A dozen hand-written sheets in a box of old solicitor’s records in Lichfield, a cathedral city in Staffordshire, England, bear surprising witness to women voting in a local election in 1843, 11 years after the Great Reform Act restricted the parliamentary franchise to “male persons,” 8 years after the Municipal Corporations Act forbade women from voting in town council elections, 26 years before the Municipal Franchise Act re-granted women taxpayers (later restricted to single women or widows) the vote in local council elections, and a full 75 years before the 1918 Representation of the People Act granted women over the age of 30 with qualifying property the right to vote in parliamentary elections and 85 years before women were given the same voting rights as men.

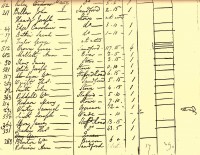

The pages come from a poll book, a list of voters, their domiciles, the value of their property, the number of votes they were allowed (the franchise was determined based on the payment of poor rates, a tax levied on the parish which was collected from heads of households who owned or rented property of qualifying value; the higher the rates, the more votes you got) and who they voted for. There was no secret ballot back then, and the voting lists were used much like survey responses, donor lists and possible voter lists are used by campaigns today.

The pages come from a poll book, a list of voters, their domiciles, the value of their property, the number of votes they were allowed (the franchise was determined based on the payment of poor rates, a tax levied on the parish which was collected from heads of households who owned or rented property of qualifying value; the higher the rates, the more votes you got) and who they voted for. There was no secret ballot back then, and the voting lists were used much like survey responses, donor lists and possible voter lists are used by campaigns today.

The record was compiled because the solicitors were the agents for the Conservative party in Lichfield. The town was a highly marginal constituency in this period, so the party clearly wanted to keep tabs on the political temperature between parliamentary elections. The solicitor would have compiled the poll book from the ballot papers returned by the voters.

There are 30 women listed out of 175 voters, an impressive percentage that indicates an involved female electorate. One woman, Grace Brown, a widowed butcher with a large household, was allowed four votes, all of which went to the Conservative candidate.

They aren’t all wealthy widows, though. University of Warwick Professor Sarah Richardson has researched the women on the list and found that in the 1841 census, two of the women were listed as paupers, one as a live-in servant, one as a washerwoman, one the wife of a dyer, another the wife of a sawyer. The presence of penurious women on the poll lists is perhaps an even greater surprise than the presence of women at all.

This election was for the local office of Assistant Overseer of the Poor in the parish of St. Chad’s, and although the 1832 reforms sought to regularize and codify local practices, the deeply rooted traditions of common law and custom surrounding the franchise could not be obliterated by parliamentary legislation. Administrative officers in parish elections, town commissioner elections, workhouse guardian elections, were run as they had been run. That’s why the Lichfield poor tax standard was applied to this election rather than the Municipal Corporations Act.

Historians have always known that women could vote in these types of elections, but until there hasn’t been any concrete evidence that they actually did. The closest we’ve got are very occasional references, not all of them serious, in the contemporary press to women voting in local elections, but an official poll book for a parish election of a significant administrative officer is a whole other animal. It is direct evidence of an active female vote.

The office’s name may seem modest, but in terms of real impact on people’s lives it was of major importance. The Overseers of the Poor collected the poor tax, so not only was this official a powerful person who could determine with great degree of discretion who received relief benefits, who had to go to the workhouse, who paid what tax, but in Lichfield, he also determined who got to vote for him. A vote for the Assistant Overseer of the Poor was a vote for someone who made life-and-death decisions. The fact that this was an elected position is notable in and of itself; Overseers of the Poor were appointed by local magistrates or boards of guardians in many places.

Richardson thinks the paupers may have paid their rates using their benefits money, thus affording the vote, but technically being recipients of out relief barred them from the vote. If that is what happened, it’s a remarkable cycle: the Overseer determines who gets benefits and who gets the vote based on the rates they pay, the women pay the rates from relief money so they can vote for the Overseer. It’s also possible that there were some shenanigans underpinning the pauper votes. Their votes could have been bought, the rates paid by a third party who then commanded them to vote for a certain candidate.

Another possibility is that they weren’t paupers anymore, that between the 1841 census and the 1843 election, they managed to scrounge up a household and pay legitimate poor rates. It’s unlikely (there wasn’t a great deal of upward mobility in this society) but it’s not impossible. Sarah Payne, the servant on the list, for example, lived with an elderly lady in 1841. She died and either left her property to her servant, or in some other way Payne was adjudicated the property-holder for the purposes of the poll book.

This discovery opens a new perspective into the complex history of the franchise, and will hopefully spur historians to dig up primary sources instead of taking for granted that proscriptive legislation translated into practices as restrictive as the law wanted them to be.

You can hear more from Sarah Richardson and other historians’ reactions to the find in this BBC Radio program. It’s 20 minutes long and eminently listenable.