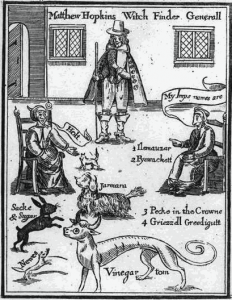

During the English Civil War, Matthew Hopkins and his colleague John Stearne traveled the Puritan counties of east England looking for witches. Hopkins styled himself the Witchfinder General and claimed to have been appointed by Parliament to root out witchcraft. Hopkins and Stearne cut a swathe through the women of Essex and surrounding counties between 1645 and 1647, inspecting them very carefully for moles and skin tags, aka devil’s marks from which familiars, imps and demons suckled witches’ blood like babies at the teat. They even had a staff of women “prickers” whose job was to stab, jab and probe suspected witches naked and shaved bodies for hidden marks.

During the English Civil War, Matthew Hopkins and his colleague John Stearne traveled the Puritan counties of east England looking for witches. Hopkins styled himself the Witchfinder General and claimed to have been appointed by Parliament to root out witchcraft. Hopkins and Stearne cut a swathe through the women of Essex and surrounding counties between 1645 and 1647, inspecting them very carefully for moles and skin tags, aka devil’s marks from which familiars, imps and demons suckled witches’ blood like babies at the teat. They even had a staff of women “prickers” whose job was to stab, jab and probe suspected witches naked and shaved bodies for hidden marks.

During those 2 years, Hopkins and Stearne were directly responsible for the hanging of 112 people for practicing witchcraft. That’s more than were killed in the previous century, and approximately 40% of the total number of witches killed during all persecutions in Britain between the early 15th and late 18th centuries. After their strenuous efforts, both Hopkins and Stearne retired in 1647 and wrote how-to books on finding witches and beating the Devil (for a modest fee, of course).

Hopkins’ The Discovery of Witches was highly influential in the New England colonies. Executions for witchcraft began in Massachusetts the year after the book was published and that first witch-hunt would last until 15 years until 1663. The Salem Witch Trials would pick Hopkins’ baton 30 years later between 1692 and 1693.

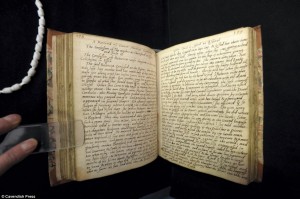

Puritan diarist and professional turner Nehemiah Wallington witnessed Hopkins’ trial of 33 young women in Chelmsford in July of 1645. He described what he saw and heard in great detail in his journals. So great a detail, in fact, that the story he told would become the 1968 Vincent Price cult classic The Witchfinder General.

Puritan diarist and professional turner Nehemiah Wallington witnessed Hopkins’ trial of 33 young women in Chelmsford in July of 1645. He described what he saw and heard in great detail in his journals. So great a detail, in fact, that the story he told would become the 1968 Vincent Price cult classic The Witchfinder General.

In the journal Hopkins – who died of tuberculosis in August 1647 – was referred to as the ”Gentle man” and Wallington wrote of how Rebecca confessed after seeing flames disappear when she became separated from her mother.

In the passage he wrote: ”Shortly after when she was going to bed the Devil appeared unto her again in the shape of a handsome young man, saying that he came to marry her.

”Asked by the Judge whether she ever had carnal copulation with the Devil she confessed she had. She was very desirous to confess all she knew, which accordingly she did where upon the rest were apprehended and sent unto the Geole [jail].

”She further affirmed that when she was going to the Grand Inquest she said she would confess nothing if they pulled her to pieces with pincers.

”Asked the reason by the Gentle man she said she found herself in such extremity of torture and amazement, that she would not endure it again for the world.

”When she looked upon the ground she saw herself encompassed in flames of fire and as soon as she was separated from her mother the tortures and the flames began to cease whereupon she then confessed all she knew.

”As soon as her confession was fully ended she found her contience so satisfied and disburdened of all tortures she thought herself the happiest creature in the world.”

The confession saved Rebecca’s life even as it doomed her mother and the other suspects. With no defense attorneys on their side and the whole trial generally being a chaotic sham, Rebecca was the only woman to be acquitted. The rest were all condemned, 19 of them hanged, 9 others reprieved.

The sole manuscript of Wallington’s account is kept at the historic estate of Tatton Park, but it’s in such delicate condition that it’s rarely seen in public. Thanks to the fancy imagine equipment and experts at the University of Manchester’s John Rylands Library, however, the journal is being digitized and will become part of an online exhibit.