A few weeks ago I blogged about a Rembrandt drawing that was stolen from an LA-area Ritz-Carlton hallway exhibit only to turn up two days later in the pastor’s office of an Encino church. Almost as soon as the story got traction in the press doubts cropped up as to whether the drawing was a Rembrandt at all (see Rowan’s comment on the original entry). No such drawing is listed in the accepted catalogs of Rembrandt’s work, and none of the experts contacted by reporters had ever heard of it. At least one expert thought the pen-and-ink drawing looked like it came from Rembrandt’s school instead of having been done by the master himself.

A few weeks ago I blogged about a Rembrandt drawing that was stolen from an LA-area Ritz-Carlton hallway exhibit only to turn up two days later in the pastor’s office of an Encino church. Almost as soon as the story got traction in the press doubts cropped up as to whether the drawing was a Rembrandt at all (see Rowan’s comment on the original entry). No such drawing is listed in the accepted catalogs of Rembrandt’s work, and none of the experts contacted by reporters had ever heard of it. At least one expert thought the pen-and-ink drawing looked like it came from Rembrandt’s school instead of having been done by the master himself.

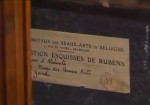

The Linearis Institute, owners of the drawing and sponsors of the Ritz-Carlton exhibit, made no rebuttal to these charges. Calls and emails from reporters asking for comment went answered, which is a little weird but not unheard of. Calls from police investigating the theft also went unanswered for a while, which is far weirder.

The weirdnesses continue to accumulate. The alleged Rembrandt is still in the possession of Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department because the Linearis Institute refuses to provide proof of ownership.

[T]he institute’s attorney, William Klein, said Linearis purchased “The Judgment,” from a legitimate seller. He said the institute’s officials just don’t want to say who that was.

“Things like that really are trade secrets,” Klein told The Associated Press. “We don’t believe we need to reveal trade secrets to get back what is ours.”

He acknowledged the institute has no trail of paperwork (called provenance in art-world speak) to prove “The Judgment” really is a Rembrandt. But he added that officials at Linearis believe it is and it shouldn’t matter what authorities think.

😮

Call me psychic, but something is rotten in Denmark. Best case scenario this so-called institute purchased a so-called Rembrandt from the back of a truck. Why else hide the seller from the police? If your sources of high-end art are “trade secrets” who sell Old Master drawings without ownership history then you’re buying on the black market, period. The difference is that a legitimate seller would trouble himself to counterfeit an ownership history replete with anonymous Swiss private collectors and girlfriends from Canada so that the new owners can have plausible deniability should the cops start sniffing around.

On top of that, it Linearis also isn’t interested in pressing charges against the thieves should they be found. Mr. Klein, Esq., says the institute is really only focused on finding a “compromise” that will allow them to get the drawing back. If the police arrest the thieves, the institute’s position is they can “do anything they need to do that’s in the interests of justice.” Sounds legit to me.