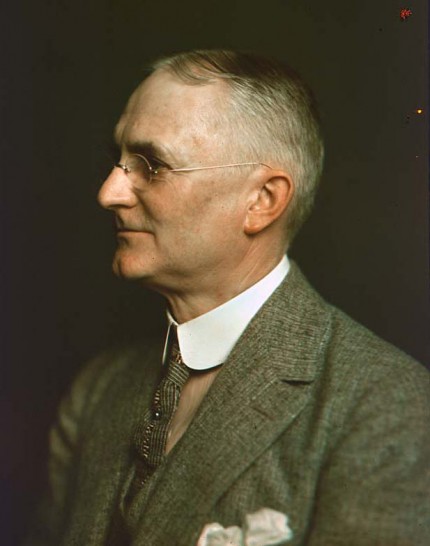

There is a beautiful set of early Kodachrome color pictures in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, including a portrait of George Eastman himself that was taken by photographer Joseph D’Anunzio in 1914 but looks like it could have been taken yesterday.

Impressive isn’t it? The flesh tones are particularly accurate. That was probably the strongest part of Kodak’s early experiments with the Kodachrome process, which entailed taking two glass plate photographs through green and orange-red filters, then dying the developed images and sandwiching them together with the emulsion sides in the middle. The process resulted in beautifully life-like skin and decent greens and reds, but could not produce a full spectrum of color.

The Eastman Kodak Company was trying with these Kodachrome experiments to create a color process that amateur photographers could master easily with limited equipment. The first attempts at color photography in the late 19th century required that three cameras with different color filters be used to record the identical subject. The three images would then be superimposed upon each other to produce a final picture.

In 1903, French inventors Auguste and Louis Lumière patented the Autochrome process which reduced the number of cameras to one, but it was far from amateur-friendly. Autochrome pictures were created using three batches of potato starch each dyed red-orange, violet or green. The starch was then applied to a newly varnished glass plate which was pressed through steel rollers to embed the colored starch particles into the surface. The gaps were filled with carbon black, the plate varnished again and brushed with a silver bromide emulsion. Once that was done, the photographer could put the plate in the camera and take a color picture. The subject had to sit completely still for 60 seconds, thus ensuring that the subjects were mainly landscapes, architecture and still lives.

Despite its complexity, Autochrome appealed to photographers for the beautiful color and painterly look of the finished product. There are some gorgeous examples in the Photographic History Collection at the National Museum of American History. See some otherworldly views of the 1915 San Francisco Panama Pacific International Exposition here. Some of the Kodachrome portraits were on display at that same exposition.

Despite its complexity, Autochrome appealed to photographers for the beautiful color and painterly look of the finished product. There are some gorgeous examples in the Photographic History Collection at the National Museum of American History. See some otherworldly views of the 1915 San Francisco Panama Pacific International Exposition here. Some of the Kodachrome portraits were on display at that same exposition.

Despite its facility with portraiture and the lack of dyed potato starch, the Kodachrome process with its limited color range couldn’t really compete with the full spectrum Autochrome. Eastman Kodak abandoned the process but kept working to find a new way to bring color to the photographic masses. In 1935 they succeeded, introducing the color Kodachrome film we analog old-timers remember well.

Speaking of groundbreaking old-timey photography, a Leica 0-Series camera, one of only 12 surviving 1923 prototypes of the Leica A, the first commercially successful camera to use 35mm film, sold at auction last Saturday at WestLicht Photographica in Vienna for a world record €2.16 million ($2.75 million).

Invented by optical engineer Oskar Barnack who worked in Leica’s microscope division, the Leica 0-series was the product of 15 years of trial and error. Barnack, an asthmatic and avid amateur photographer, wanted a lightweight camera with a collapsible lens that was easy to wield and could utilize 35mm film. Leica made 25 of them for testing and even though the feedback they got from photographers wasn’t entirely positive, in 1925 they took the plunge and built a first run of 1,000 Leica A cameras. By 1932, there were 90,000 of them sold.