Surrealist master Salvador Dalí was a jack of many trades. He produced prodigious numbers of paintings, prints, and sculptures and collaborated with artists as diverse as fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli (go lobster dress!) and film director Alfred Hitchcock (Dalí designed the dream sequence in Spellbound). In 1927 he designed the sets for Spanish poet Federico García Lorca’s play Mariana Pineda. It would be 12 years before he followed up on his foray into theatrical design, and this time it would be a ballet of his own conception.

Léonide Massine was the principal choreographer of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and its principal male dancer after Nijinsky left in 1919. In the wake of Diaghilev’s death in 1929, the Ballets Russes disbanded. Impresarios, dancers and choreographers formed a number of spin-off companies in the ensuing years. Massine danced and choreographed for one of them (the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, later renamed the Original Ballet Russe), then co-founded a spin-off of the spin-off (also named the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, hence the former company’s name change).

Léonide Massine was the principal choreographer of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and its principal male dancer after Nijinsky left in 1919. In the wake of Diaghilev’s death in 1929, the Ballets Russes disbanded. Impresarios, dancers and choreographers formed a number of spin-off companies in the ensuing years. Massine danced and choreographed for one of them (the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, later renamed the Original Ballet Russe), then co-founded a spin-off of the spin-off (also named the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, hence the former company’s name change).

When Europe and most of the rest of the world plunged into war, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo toured the US and continued to do so throughout World War II. The company brought the rigor and beauty of Russian ballet to small towns all over the country that had never seen it before, leaving an indelible mark in the cultural landscape. You might recognize Léonide Massine as the choreographer and dance teacher Grischa Ljubov who plays the Shoemaker in the ballet-within-a-ballet-movie of the 1948 classic The Red Shoes.

When Europe and most of the rest of the world plunged into war, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo toured the US and continued to do so throughout World War II. The company brought the rigor and beauty of Russian ballet to small towns all over the country that had never seen it before, leaving an indelible mark in the cultural landscape. You might recognize Léonide Massine as the choreographer and dance teacher Grischa Ljubov who plays the Shoemaker in the ballet-within-a-ballet-movie of the 1948 classic The Red Shoes.

Salvador Dalí and his wife Gala fled France and settled in New York City in the summer of 1940, but he had already spent much of the year before there. His Dream of Venus exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows had caused something of a sensation with its sleeping nude Venus in a grotto and models swimming topless in an aquarium wearing long-sleeved bathing suits with the chest cut out, lobster girdles and rubber fish tails. The Internet Archive has an awesome video of the exhibit in full color (the Dalí portion starts 51 seconds in).

That year, 1939, is also when Dalí and Massine first came together to work on a ballet written and designed by the Surrealist. Bacchanale was a ballet in one act using the Venusberg Bacchanale from the first act of Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser as the score. Choreographed by Léonide Massine and danced by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Bacchanale was a spectacle depicting the dreams of mad King Ludwig II of Bavaria in which stories from Greek mythology, most prominently Leda and the Swan, mingled with historical figures like famed courtesan Lola Montez. Dalí wrote the libretto and designed the sets and costumes. It premiered on November 9, 1939 at the Metropolitan Opera House.

That year, 1939, is also when Dalí and Massine first came together to work on a ballet written and designed by the Surrealist. Bacchanale was a ballet in one act using the Venusberg Bacchanale from the first act of Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser as the score. Choreographed by Léonide Massine and danced by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Bacchanale was a spectacle depicting the dreams of mad King Ludwig II of Bavaria in which stories from Greek mythology, most prominently Leda and the Swan, mingled with historical figures like famed courtesan Lola Montez. Dalí wrote the libretto and designed the sets and costumes. It premiered on November 9, 1939 at the Metropolitan Opera House.

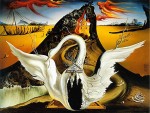

Of course it was scandalous. The sight of dancer Nini Theilade dressed neck to toe in a nude bodysuit emerging onto the stage from the gaping hole in the chest of a gigantic bleeding swan was a particularly memorable scene. The swan was painted on a theatrical backdrop in oils, and it still survives today. I can’t find a single good picture of it which doesn’t crop out its charming perimeter of cubbyholes with skeletons and bones stuffed in them, but there are two great angled shots here and here from when it was on display in Germany a couple of years ago as part of the Against All Reason, Surrealism Paris – Prague exhibit.

