Two recently discovered marble reliefs from the appropriately named House of the Dionysiac Reliefs in Herculaneum will be on display again for the first time since the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. hid them under 100 feet of volcanic ash. The reliefs will be part of a new exhibition at the British Museum called Life and death in Pompeii and Herculaneum which will display more than 250 artifacts on loan from Archaeological Superintendency of Naples and Pompeii and objects in the British Museum collection. Many of the pieces on loan have never before traveled outside of Italy.

The focus of the exhibit isn’t just to show off the beauties preserved at Pompeii and Herculaneum but rather to give visitors a glimpse into the daily lives of the people who lived in those towns under the shadow of Vesuvius. Along with entire rooms of frescoed walls, statuary, expensive jewelry and mosaics there are quotidian objects like a loaf of bread and a wooden crib that looks like it could have been made yesterday. The idea is to show the day-in-the-life snapshot captured by the unique preserving force of the eruption. The room of frescoes, for instance, will be on display along with plaster casts of the family who lived there. The bodies of a man, woman and small children huddled together in terror under the stairs of their house left uncanny impressions in the volcanic ash from which plaster casts were made. A dog rolling in agony on his back, one of the most famous of the casts, will also be part of the exhibition.

The focus of the exhibit isn’t just to show off the beauties preserved at Pompeii and Herculaneum but rather to give visitors a glimpse into the daily lives of the people who lived in those towns under the shadow of Vesuvius. Along with entire rooms of frescoed walls, statuary, expensive jewelry and mosaics there are quotidian objects like a loaf of bread and a wooden crib that looks like it could have been made yesterday. The idea is to show the day-in-the-life snapshot captured by the unique preserving force of the eruption. The room of frescoes, for instance, will be on display along with plaster casts of the family who lived there. The bodies of a man, woman and small children huddled together in terror under the stairs of their house left uncanny impressions in the volcanic ash from which plaster casts were made. A dog rolling in agony on his back, one of the most famous of the casts, will also be part of the exhibition.

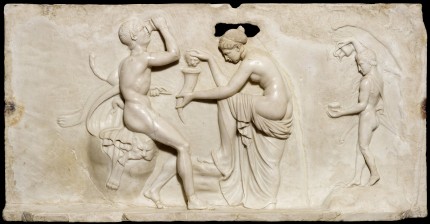

The two marble reliefs are part of a domestic scene from an elegant seaside villa in Herculaneum. They were embedded into two walls of a room whose fourth wall was open, overlooking the sea. There was probably a third matching relief on the third wall, but it was lost along with the wall during the eruption. The first one of the reliefs, a depiction of two satyrs and a mostly nude woman all engaged in the pouring and drinking of wine, was unearthed by accident in 1997.

The goal of the excavation was to uncover more of the Villa of the Papyri, a massive luxury home on the slopes of the volcano which belonged to Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, father of Calpurnia, wife of Julius Caesar. The Villa of the Papyri was named after the 1,785 carbonized papyrus scrolls found in the library during excavations by Swiss engineer Karl Weber in the second half of the 18th century. It was also the model for the Getty Villa in Los Angeles. It was excavated via tunnels cut through the volcanic rock and most of it remains undiscovered under the modern town. The 1997 attempt failed to find more of the Villa of the Papyri but the House of the Dionysiac Reliefs was no small consolation.

Excavations stopped because the parts of ancient Herculaneum that had already been exposed were in dire condition, so dire that much of the site had to be closed to tourists for their own safety. If this sounds familiar, it should. Pompeii is in the exact same position today. Herculaneum was saved by direct intervention of the privately funded Herculaneum Conservation Project (HCP) which focuses on doing all the constant maintenance necessary to keep an ancient archaeological site stable instead of digging for the next big, flashy find while the place falls apart around them.

Excavations stopped because the parts of ancient Herculaneum that had already been exposed were in dire condition, so dire that much of the site had to be closed to tourists for their own safety. If this sounds familiar, it should. Pompeii is in the exact same position today. Herculaneum was saved by direct intervention of the privately funded Herculaneum Conservation Project (HCP) which focuses on doing all the constant maintenance necessary to keep an ancient archaeological site stable instead of digging for the next big, flashy find while the place falls apart around them.

In 2009, the HCP turned its attentions to the House of the Dionysiac Reliefs to stabilize and conserve the excavated site. On the last day of the project, the mud caking a section of wall fell off and a second marble relief in even better condition than the first one saw the light of the day for the first time since 79 A.D. This panel depicts a dancing Maenad and a bearded man, probably Dionysius, facing each other on the right side while on the left two other figures stand before an archaic Greek sculpture of Dionysius.

Since it was found still embedded in the wall, archaeologists were given the rare opportunity to study how these panels were mounted. There was no mortar used. They were placed in a niche two inches deep and held in place with iron cramps, two on the long sides, one on the short sides. Once the panel was in place, the exposed edges were filled in with painted plaster. Greek-style reliefs were very popular among wealthy Romans in the 1st century A.D.; getting to explore the practical mechanics of their installation was of major archaeological significance.

The second panel has never been on display before, and the last time the two were seen by human eyes in the same room was August 24th (or November 23rd), 79 A.D. Your eyeballs can be next by going to see the exhibition which opens March 28th and closes September 29th. This is destined to be another blockbuster, so if you’re in London or planning to be there during those dates, book your tickets now.