently with the permission of Foreign Ministry, agreed to help distribute aid money sent by Jews in the US to Jewish refugees in Japan. This infusion of funds covered the immigration requirements that Sugihara had so consistently not given a crap about, and gave the refugees the means to get by and make plans.

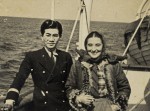

Tatsuo Osako was a Tourist Bureau employee assigned to act as an escort on ships carrying refugees across the Sea of Japan to port cities like Kobe and Yokohama where they could arrange for further transport. Osako kept pictures of some of the people he helped in a diary which was found in a drawer after his death in 2003. He didn’t write in the diary much, sadly, so all we know about who these people were is from their faces and the kind comments they wrote to Osako on the pictures.

“My best regards to my friend Tatsuo Osako,” is scrawled in French on the back of the picture, which is signed “I. Segaloff” and dated March 4, 1941. His fate is unknown.

An effort is under way to find the people in these portraits or their descendants, all of whom are assumed to be Jewish. Personal photos of such refugees, who often fled with few possessions, are rare. […]

Akira Kitade, who worked under Osako and is researching a book about him, has contacted Israeli officials for help and visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

The museum said he gave it about 30 photographs that he is trying to identify, and received a list of over 2,000 Jews who received travel papers that enabled them to reach Japan.

The Israeli ambassador to Japan, Nissim Ben Shitrit, is optimistic that they will be able to locate some of the people in the pictures and/or their descendants.

The comments on the pictures are written in languages (German, Polish, French) that mirror Germany’s conquest of Europe. Osako himself was so circumspect about his war experience that not even his daughters knew about the people he helped save. All we have in his words are a few lines he wrote in 1995 for a college alumni publication.

“The Jews that I saw at that time had no passports and were stateless, they were refugees that had fled Europe and were generally downcast, some with vacant eyes that projected the loneliness of people in exile,” Osako wrote.

But he also had time to make friends along the way — he notes that some were very helpful in his duties, and he recalls seeing Jewish women “of a rarely seen beauty.”