One of my favorite areas of study (on any day of the year, not just Halloween, although it certainly dovetails nicely with the grisly ghouls from every tomb closing in to seal your doom) is now the subject of a multi-disciplinary research program at the University of Leicester: the fate of executed criminals in Britain between the 17th and 19th centuries. Generously funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is also offering a critical workshop on how best to cope with a zombie outbreak, Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse brings together experts in archaeology, medical history, folklore, philosophy and literature from the University of Leicester, the University of Hertfordshire and the National University of Ireland to examine how the corpses of executed criminals were used as cautionary tales in the gibbet and as sources of scientific knowledge on the dissection table, the significance they were imbued with culturally and morally, and the lasting effect they had on the physical landscape and on our attitudes about the treatment of the dead body.

One of my favorite areas of study (on any day of the year, not just Halloween, although it certainly dovetails nicely with the grisly ghouls from every tomb closing in to seal your doom) is now the subject of a multi-disciplinary research program at the University of Leicester: the fate of executed criminals in Britain between the 17th and 19th centuries. Generously funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is also offering a critical workshop on how best to cope with a zombie outbreak, Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse brings together experts in archaeology, medical history, folklore, philosophy and literature from the University of Leicester, the University of Hertfordshire and the National University of Ireland to examine how the corpses of executed criminals were used as cautionary tales in the gibbet and as sources of scientific knowledge on the dissection table, the significance they were imbued with culturally and morally, and the lasting effect they had on the physical landscape and on our attitudes about the treatment of the dead body.

“This is a great opportunity to study the history of the body at a fascinating time,” said Professor Sarah Tarlow, an archaeologist at the University of Leicester and the leader of the team. “This is a key period in the development of modern medical knowledge, where the inside of the body was carefully explored and described by anatomists. At the same time it was generally believed that the touch of a hanged man’s hand could cure cancers of the neck, and that suicides should be buried with a stake through their bodies.

“The emotional power of the dead body of the criminal was exploited by the State to enforce conformity with the law, they were exploited as sources of scientific or medical knowledge; they gave meaning to places in the landscape, for example, ‘Gibbet Hills’ and so on. At a popular level, their ghosts were believed to stalk the living and their bodies to be places of lurking malevolence which might threaten our comfortable lives – as Frankenstein’s monster did.”

(I always feel compelled to defend the creature when he’s described as intrinsically evil. He was intrinsically repulsive with his papery skin and yellow eyes, but he was much more than the sum of his Abby Normal parts and had his creator/father not been so mean to him, he would never have killed children and best friends and nice ladies on their wedding night. It’s the hubristic scientist, the modern Prometheus, the grave-robbing narcissist who thinks he can do whatever he wants in the name of scientific advancement whose selfishness, cowardice and obstinacy destroy everyone he loves.)

The team will spend five years following the journey of the criminal body through six strands of study. The first is the criminal justice system, wherein will be examined the crime itself, the legal proceedings at trial, the sentences which were sometimes applied and sometimes commuted, with a subsequent focus on how the body of the executed criminal was used to support the judicial system that created it. Although there’s been plenty of study of the crime and punishment from trial to execution, this research will tread new ground in its study of the body after execution. The team will trace the physical movements of the bodies through the justice system and the people — sheriffs, judges, court officers, legal commentators — involved in the decision-making process.

The team will spend five years following the journey of the criminal body through six strands of study. The first is the criminal justice system, wherein will be examined the crime itself, the legal proceedings at trial, the sentences which were sometimes applied and sometimes commuted, with a subsequent focus on how the body of the executed criminal was used to support the judicial system that created it. Although there’s been plenty of study of the crime and punishment from trial to execution, this research will tread new ground in its study of the body after execution. The team will trace the physical movements of the bodies through the justice system and the people — sheriffs, judges, court officers, legal commentators — involved in the decision-making process.

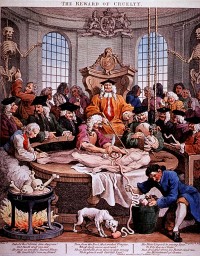

Strand two focuses on the voyage of the criminal corpse through the anatomical world, how executed bodies were used to sustain the explosion of private anatomy schools, all of which required copious numbers of cadavers for their students to get their money’s worth. The team will examine the condition of the corpses when they arrived and how they were dissected and put on display. The Wellcome Collection, the museum of medical history connected to the Trust funding this program, has a fair few human specimens which traveled this road.

The third strand, “Placing the Criminal Corpse,” pivots off the first two strands to focus on the corpse on display, whether in the gibbet or in the anatomy class or museum, through to its burial. Very few bodies of executed criminals can be firmly located today. They couldn’t be buried in consecrated ground, so where did these gibbeted, dissected, dismembered bodies wind up?

The third strand, “Placing the Criminal Corpse,” pivots off the first two strands to focus on the corpse on display, whether in the gibbet or in the anatomy class or museum, through to its burial. Very few bodies of executed criminals can be firmly located today. They couldn’t be buried in consecrated ground, so where did these gibbeted, dissected, dismembered bodies wind up?

Strand four looks at how the dead sustained life. By studying medical literature and contemporary sources, the team will examine how the dead, whether through anatomical study or through magical and healing cultural traditions, cured or prevented illness and kept people alive.

Next up is “The Criminal Corpse in Pieces,” a particularly Halloween-appropriate strand of research which looks at the part played by the criminal corpse in fiction. The bodies of executed criminals frequently starred in the literature of this period as vengeful ghosts, loci of punishment and relics of supernatural power (the Whitby Hand of Glory, for example, the hand of a hanged man which, when holding a candle made from the fat of the same executed criminal, was said to render motionless whomever it was given to, or to unlock all doors). This connects to strand four in its examination of folkloric traditions but will study the interplay between traditions and literary fiction.

Next up is “The Criminal Corpse in Pieces,” a particularly Halloween-appropriate strand of research which looks at the part played by the criminal corpse in fiction. The bodies of executed criminals frequently starred in the literature of this period as vengeful ghosts, loci of punishment and relics of supernatural power (the Whitby Hand of Glory, for example, the hand of a hanged man which, when holding a candle made from the fat of the same executed criminal, was said to render motionless whomever it was given to, or to unlock all doors). This connects to strand four in its examination of folkloric traditions but will study the interplay between traditions and literary fiction.

The last strand, “The Criminal Corpse Remembered,” brings it all together through a comparative analysis of historical attitudes towards the criminal corpse and contemporary ones. It will look at how our own anxieties and ambivalence about how we treat the dead are informed by the symbolic and practical significance with which the criminal corpse was imbued from the late 17th century through the mid-19th.

The Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse project website is already great reading but will continue to expand as the program proceeds. Any published material that comes out of the project or that is relevant to it will be posted on the publications page. Any news stories and events connected to the project will be posted on the news page.

The Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse project website is already great reading but will continue to expand as the program proceeds. Any published material that comes out of the project or that is relevant to it will be posted on the publications page. Any news stories and events connected to the project will be posted on the news page.

There’s one particularly exciting event hosted by University of Hertfordshire Professor of Social History Owen Davis (one of the Strand Four researchers). It’s a reenactment of the inquest of the infamous “Elstree Murder” case of 1823, which will be held on November 13th at 8:00 PM in the Old Barge Pub in Hertford. It’s free of charge to all comers. Just show up and you’ll get to be a part of the inquest jury that decides whether John Thurtell, the wastrel son of the Mayor of Norwich, and his accomplices murdered the solicitor William Weare because he had cheated John out of £300 in a card game.

After you’re done presiding over this shocking case, you can head over to the Museum of London to see its Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men exhibit, which has been getting rave reviews.