Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) is leaving France for the first time since 1890 to go on display alongside her mentor, Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538), in an exhibition at the Doge’s Palace in Venice. Manet: Return to Venice will run from April 24th to August 11th. It celebrates the influence of Italian Renaissance art on Manet and will feature more than 80 paintings and drawings that showcase how Manet’s visits to Italy inspired his work throughout his life.

Manet’s pieces will be placed next to the Italian works associated with them, most notably Olympia and Venus of Urbino. Art historians often speak of the two works in the same breath since Manet deliberately and recognizably used the Renaissance masterpiece as the model for his own boundary-busting exploration of the female nude. They have never met in the proverbial and copious flesh, though, because Olympia belongs to the France since Claude Monet, who the raised funds to buy it after Manet’s death, donated it to the state in 1890. It’s such an important watershed in modern painting that none of the museums that have hosted it (the Musée du Luxembourg from 1890 to 1907, the Louvre from 1907 to 1986, and the Musée d’Orsay from 1986 until the present) have ever allowed it to travel. Venus of Urbino is in the permanent collection of the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence and Italian regulations prohibit it from leaving the country.

This one-of-a-kind pairing was only made possible through the D’Orsay’s special collaboration with the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. The French museum is loaning 42 of Manet’s works to the exhibit, an unprecedented number that will make up more than half the total pieces on display. Part of the motivation is fundraising as the D’Orsay will be making millions in loan fees, but museum president Guy Cogeval said, “It’s every art historian’s obsession to bring together these two great works of art, of which one served as a model for the other.”

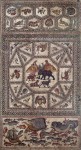

Indeed they have more than a reclining nude subject in common. They both scandalized viewers, Manet’s from its first exhibition at the Paris Salon in 1865, Titian’s for several hundred years. Venus of Urbino was the first female nude of the era to be depicted reclining and with her eyes on the viewer. It was commissioned by Guidobaldo della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, in 1534, possibly as an instructional for his 16-year-old wife. Its eroticism was intended for private display and remained in the family until 1637 when Vittoria della Rovere brought it to Florence after her marriage to Ferdinand II of Tuscany, father of Cosimo III and grandfather of Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici. The Venus was first placed in a public gallery in 1736, when Anna Maria had it placed in the Uffizi, but it was covered by an image of Sacred Love to keep it out of prurient view.

By the time Mark Twain visited the Uffizi in 1880, the Venus was no longer hidden, but it was still scandalous. Here’s how Twain described the painting in Chapter 50 of A Tramp Abroad:

You enter, and proceed to that most-visited little gallery that exists in the world — the Tribune — and there, against the wall, without obstructing rag or leaf, you may look your fill upon the foulest, the vilest, the obscenest picture the world possesses — Titian’s Venus. It isn’t that she is naked and stretched out on a bed — no, it is the attitude of one of her arms and hand.

He wasn’t being a prude so much as making a point about how explicit visual art was allowed to be even considering Victorian views towards public sexuality while anyone who described the Venus in words would be pilloried for obscenity, but he’s still shocked by the naked lady touching herself.

If I ventured to describe that attitude, there would be a fine howl — but there the Venus lies, for anybody to gloat over that wants to — and there she has a right to lie, for she is a work of art, and Art has its privileges. I saw young girls stealing furtive glances at her; I saw young men gaze long and absorbedly at her; I saw aged, infirm men hang upon her charms with a pathetic interest. How I should like to describe her — just to see what a holy indignation I could stir up in the world—just to hear the unreflecting average man deliver himself about my grossness and coarseness, and all that. The world says that no worded description of a moving spectacle is a hundredth part as moving as the same spectacle seen with one’s own eyes — yet the world is willing to let its son and its daughter and itself look at Titian’s beast, but won’t stand a description of it in words. Which shows that the world is not as consistent as it might be.

If Twain spluttered at Titian’s Venus of Urbino, by then 350 years old and a widely acknowledged masterpiece, critics went into full-on paroxysms over Manet’s Olympia when it debuted 15 years before Twain’s trip to Florence (a sound refutation of his contention that the visual arts got a pass when it comes to erotic content). Olympia was called every name in the book. Jules Claretie fulminated in Le Figaro: “What’s this yellow-bellied Odalisque, this vile model picked up who knows where, and who represents Olympia? Olympia? What Olympia? A courtesan, no doubt.” Viewers in the gallery flocked to express their hatred for it. Antonin Proust (no relation to Marcel), a journalist, politician and friend of Manet’s, wrote in his memoirs: “If the canvas of the Olympia was not destroyed, it is only because of the precautions that were taken by the administration,” namely hanging it far out of reach of canes. As Claretie put it, it was hung “at a height where even lousy paintings are never hung, above a gigantic door of the last room where it was hard to tell whether one was looking at a pile of naked flesh or a pile of linen.”

As it happens, Manet’s model was no courtesan but Victorine Meurent, who in addition to modeling for artists was a musician and painter in her own right. Titian’s, on the other hand, was. The model for Venus was Angela del Moro, a frequent dinner companion of Titian’s and the second-highest paid courtesan in Venice who was known for her refusal to fake orgasms. In the sensual environment of 16th century Venice, this was hardly a deficit.

As it happens, Manet’s model was no courtesan but Victorine Meurent, who in addition to modeling for artists was a musician and painter in her own right. Titian’s, on the other hand, was. The model for Venus was Angela del Moro, a frequent dinner companion of Titian’s and the second-highest paid courtesan in Venice who was known for her refusal to fake orgasms. In the sensual environment of 16th century Venice, this was hardly a deficit.

Manet was depicting Victorine as a courtesan, however, while Titian, despite the sexual suggestiveness of the recumbent nude with her hand between her legs, was not. Venus is an idealized nude, her gaze direct but dreamy and her head turned down, resting demurely against her shoulder. She holds a nosegay of red roses, symbol of love, in one hand and the other hand is delicately poised against her inner thigh, covering her vulva even as it draws attention to it. Her little sleeping dog is a symbol of marital fidelity, and the maid hovering protectively over the young girl who digs through through the bridal hope chest in the background is a symbol of motherhood.

Olympia shares none of Venus idealized features and she is depicted as a demimondaine or courtesan. She reclines on a disheveled bed on top of a silk shawl, an orientalist image of luxurious decadence, wearing an orchid, a symbol of sexuality, in her hair while at her feet the loyal dog is replaced by a black cat with her tail in the air, a symbol of prostitution. Her gaze is direct and unflinching. Her hand doesn’t brush against her vulva like Venus‘ but rather blocks our view of it. She shows no interest in the massive flower arrangement, probably from a wealthy client, her servant brings her.

Manet’s style, the flat perspective, the broad, quick brushstrokes, the strong color contrasts and lack of smooth shading, was probably a large part of the fury directed at this painting. He was doing something new, something the classicists of the age weren’t ready to cope with, but that today has garnered Manet the title of the first modern painter, precursor to the Impressionists who would follow him.