The Museum of Modern Art in New York City has a new exhibit opening Sunday dedicated to the development of design for children in the 20th century. Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900–2000 covers everything from furniture to clothes to toys to the suburban Chicago playhouse Frank Lloyd Wright designed as a kindergarten for the daughter of Avery and Queene Ferry Coonley in 1912.

The first chapter of the exhibit catalogue is available for free download (pdf) and it makes for fascinating reading. I didn’t realize how much of modernist design was inspired by progressive thought about childhood and children’s education. For instance, that playhouse Wright built for the Coonleys is packed with references to the ideas of Friedrich Froebel, who invented the whole concept of kindergarten in 1837. Froebel believed that play was how children learned about their environment and how things relate to each other. Toys, therefore, weren’t just something to bust out at recess but were integral to childhood development, hence his “gifts,” toys given to children at various stages starting with colored balls on strings, through to shapes, cubes, building blocks and beauty forms, blocks arranged to form increasingly complex geometric patterns.

The first chapter of the exhibit catalogue is available for free download (pdf) and it makes for fascinating reading. I didn’t realize how much of modernist design was inspired by progressive thought about childhood and children’s education. For instance, that playhouse Wright built for the Coonleys is packed with references to the ideas of Friedrich Froebel, who invented the whole concept of kindergarten in 1837. Froebel believed that play was how children learned about their environment and how things relate to each other. Toys, therefore, weren’t just something to bust out at recess but were integral to childhood development, hence his “gifts,” toys given to children at various stages starting with colored balls on strings, through to shapes, cubes, building blocks and beauty forms, blocks arranged to form increasingly complex geometric patterns.

The avant-garde art movements of the 1920s and 30s also took inspiration from and contributed new visions of childhood. Alma Buscher of the Bauhaus school designed colorful geometric toys and furniture that were entirely different in concept and execution from the miniature adult chairs and tables that characterized earlier childhood environments. The furniture she made for the nursery at the Haus am Horn, a house designed and decorated for the Weimar Bauhaus exhibition in 1923, is something you’ll still find in children’s rooms and classrooms. Her large and colorful building blocks were instant Bauhaus top sellers and remain so to this day.

The avant-garde art movements of the 1920s and 30s also took inspiration from and contributed new visions of childhood. Alma Buscher of the Bauhaus school designed colorful geometric toys and furniture that were entirely different in concept and execution from the miniature adult chairs and tables that characterized earlier childhood environments. The furniture she made for the nursery at the Haus am Horn, a house designed and decorated for the Weimar Bauhaus exhibition in 1923, is something you’ll still find in children’s rooms and classrooms. Her large and colorful building blocks were instant Bauhaus top sellers and remain so to this day.

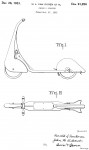

But it’s one particular item designed in 1933 that caught my eye and captured my heart. It’s the Skippy-Racer scooter, designed by John Rideout and Harold Van Doren for the American National Company in Toledo, Ohio. Behold its glory:

It’s on loan to MoMA from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts which bought it for an undisclosed sum after it was abandoned on the side of the street by some crazy person. That streamlined look made it a stand-out among the standard scooters sold at the time (or now, for that matter), and it was the primary selling point in catalogues and advertisements. The “new, original and ornamental design for a child’s scooter” was the justification for the patent as well.

Sleek scooter design wasn’t just for boosting sales, however.

Medical, educational, and design reformers believed that light, air, and hygiene should permeate all aspects of a child’s early environments. Designers developed new modern schools, nurseries, clothing, and furniture that were simple, light, and flexible. Physical education, delivered through schools and clubs, encouraged children to participate in modern forms of dance, gymnastics, and sport, whether as a means of inculcating collective values or of promoting health and self-expression.

It works on adults too. You couldn’t pry me off my Skippy-Racer with a crowbar and a gallon of axle grease.

The Century of the Child exhibit runs until November 5th, 2012. Sadly, Skippy-Racer rides are not included in the price of admission.