The carved outline of foot found on the removable deck planking of the late 9th century Viking Gokstad Ship bears mute witness to how at least one crew member passed the time during a long sea voyage. There are two foot outlines: a right foot carved across two planks and a weaker outline of a left foot on a single plank. The deck was made out of moveable pine planks that could easily be lifted if the crew needed to access the small hold for cargo storage or to bail out water. When the ship was first excavated in 1880, the planks were found scattered so we don’t know if the feet were originally next to each other or if they were carved independently.

The carved outline of foot found on the removable deck planking of the late 9th century Viking Gokstad Ship bears mute witness to how at least one crew member passed the time during a long sea voyage. There are two foot outlines: a right foot carved across two planks and a weaker outline of a left foot on a single plank. The deck was made out of moveable pine planks that could easily be lifted if the crew needed to access the small hold for cargo storage or to bail out water. When the ship was first excavated in 1880, the planks were found scattered so we don’t know if the feet were originally next to each other or if they were carved independently.

Even though the ship was excavated 133 years ago and has been in Oslo’s Viking Ship Museum since 1932, researchers only noticed the footprints in 2009 when moving the loose floorboards. Museum storage manager Hanne Lovise Aannestad thinks the carving was the work of a bored youth, much like kids these days might carve their initials into their desks.

“My guess is that some time or another a person was bored and simply traced his foot with his knife. It’s a kind of an ‘I was here’ message,” says Aannestad. […]

“My guess is that some time or another a person was bored and simply traced his foot with his knife. It’s a kind of an ‘I was here’ message,” says Aannestad. […]

Aannestad has measured one of her own feet against a tracing of the carved outline – because no one can actually step on the fragile floorboard, of course. The foot was smaller than hers, and even though people were generally shorter in the Viking days, this was probably a little person.

“It could have been a young man. People were treated as adults much earlier in those days. They took off sooner than we would allow young boys to do today,” says Aannestad.

They should add the shoe outline to the exhibit so visitors, especially kids, can compare their feet to that of a real Viking who lived and traveled in that ship 1100 years ago.

The foot carving is not the first time a young man established a lasting connection to this ship. It was first discovered on Gokstad farm near the town of Sandefjord on the west side of the Oslo Fjord in 1880 by the two teenage sons of the farm’s owner. The hill was called Kongshaugen (meaning “The King’s Mound”), and one day the boys decided to see if the legends that a king was buried there with all his treasure might be true. Just after New Year’s when the ground was still frozen, the highly motivated youths climbed the hill and started digging. Although the name suggests the hill was a burial mound for royalty, there are many mounds named Kongshaugen that turn out to be just hills. This one turned out to have an elaborate Viking ship burial within.

The news reached the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments and its then-president Nicolay Nicolayse managed to stop the amateur dig. He returned in the Spring and began a proper excavation from the side instead of the top down. You can read his 1892 account of the dig here. What he found was an oak clinker-built ship 76 feet long and 17 feet wide with 16 oar holes on each side of the hull. There was room for more than the 34 rowers, however. The ship’s maximum capacity was around 70. A scrap of white wool with red stripes sewn on was found in the front of the ship, possibly a fragment of the square sail.

The news reached the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments and its then-president Nicolay Nicolayse managed to stop the amateur dig. He returned in the Spring and began a proper excavation from the side instead of the top down. You can read his 1892 account of the dig here. What he found was an oak clinker-built ship 76 feet long and 17 feet wide with 16 oar holes on each side of the hull. There was room for more than the 34 rowers, however. The ship’s maximum capacity was around 70. A scrap of white wool with red stripes sewn on was found in the front of the ship, possibly a fragment of the square sail.

There was a birch bark-covered wooden burial chamber built at the stern of the ship behind the mast. Inside the burial chamber was a raised bed with the incomplete skeleton of an adult male, a man in his 40s around 5’9″ whose leg bones showed the marks of the cutting blows that probably killed him in battle. Blows to the leg were a common fighting technique in Viking times. Fragments of silk and gold thread stuck in the joists of the roof indicate the chamber was once draped with expensive textiles.

There were grave goods, although none of the gold, silver, jewelry, precious accessories and armaments that usually accompanied a Viking ship burial. Those had been looted, probably not long after the burial, but plenty of archaeological wonders remained: wooden furniture, a game board with horn pieces, fish hooks, a sledge, a tent, a harness tackle made of iron, lead and gilded bronze, fish hooks, kitchen equipment, six beds and 64 shields. There were also three smaller boats in pieces and the remains of many animals (eight dogs, two goshawks, two peacocks and 12 horses).

The ship and artifacts were removed to the University of Oslo where they were studied, conserved and stored until the Viking Ship Museum room was built to house them. Since this was before the days of PEG and giant freeze dryers, the wood dried during excavation and conservation. Restorers steamed the planks to shape them back into their original curved positions and put the ship back together. The wood that was too damaged to subject to the process was replaced with modern planks.

The ship and artifacts were removed to the University of Oslo where they were studied, conserved and stored until the Viking Ship Museum room was built to house them. Since this was before the days of PEG and giant freeze dryers, the wood dried during excavation and conservation. Restorers steamed the planks to shape them back into their original curved positions and put the ship back together. The wood that was too damaged to subject to the process was replaced with modern planks.

It wasn’t until 1993 that dendrochronological (tree ring) analysis narrowed down the date. The timber that built the ship was felled in 890. The ship was used for sea voyages for at least a decade — we know this because the oar ports in the upper hull are worn and now because smart-alecky teenagers carved their feet into the deck — before being retired for the burial of what had to be a very important person. A possible candidate for the deceased is Olaf Geirstad-Alf, a king of Vestfold of the Swedish Yngling dynasty, who according to the Norse saga Heimskringla died at the end of the 9th century.

Although the ship and grave contents have been much seen and analyzed since their discovery, the site itself has been somewhat neglected. As of 2009, researchers from the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo have returned to Gokstad to explore the mound in the light of our current understanding of Viking history and culture and using the latest technologies.

Up to now, the find has had an apparently isolated position, both as archaeological monument in the landscape, and as cultural historical phenomenon. Although sporadic archaeological investigations and chance finds since the 1880’s have demonstrated that the surroundings around Kongshaugen are rich in other contemporary structures, there has never been an attempt to investigate and analyze the landscape surrounding the mound as a whole. And likewise it has never been tried to look at the entire Gokstad find – the mound, the animals, the objects and the deceased – as a single, monumental manifestation by those who once created it, and to decipher what it was that they intended to accomplish. At the core of the Gokstad revitalised project thus stands the goal to create a context around the burial, and to give an archaeological answer to the question Who was the Gokstad man?

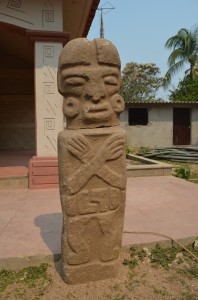

The statue was discovered in the north section of the town on the grounds of the biggest ball game pitch, an L-shaped court about 130 feet long. There are five ball courts in Piedra Labrada. Around twenty sculptures of snake heads, shells and anthropomorphic figures were found in three of them, but this is the first sculpture found in the north field and the only one that depicts a ball player.

The statue was discovered in the north section of the town on the grounds of the biggest ball game pitch, an L-shaped court about 130 feet long. There are five ball courts in Piedra Labrada. Around twenty sculptures of snake heads, shells and anthropomorphic figures were found in three of them, but this is the first sculpture found in the north field and the only one that depicts a ball player.