It’s raining ancient blood, Hallelujah!  A research team from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) has found blood cells, muscle tissue, tendons, skin and hair on 31 2000-year-old obsidian knives from the ancient Cantona site in the central Mexico state of Puebla. This is the first definitive proof that human sacrifice was practiced in a Mesoamerican culture 1000 years before the Aztecs.

A research team from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) has found blood cells, muscle tissue, tendons, skin and hair on 31 2000-year-old obsidian knives from the ancient Cantona site in the central Mexico state of Puebla. This is the first definitive proof that human sacrifice was practiced in a Mesoamerican culture 1000 years before the Aztecs.

Ancient images showed priests using knives in blood-letting ceremonies and cuts found on bones suggested ritual dismemberment, but they couldn’t conclusively prove human sacrifice. Finding a large number of ancient knives with a variety of human tissues on them from the Cantona culture is strong evidence that there was a systematic ritualized practice of killing people.

INAH researcher Louisa Mainou first detected traces of human blood on a sacrificial knife from the site of Zethé in the state of Hidalgo, eastern Mexico, back in 1992. She continued to examine pieces archaeologists brought to the INAH lab and found more human remains, but they had to combine results from several different finds to get anything more than tiny trace material.

The set of 31 obsidian knives were found together at Cantona, an important religious center for the local pre-Hispanic culture. Mainou’s team received them from the archaeologists who excavated them two years ago. An initial examination found tiny spots on the obsidian. The knives were scanned inch by inch with a stereo microscope. They found that the spots were composed of what appeared to be blood cells, but they needed stronger technology to be sure.

The set of 31 obsidian knives were found together at Cantona, an important religious center for the local pre-Hispanic culture. Mainou’s team received them from the archaeologists who excavated them two years ago. An initial examination found tiny spots on the obsidian. The knives were scanned inch by inch with a stereo microscope. They found that the spots were composed of what appeared to be blood cells, but they needed stronger technology to be sure.

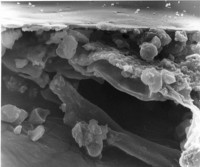

They removed some test spots with different scalpels for each obsidian knife and made samples for a scanning electron microscope which could see the substances in higher magnification and analyze their chemical makeup.

With help from specialists at Mexico’s National Autonomous University, they were studied under the scanning electronic microscope and found to contain red blood cells, collagen, tendon and muscle fiber fragments.

While historical accounts from Aztec times, as well as drawings and paintings from earlier cultures, had long suggested that priests used knives and other instruments for non-life-threatening bloodletting rituals, the presence of the muscle and tendon traces indicates the cuts were deep and intended to sever portions of the victim’s body.

“These finds confirm that the knives were used for sacrifices,” Mainou said. […]

Some knives in the test had more traces of red blood cells, while others had more skin, and others more muscle or collagen, “which suggest that each cutting tool was used for a different purpose, according to its form,” Mainou said

Like the Bolzano researchers did with the Iceman, this research team also found fibrin, a blood protein involved in the coagulation process indicating that the cutting was done on either living people or very recently deceased ones. The study also found silica, aluminum, calcium and potassium from the mineralization of the organic matter.