One of Benjamin Franklin’s many accomplishments was cofounding the first volunteer fire department of Philadelphia. It was December of 1736 and he was 30 years old.

Franklin was born in Boston but ran away when he was 17, even though he was a legally bound apprentice to his brother James, publisher of The New-England Courant. His brother had refused to publish his writing in the newspaper, so at just 16 years of age, Benjamin assumed the first of many personas, a middle-aged widow named Silence Dogood, and submitted 14 letters (click next to read them in order) all of which James unwittingly printed. Silence Dogood’s saucy humor quickly made her the talk of town and the subject of several marriage proposals. When James found out he had been duped, he was displeased, to say the least, and Benjamin decided it was best to get out of Dodge.

Fast-foward 13 years and Benjamin was a prominent Philadelphian and publisher of a newspaper of his own, the Philadelphia Gazette. He had already founded the first lending library in the country, and seeing the need for an organized response to fires, he advocated in the Gazette for the creation of a volunteer firefighting brigade. A fire in 1730 had started on a ship and spread to Fishbourn’s wharf on the Delaware River. All the warehouses on the wharf burned as did three homes across the street, causing thousands of pounds of damage (rumor has it Franklin had invested in some of that property), but calm winds had kept the fire from spreading all over town. Franklin noted that there had been no wind that night. If only the city had had some decent firefighting equipment and people who knew what they were doing, the fire could easily have been contained before it spread. He pointed out that it was only dumb luck that had kept Philadelphia from city-leveling fires.

Fast-foward 13 years and Benjamin was a prominent Philadelphian and publisher of a newspaper of his own, the Philadelphia Gazette. He had already founded the first lending library in the country, and seeing the need for an organized response to fires, he advocated in the Gazette for the creation of a volunteer firefighting brigade. A fire in 1730 had started on a ship and spread to Fishbourn’s wharf on the Delaware River. All the warehouses on the wharf burned as did three homes across the street, causing thousands of pounds of damage (rumor has it Franklin had invested in some of that property), but calm winds had kept the fire from spreading all over town. Franklin noted that there had been no wind that night. If only the city had had some decent firefighting equipment and people who knew what they were doing, the fire could easily have been contained before it spread. He pointed out that it was only dumb luck that had kept Philadelphia from city-leveling fires.

To further explore the argument, Benjamin Franklin whipped out yet another pseudonymous letter-writing persona. Quoting from Poor Richard’s Almanac (Benjamin was a pioneer of corporate synergy as well), “A.A.” wrote to the Gazette On Protection of Towns from Fire and was published in the February 4, 1735 issue.

Mr. Franklin, Being old and lame of my Hands, and thereby uncapable of assisting my Fellow Citizens, when their Houses are on Fire; I must beg them to take in good Part the following Hints on the Subject of Fires.

In the first Place, as an Ounce of Prevention is worth a Pound of Cure, I would advise ’em to take Care how they suffer living Brands-ends, or Coals in a full Shovel, to be carried out of one Room into another, or up or down Stairs, unless in a Warmingpan shut; for Scraps of Fire may fall into Chinks, and make no Appearance till Midnight; when your Stairs being in Flames, you may be forced, (as I once was) to leap out of your Windows, and hazard your Necks to avoid being over-roasted.

That’s good advice in any age, I’m sure we can agree.

After a few more articles along those lines, Franklin and four friends founded the Union Fire Company on December 7, 1736. There were 26 members of this first brigade. Each member agreed to bring six leather buckets — to carry water — and two stout linen bags — to rescue endangered property — to every fire upon first being alerted of the emergency. Members were appointed to different roles — water management, property protection, putting lights in neighboring windows — to ensure an organized and prompt reaction.

The Union Fire Company was immediately popular and they soon had more volunteers than they needed. When they reached 30 members, they refused new volunteers and instead told them to organize a new brigade. The more brigades, the more city could be covered. It worked, too. Philadelphia has never had one of those massively destructive fires like the Chicago Fire of 1871.

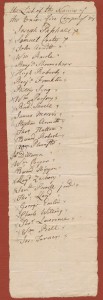

Tom Lingenfelter of Heritage Collectors Society, Inc. believes he has found a unique document from this watershed moment in firefighting history: a 1736 Union Fire Company member roster. It has yet to be authenticated so large grain of salt, but it appears to be a correct list of the 1736 membership written by Joseph Paschall, the company’s clerk and the first name on the list. Benjamin Franklin’s name is seventh. There are little x’s next to each name, possibly from taking attendance. If it does prove to be authentic, it will be the only known Union roster extant.

Tom Lingenfelter of Heritage Collectors Society, Inc. believes he has found a unique document from this watershed moment in firefighting history: a 1736 Union Fire Company member roster. It has yet to be authenticated so large grain of salt, but it appears to be a correct list of the 1736 membership written by Joseph Paschall, the company’s clerk and the first name on the list. Benjamin Franklin’s name is seventh. There are little x’s next to each name, possibly from taking attendance. If it does prove to be authentic, it will be the only known Union roster extant.

One of the names on the list is Philip Syng, the silversmith who would later make the inkstand used in the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Philip Syng was also intimately involved in another one of Benjamin’s pioneering efforts in the reduction of damage from fires: the country’s first property insurance company.

By 1752, there were eight volunteer fire companies in Philadelphia. Ever the innovator, Benjamin Franklin got together with his Union team and members of the other companies and founded The Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss of Fire, a mutual insurance company that offered seven year policies to cover the cost of fire damage to buildings only. (The company still exists today as The Philadelphia Contributionship.)

Again he enlisted the Gazette to promote the project and again it was an immediate success. They wrote 143 policies that first year, but it wasn’t until the next year that the first insured property, a house on Water Street, burned. Franklin assured Gazette readers that all damages would be repaired at no cost to the owner, and they were. It cost 154 pounds, almost a third of The Contributionship’s funds. Fortunately there weren’t another two fires on covered properties that year or the company would have gone under.

Philip Syng, along with Benjamin Franklin, was one of the first 12 directors of the company. He also designed The Contributionship’s logo: four hands clasping each other in support. The company made cast iron fire marks of that logo and required policy holders to affix them to the front of their houses, much like those home security companies do with decals today only far, far cooler.

Philip Syng, along with Benjamin Franklin, was one of the first 12 directors of the company. He also designed The Contributionship’s logo: four hands clasping each other in support. The company made cast iron fire marks of that logo and required policy holders to affix them to the front of their houses, much like those home security companies do with decals today only far, far cooler.

The fire marks probably got more attention from those same volunteer fire companies that the directors were all members of than houses not displaying the logo. The less fire damage, the less the payout, so it was in their self-interest to put out Contributionship-insured properties as quickly as possible. Despite that thumb on the scale, the volunteer firefighters still put out fires on all buildings, insured or not. They would simply present the property owner or another insurer with a bill for services rendered.