The Elms, a Gilded Age mansion in Newport, Rhode Island designed by architect Horace Trumbauer for coal baron Edward Julius Berwind, opened its doors to the first of many lavish parties in 1901. In keeping with the exterior, copied almost exactly from the Château d’Asnières outside of Paris, the interior of the home was decorated in opulent 18th century French style by Jules Allard. The interior decorating firm of Allard and Sons was headquartered in Paris, but its New York branch was the pre-eminent decorator for the scions of New York high society and their Rhode Island summer homes.

The Elms, a Gilded Age mansion in Newport, Rhode Island designed by architect Horace Trumbauer for coal baron Edward Julius Berwind, opened its doors to the first of many lavish parties in 1901. In keeping with the exterior, copied almost exactly from the Château d’Asnières outside of Paris, the interior of the home was decorated in opulent 18th century French style by Jules Allard. The interior decorating firm of Allard and Sons was headquartered in Paris, but its New York branch was the pre-eminent decorator for the scions of New York high society and their Rhode Island summer homes.

The Berwinds were avid collectors of 18th century French and Venetian paintings (among other things) and had a number of important pieces by the likes of Francesco Guardi, Jean Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher that are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In keeping with the Berwinds’ pre-existing collection, Allard acquired ten major early 18th century works by six Venetian artists including Sebastiano Ricci and Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini. Two of the four largest paintings were hung in the entrance foyer, the other two in the dining room.

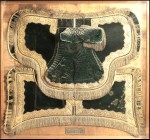

The six remaining canvases were all placed in the dining room. Allard designed the room around the paintings, creating a cast plaster ceiling decorated in gold St. Mark’s lions, elaborate marble-topped sideboards and six doors with geometric panels over which the artworks were placed much like they had been in the palace in Venice whence they came.

The paintings are a set originally commissioned by the influential, wealthy Corner family for Cà Corner, their sumptuous palace on Venice’s Grand Canal. The theme is the history of the Corners, which according to family lore stretched all the way back to the Roman patrician gens Cornelia. The four large paintings celebrate the life of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, the great Roman general who defeated Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 B.C., ending the Second Punic War and Carthage’s days as a major Mediterranean power. The six smaller paintings commemorate the feats of distinguished political and military leaders from the Corner family in the history of Venice.

The paintings are a set originally commissioned by the influential, wealthy Corner family for Cà Corner, their sumptuous palace on Venice’s Grand Canal. The theme is the history of the Corners, which according to family lore stretched all the way back to the Roman patrician gens Cornelia. The four large paintings celebrate the life of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, the great Roman general who defeated Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 B.C., ending the Second Punic War and Carthage’s days as a major Mediterranean power. The six smaller paintings commemorate the feats of distinguished political and military leaders from the Corner family in the history of Venice.

Allard bought them complete with their original gilded frames so they would hang in The Elms just as they had in Cà Corner. The Corner paintings would give The Elms the distinction of having the most complete series of paintings dedicated to Venetian history outside of Venice.

After Mrs. Berwind died in 1922, Edward asked his sister Julia to move in and act as official hostess at The Elms. She did so and continued to do so long after his death in 1936, living at The Elms in grand style until her own death in 1961 at the age of 96. She left The Elms to a nephew who wanted nothing to do with it. Neither did anyone else in the family. By then, the Gilded Age lifestyle of dozens of servants and endless maintenance headaches had lost its appeal even to the rich. The Berwinds decided to cut their losses and sell out. The family put the contents of the mansion up for auction in June of 1962, and then sold The Elms to a developer who planned to raze it and build something atrocious in its place.

The Preservation Society of Newport County stepped in to prevent this dire fate. In 1962, with just weeks to go before the mansion’s destruction, they raised $116,000 to purchase The Elms property and open it to the public as a museum. The auction of the contents was a done deal, however. The furniture and art work were scattered. The six smaller Venetian paintings were sold as a group for $14,000. The four large paintings from the Venetian set stayed in place simply because they could not be removed. They’re 12 feet by 12 feet and had been stuck to the walls with white lead to ensure they didn’t topple over from their own weight.