Of course it was scandalous. The sight of dancer Nini Theilade dressed neck to toe in a nude bodysuit emerging onto the stage from the gaping hole in the chest of a gigantic bleeding swan was a particularly memorable scene. The swan was painted on a theatrical backdrop in oils, and it still survives today. I can’t find a single good picture of it which doesn’t crop out its charming perimeter of cubbyholes with skeletons and bones stuffed in them, but there are two great angled shots here and here from when it was on display in Germany a couple of years ago as part of the Against All Reason, Surrealism Paris – Prague exhibit.

Dalí’s next collaboration with Massine was a high-minded conceptual piece under the guise of a mythological theme. Set to Franz Schubert’s Great C Major Symphony, Labyrinth told the story of Theseus’ battle with the Minotaur in the labyrinth and his escape by following the ball of yarn given to him by his lover Ariadne. According to the program notes, the thread symbolizes the tradition of classicism which all romanticism seeks to find. To explore this theme properly, Dalí wanted to use a real cow’s head in the scene where Theseus defeats the Minotaur, which the dancers would cut chunks off of and eat raw on stage. It didn’t happen, much to everyone but Dalí’s relief, I’m sure.

Dalí’s next collaboration with Massine was a high-minded conceptual piece under the guise of a mythological theme. Set to Franz Schubert’s Great C Major Symphony, Labyrinth told the story of Theseus’ battle with the Minotaur in the labyrinth and his escape by following the ball of yarn given to him by his lover Ariadne. According to the program notes, the thread symbolizes the tradition of classicism which all romanticism seeks to find. To explore this theme properly, Dalí wanted to use a real cow’s head in the scene where Theseus defeats the Minotaur, which the dancers would cut chunks off of and eat raw on stage. It didn’t happen, much to everyone but Dalí’s relief, I’m sure.

Labyrinth debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House on October 8th, 1941 to lukewarm reviews. The general consensus was that the sets overwhelmed the dance instead of complementing it. Massine had found it difficult to choreograph the Schubert piece, and he was kind of over the dancing being just a pretext for Dalí’s latest artistic installation. The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo still included Labyrinth along with Bacchanale on their 1941-1942 tour, though.

Massine kept one of Dalí’s backdrops from that tour, the one where Theseus struggles mightily with the Minotaur. Years later in the mid-1970s, he found it while cleaning his house and offered it to Nicolas Petrov, a Yugoslavian choreographer and former protégé of Massine’s who had founded the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre. Petrov had PBT patron Leon Falk Jr. buy the curtain for the company. It was kept at the PBT for a while, then Falk gifted the backdrop to the Carnegie Museum of Art with the understanding that the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre could use it at will.

Massine kept one of Dalí’s backdrops from that tour, the one where Theseus struggles mightily with the Minotaur. Years later in the mid-1970s, he found it while cleaning his house and offered it to Nicolas Petrov, a Yugoslavian choreographer and former protégé of Massine’s who had founded the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre. Petrov had PBT patron Leon Falk Jr. buy the curtain for the company. It was kept at the PBT for a while, then Falk gifted the backdrop to the Carnegie Museum of Art with the understanding that the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre could use it at will.

The museum has kept it in storage since they got it in October of 1976, unfurling it once in 2009 to document its condition, but although there was discussion at the time about how to display it for the public to enjoy, nothing came of it, possibly because its massive dimensions (26 1/2 feet high by 49 1/2 feet wide) make it 10 feet higher than the museum’s tallest gallery.

Theseus and the Minotaur is not currently on view at the museum, nor does it seem likely that its immense dynamism and dramatic impact will ever be allowed to grace the stage again, which is why it’s particularly awesome that another huge and dramatic backdrop from the Dalí-Massine oeuvre will tread the boards once more.

This one is from their third and final collaboration, a 1944 ballet called Mad Tristan, inspired by Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and set to music from the opera. In Dalí’s vision of the chivalric tale, Tristan is so maddened by love for Isolde that he sees her as the praying mantis devouring her mate. This mantis theme is something he had fiddled with before as part of his obsession with a pastoral painting by Jean-François Millet called The Angelus which Dalí saw as a depiction of mourning (he was convinced the couple are praying over the coffin of their dead child rather than a basket of potatoes) and of voracious sexuality.

