Folding stools built on a cross-frame are depicted on the walls of Egyptian tombs going back 4,000 years, and on Mesopotamian seals 500 years before that. By the time of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550-1070 B.C.), folding chairs were ubiquitous in the upper echelons of Egyptian society. Two were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, including one with an additional back piece so elaborately decorated and inlaid it is known as his throne, and many others have been discovered in the tombs of officials such as Kha, a foreman of works at Deir El-Medina under the reign of several pharaohs.

Folding stools built on a cross-frame are depicted on the walls of Egyptian tombs going back 4,000 years, and on Mesopotamian seals 500 years before that. By the time of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550-1070 B.C.), folding chairs were ubiquitous in the upper echelons of Egyptian society. Two were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, including one with an additional back piece so elaborately decorated and inlaid it is known as his throne, and many others have been discovered in the tombs of officials such as Kha, a foreman of works at Deir El-Medina under the reign of several pharaohs.

Although the x-frame design — a pin acting as a hinge between two crossed slats with animal skin or fabric stretched across the top for a seat — is among the simplest of furniture shapes, they were symbols of status and importance to the Egyptians. They ensured that even while on the move, the big shots got to sit up higher than everyone else who had to stand or sit on the ground. In Egypt women are never depicted sitting on a folding stool (rigid stools and chairs, yes, folding stools, no), although there are murals from around the same time (16th century B.C.) in the Palace of Knossos on Crete depicting aristocratic women sitting on x-frame chairs. Through the centuries, the form continued to be used by the likes of Augustus Caesar, medieval abbesses and Ming emperors.

It’s no surprise that the Egyptian cross-frame design spread far and wide over thousands of years, but what is surprising is that the Germanic and Nordic tribes of Bronze Age Europe were making x-frame folding stools as early as 1400 B.C., in parallel with New Kingdom Egyptians. The remains of at least 20 folding stools from the Bronze Age have been found north of the Elbe River in Germany and what is now Denmark. They are locally produced, so not imports from way down south.

Some historians think the tribal artisans came up with the folding stool form independently, but archaeologists Bettina Pfaff and Barbara Grodde have a different theory: Germanic furniture makers copied Egyptian ones. They posit that the chairs are so similar to each other in design, materials and dimension that the Nordic models must have been copies of Egyptian originals.

There were extensive trade networks supplying the elites with luxury goods from Northern Europe to Greece. Objects and raw materials were transferred from one area to the next by traders through a kind of relay system. The Bronze Age folding chairs, however, don’t follow the usual pattern. You find them in Egypt and you find them in northern Europe, but you don’t find them anywhere in between.

Is it possible, then, that a northern trader made the long journey from the Baltic Sea to Egypt, stole the design and brought it back home? As farfetched as the idea might seem, it is certainly plausible. Archaeologists have recently concluded that there were long-distance scouts more than 3,000 years ago who brought tin from Germany’s Erz Mountains all the way to Sweden. They probably traveled in oxcarts on dirt roads. Such ancient caravans probably also traveled along southern routes heading toward Africa.

Scholars are also determining the dates of such knowledge transfers. Egypt became a major power under Thutmose III (1479 to 1426 B.C.), whose armies reached the borders of modern-day Turkey. This changed the flows of goods. Even the Greek mainland fell under the spell of the pharaohs.

It was precisely at this time that a messenger from the North Sea coast could have been in Egypt and copied the chair’s design onto papyrus. Starting in 1400 B.C., the stools started being made in the far north and abruptly became fashionable. It appears that every prince of the moors was suddenly determined to have one of the new thrones from the south.

Craftsmen copied the exotic chairs down to the last detail. They often used oak or ash for the frame. A particularly fine piece discovered in Bechelsdorf, in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, has elaborate ornamentation, with decorative metal tassels that chime and a deerskin seat.

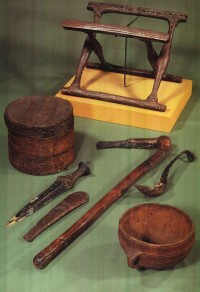

The only complete Nordic Bronze Age folding chair discovered thus far was discovered in 1891 from a barrow named Guldhøj (Gold Hill) near Vamdrup in Southern Jutland. Three oak coffins were found in the barrow, one looted in the Bronze Age, one belonging to a child, and the third holding a man wearing a woven jacket, leather shoes, a hat and the remnant of a mitten. Buried with him were a bronze weapon axe, a bronze dagger in a scabbard, a bronze pin, a turned wooden bowl decorated with hammered tin tacks, a box of bark, a horn spoon, and lying at his feet, a cross-frame folding stool.

The only complete Nordic Bronze Age folding chair discovered thus far was discovered in 1891 from a barrow named Guldhøj (Gold Hill) near Vamdrup in Southern Jutland. Three oak coffins were found in the barrow, one looted in the Bronze Age, one belonging to a child, and the third holding a man wearing a woven jacket, leather shoes, a hat and the remnant of a mitten. Buried with him were a bronze weapon axe, a bronze dagger in a scabbard, a bronze pin, a turned wooden bowl decorated with hammered tin tacks, a box of bark, a horn spoon, and lying at his feet, a cross-frame folding stool.

The chair is made of ash wood carved with patterns inlaid with black pitch. The seat is otter skin, although only a small part of it has survived. Dendrochronological analysis of the oak coffin dates the burial to 1389 B.C. The folding chair is a little older, from the second half of the 1400s B.C. The chair and the tin-decorated bowl indicate the deceased was a man of wealth and importance.

Pfaff believes that the Egyptian-style folding stools weren’t just for temporal leaders like chieftains and princes. Many of them were discovered in “poorly furnished graves” rather than in the burials of the wealthy political elite. She thinks these people may have been spiritual leaders or medicine men, so invested with social importance but not necessarily riches.