In the years since then, the Preservation Society has been able to track down and buy back some of the lost furnishings and art. The massive dining room table was being used in a conference room at Brown University. In 2004, they raised $250,000 to buy back four of the six Venetian paintings from New York art dealers Wildenstein & Company. The last two were with Wildenstein & Co. as well, but they were the most valuable and the Preservation Society simply could not raise that kind of money.

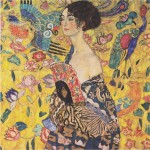

Both of the final two paintings are by Sebastiano Ricci. One of them, Anteros Pleads With Atropos, depicts winged Anteros, god of requited love, son of Aphrodite, brother of Eros, pleading with Atropos, one of the Fates, not to cut the threads of the life of the three wounded men in the painting. The three men are a Venetian man with his arm around a Slav, and another Venetian man seated in front of them. In the distance you can see a view of Venice. Art historians believe this is a reference to Alvise Corner who in 999 A.D. helped conquer Dalmatia for Venice. Anteros’ presence paints the conquest as a coming together of lovers in shared feeling, not the subjugation of Slavic peoples by Venetian force.

Both of the final two paintings are by Sebastiano Ricci. One of them, Anteros Pleads With Atropos, depicts winged Anteros, god of requited love, son of Aphrodite, brother of Eros, pleading with Atropos, one of the Fates, not to cut the threads of the life of the three wounded men in the painting. The three men are a Venetian man with his arm around a Slav, and another Venetian man seated in front of them. In the distance you can see a view of Venice. Art historians believe this is a reference to Alvise Corner who in 999 A.D. helped conquer Dalmatia for Venice. Anteros’ presence paints the conquest as a coming together of lovers in shared feeling, not the subjugation of Slavic peoples by Venetian force.

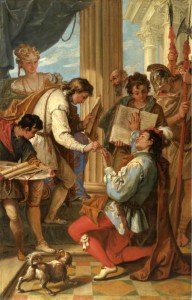

The second painting says it all in the title. It’s The Investiture of Marco Corner as Count of Zara in 1344 and depicts Marco Corner, who would become Doge of Venice in his 60s, as a young man. Zara (Zadar in Croatia today) was much fought over by Venice. Zara was one of the cities that appealed to Venice to quash the Neretvian pirates in 998, which was the pretext for the conquest of Dalmatia depicted in the Anteros painting. It bounced back and forth between Venetian authority, the Kingdom of Hungary-Croatia, and the Byzantine Empire for centuries. In 1344, Marco Corner was appointed its Count.

The second painting says it all in the title. It’s The Investiture of Marco Corner as Count of Zara in 1344 and depicts Marco Corner, who would become Doge of Venice in his 60s, as a young man. Zara (Zadar in Croatia today) was much fought over by Venice. Zara was one of the cities that appealed to Venice to quash the Neretvian pirates in 998, which was the pretext for the conquest of Dalmatia depicted in the Anteros painting. It bounced back and forth between Venetian authority, the Kingdom of Hungary-Croatia, and the Byzantine Empire for centuries. In 1344, Marco Corner was appointed its Count.

It’s the Investiture in particular which broke the Preservation Society of Newport County’s bank for so long. It was put up for auction at Sotheby’s in London in 2009. The pre-sale estimate was $643,000-$964,000. Anteros was also for sale in that same auction with a more modest but still exorbitant estimate of $241,000-$320,000. Fortunately for The Elms, neither of them sold, nor have they sold since then.

Finally this year the Society was able to strike a bargain with the owners: $650,000 for both paintings. Since the price was never going to get any better than that, a vigorous fundraising appeal was successful thanks to a generous small group of donors. It’s the largest purchase the Preservation Society has ever made.

Now the entire dining room is back to its 1901 splendor, and the entire Corner collection is back in one place again. You can see what the room used to look like before the recovery of the table and the smaller paintings in this virtual tour. It really does look forlorn with the plain, thin table and the gaps above the doors where the paintings used to be, which is weird considering what an explosion of Rococo it is.