This one is from their third and final collaboration, a 1944 ballet called Mad Tristan, inspired by Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and set to music from the opera. In Dalí’s vision of the chivalric tale, Tristan is so maddened by love for Isolde that he sees her as the praying mantis devouring her mate. This mantis theme is something he had fiddled with before as part of his obsession with a pastoral painting by Jean-François Millet called The Angelus which Dalí saw as a depiction of mourning (he was convinced the couple are praying over the coffin of their dead child rather than a basket of potatoes) and of voracious sexuality.

In the Surrealist magazine Minotaure, Dalí had published an article entitled “Paranoiac-Critical Interpretation of the Obsessive Image of The Angelus by Millet” which he subtitled: “A Chance Encounter of an Umbrella and a Sewing Machine on a Dissecting Table.” From the 1933 article:

The umbrella… as a result of its flagrant and well-known phenomenon of erection, would be none other than the masculine figure in the Angelus which in the picture, as the reader will do me the favor of remembering, is trying to hide his state of erection — and thereby merely succeeding in drawing attention to it — by the shameful and compromising position of his own hat. Opposite him, the sewing machine … goes so far as to invoke the mortal and cannibal virtue of her sewing needle, the activity of which may be identified with that super fine perforation of the praying mantis “emptying” her male.

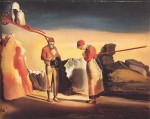

That same year he made Atavism at Twilight, now in the Kuntsmuseum in Bern, Switzerland, one of several paintings inspired by this view of Millet’s work. Notice the red wheelbarrow sticking out of the skull-headed man’s back and the red pitchfork sticking out of the praying mantis lady’s back. When designing the backdrop for the final climactic scene of Mad Tristan, Dalí employed that same imagery and then some, creating a large scale Surreal vision of the wounded and bleeding Tristan wearing a dandelion beret while ants walk all over a crack in his shoulder. Across from him is Isolde, reaching towards him with both hands. A wheelbarrow grows out of her back and two red crutches frame the scene on either side. The backdrop is 30 feet high and 50 feet wide.

That same year he made Atavism at Twilight, now in the Kuntsmuseum in Bern, Switzerland, one of several paintings inspired by this view of Millet’s work. Notice the red wheelbarrow sticking out of the skull-headed man’s back and the red pitchfork sticking out of the praying mantis lady’s back. When designing the backdrop for the final climactic scene of Mad Tristan, Dalí employed that same imagery and then some, creating a large scale Surreal vision of the wounded and bleeding Tristan wearing a dandelion beret while ants walk all over a crack in his shoulder. Across from him is Isolde, reaching towards him with both hands. A wheelbarrow grows out of her back and two red crutches frame the scene on either side. The backdrop is 30 feet high and 50 feet wide.

Massine had left the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo due to conflicts with its manager and was by then working with Ballet International, a company founded by Chilean impresario and great eccentric Marquis George de Cuevas. Mad Tristan premiered at the International Theatre in New York City on December 15th, 1944.

Somehow, the backdrop from the final scene made its way to the Metropolitan Opera where it was found in prop storage in 2009. It was sold to an anonymous art collection in Switzerland for an undisclosed sum. There it was restored and there it has remained until now, but instead of falling down the collection rabbit hole, this great piece which has not been seen in public since 1944 is going to get a whole new life in a context that Dalí would surely have appreciated. It’s going to be a backdrop again for an acrobatic circus troupe.

The collectors contacted Daniele Finzi Pasca of the Company Finzi Pasca, who has directed shows for Cirque du Soleil and the closing ceremonies of the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, asking him if he could think of a cool way to use the backdrop.

“The foundation decided not to put it in a museum,” Finzi Pasca said in an interview. “They preferred to come back with this backdrop to the theatre. We accepted the challenge and the invitation because it was exactly an element that can help us tell the story that we had in mind.”

The show, which had begun taking shape as an exploration of dreams and ideas, soon coalesced around the Dali.

“Working with the surrealism gives the opportunity to explore these ideas, to create strange images,” Finzi Pasca said of the show, which will include the company’s trademark acrobatics as well as theatre. “It’s a show that’s funny and also moving and touching.”

The new show, La Verita, will debut at Montreal’s Théâtre Maisonneuve on January 17th, 2013. After that, it will tour South America and Europe. There are no tour dates scheduled in the United States as of yet.