On July 3rd, 2012, 75 years after the news broke worldwide that Amelia Earhart, her navigator Fred Noonan and her Lockheed Model 10E Electra had disappeared over the Pacific the day before, a team from The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) departed Honolulu on the University of Hawaii oceanographic research ship R/V Ka Imikai-O-Kanaloa destined for the island of Nikumaroro in the southwestern Pacific Republic of Kiribati. Their goal was to search the deep waters around the uninhabited island for fragments of Earhart’s plane.

On July 3rd, 2012, 75 years after the news broke worldwide that Amelia Earhart, her navigator Fred Noonan and her Lockheed Model 10E Electra had disappeared over the Pacific the day before, a team from The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) departed Honolulu on the University of Hawaii oceanographic research ship R/V Ka Imikai-O-Kanaloa destined for the island of Nikumaroro in the southwestern Pacific Republic of Kiribati. Their goal was to search the deep waters around the uninhabited island for fragments of Earhart’s plane.

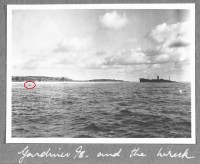

Artifacts, like a jar that may have once contained a popular 1930s anti-freckle cream, have been discovered on Nikumaroro before that could suggest the presence of a woman on the island before it was settled for a brief period starting in World War II. Also, a recent examination of a grainy picture of the western end of Nikumaroro taken by British Colonial Service officer Eric Bevington in October of 1937 noted a speck that could be nothing at all or it could be a chunk of Lockheed Installation 40650, a landing gear assembly used on the Lockheed Electra Model 10E.

TIGHAR raised $2.2 million from big ticket sponsors like Lockheed Martin, FedEx and the Discovery Channel (who sent a film crew to document the search for a special that will air on the Discovery Channel August 19th) and from many small donors to fund a deep sea search of the reef slopes of west Nikumaroro. They contracted deep ocean search and recovery specialists Phoenix International to conduct the difficult underwater searches, and the State Department helped facilitate an Antiquities Management Agreement granting TIGHAR an exclusive license to search and recover anything pertaining to the Earhart disappearance within the boundaries of the Republic of Kiribati.

TIGHAR raised $2.2 million from big ticket sponsors like Lockheed Martin, FedEx and the Discovery Channel (who sent a film crew to document the search for a special that will air on the Discovery Channel August 19th) and from many small donors to fund a deep sea search of the reef slopes of west Nikumaroro. They contracted deep ocean search and recovery specialists Phoenix International to conduct the difficult underwater searches, and the State Department helped facilitate an Antiquities Management Agreement granting TIGHAR an exclusive license to search and recover anything pertaining to the Earhart disappearance within the boundaries of the Republic of Kiribati.

The expedition was supposed to spend 10 days searching the mile-deep waters around Nikumaroro, but the technology they brought to accomplish the feat — including remote operated vehicles, autonomous underwater vehicles and multi-beam sonar — malfunctioned, and the precipitous vertical cliffs full of nooks and crannies that characterize the underwater environment to be explored proved even more of a challenge than expected. After five days, they decided to cut their losses and head back to Hawaii carrying a boat full of sonar data and high definition video but nary a single fragment of a Lockheed Electra Model 10E. The daily report from July 19th describes the team’s plight:

After discussion and analysis of the results so far, they have decided that there is very little point in extending the trip. The problem is the nature of the reef slope: a vertical cliff from 110 feet down to 250 feet, with a shelf that runs along that contour from Nessie to Norwich City. [Nessie is the name they gave to a certain location on Nikumaroro’s reef. The SS Norwich City is a British steamer which ran aground on the reef in 1929.] The airplane could have come to rest there briefly and lost pieces, but they have not found anything at all on that ledge.

From there the cliff goes almost vertically down to 1,000 – 1,200 feet, with another ledge. They will spend the rest of today searching that area. That is where the Norwich City wreckage came to rest, so maybe that’s where the airplane stopped.

But the question of searching for an airplane in this environment is even more basic than “what ledge” or “how far down.” Given what we now know about this place, is it reasonable to think that an airplane which sank here 75 years ago is findable? The environment is incredibly difficult, with nooks and crannies and caves and projections; it would be easy to go over and over and over the same territory for weeks and still not really cover it all. The aircraft could have floated away, as well.

So for the time they have left, they will focus on the ledges. Nothing could stick to the cliff walls, they are far too steep for anything to stick; and besides, if you get something (like a tether) caught, you can cause an avalanche (they did) and lose your ROV (they almost did).

Once the research vessel gets back to Hawaii, TIGHAR will go through the masses of data they’ve assembled. There’s still a chance they might find something pertinent somewhere in the sonar and video information even if they haven’t found the smoking Lockheed gun they were hoping to find. Keep your eye on the TIGHAR website for future announcements about the collected data, and tune to the Discovery Channel August 19th for the documentary.

To close on less of a bummer note, Google celebrated Amelia’s 115th birthday Tuesday with a neat Doodle and a lovely tribute written by Mark Roesler, the attorney for the Earhart estate.

To close on less of a bummer note, Google celebrated Amelia’s 115th birthday Tuesday with a neat Doodle and a lovely tribute written by Mark Roesler, the attorney for the Earhart estate.

Even as an adventurous dreamer, Amelia still knew that making a lasting legacy involved an element of risk. In a letter to her husband, George Putnam, she wrote, “Please know I am quite aware of the hazards. I want to do it because I want to do it. Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be but a challenge to others.” The message she leaves behind is especially evident to me: start living your life. Start setting aside your fears. Start believing it is acceptable to fail, knowing if you did not fail, you did not try. Without a doubt, her philosophy and lifetime accomplishments transcend time.