On March 21st, 2013, the Connecticut Historical Society acquired a collection of 91 letters written by Charlotte Cowles, a young girl from Farmington, Connecticut, to her brother Samuel between 1833 and 1846, and three letters from Samuel to Charlotte. With a final cost of $66,000 including buyer’s premium, this was a major purchase, requiring contributions from Farmington Historical Society, Farmington Bank as well as private donors. The reason these letters are worth tens of thousands of dollars is they include beautifully detailed accounts of the Mende captives who overthrew their Spanish captors on the ship La Amistad.

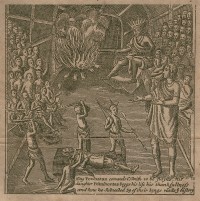

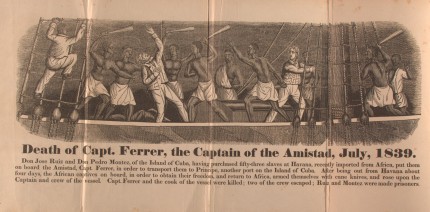

In 1839, 54 captives, 50 adults and four children, were kidnapped in what is today Sierra Leone and taken to Havana, Cuba, aboard the slave ship Tecora. The international slave trade had been outlawed by this point, with Great Britain, Spain and the United States all signatories to various treaties abolishing it. According to Spanish law, as soon as the captives landed in Cuba, they were free, but their captors fraudulently claimed they were Cuban-born slaves and sold them to local plantation owners. The Mende were loaded onto the schooner La Amistad headed for a sugar plantation in Puerto del Principe, Cuba.

Before they reached their destination, the captives, led by Sengbe Pieh, aka Joseph Cinqué, broke free and took control of the ship, killing some of the crew and demanding the survivors take them back home. Ship navigator Don Pedro Montez agreed, but instead steered the ship north along the east coast of the United States. As Montez had hoped, La Amistad was intercepted by a United States Revenue Cutter Service ship on the eastern point of Long Island. Hoping to claim the men under the admiralty salvage law, Lt. Thomas R. Gedney, commander of the revenue cutter, took the Mende to Connecticut where slavery was still technically legal (it was illegal in New York).

The Africans were imprisoned in New Haven, Connecticut, while their case went to court. It was a complex case with many interested parties from Gedney to the plantation owners to the captives themselves who insisted they were nobody’s property. The case was decided in the kidnapped Africans’ favor by a federal district court in 1840, and the decision was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court the next year. On March 9, 1841, the Supreme Court ruled that the Mende were free and should be allowed to go home.

The Africans were imprisoned in New Haven, Connecticut, while their case went to court. It was a complex case with many interested parties from Gedney to the plantation owners to the captives themselves who insisted they were nobody’s property. The case was decided in the kidnapped Africans’ favor by a federal district court in 1840, and the decision was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court the next year. On March 9, 1841, the Supreme Court ruled that the Mende were free and should be allowed to go home.

This is the point where Charlotte Cowles steps into the picture. Charlotte’s father Horace Cowles was a conductor on the Farmington Underground Railroad and an active abolitionist. When the Africans were released, Cowles and other abolitionist leaders known as the Amistad Committee who had helped with the legal defense hosted the Amistad captives in their homes. While they raised money to fund their return to Sierra Leone, the Committee members taught the Africans to speak and read English and attempted to convert them to Christianity.

Charlotte’s letters to her brother begin when she is just 13 years old. As she grows up, her writings expand from fabric and friends to an increasing abolitionist social consciousness. Her brother becomes editor of The Charter Oak, a Connecticut abolitionist newspaper, and Charlotte co-founds the Farmington Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. By 1838, she is fully involved in abolitionist causes, telling her brother about the passengers on the Underground Railroad staying at their house on their way to Canada.

When the Amistad Africans were released, the Cowles family hosted one of the children, a girl named Te-meh which Charlotte spells Tenyeh. It takes the Amistad Committee a year to raise the money for the return trip and during that year Charlotte tells her brother all about her guest and the rest of the Mende. From a letter written April 8th, 1841:

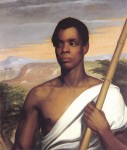

Cinque is as choice of his dignity as ever, yet he is often very affable, but none of them are so easy to converse with as Kinna because he speaks English so much more fluently — He is so modest and gentle too, and every one thinks him very fine-looking. Little Fouli is all animation and yet so timid, and little Ka-le is so very bright, and Ya-bo-i is so full of good humor. — I do not know how to say enough about any of them. But Mary’s and my principal favorite, just now at least, is one whom I never heard mentioned. His name is sometimes spelled Ba-gua, but it is entirely unpronounceable, so we call it Banyeh. He is about eighteen, and the most splendid specimen of African beauty I ever saw. I have read in books of this style of beauty, but I never before believed it possible for an African to be very handsome. But if any one sees no beauty in his beaming face and sparkling eyes, all I can say is that their prejudices are control their whole souls and even their fancies. If he were painted for an Othello, the whole beau monde would be delighted. The most remarkable thing about him however is a certain dashing elegance of manner which none of the others possess at all—which is indeed the rarest accomplishment in the most polished society. […]

After all, can you begin to realize that these interesting creatures are but a very small specimen of the victims which the merciless slave- trade is every week—now, this very moment — seizing and destroying! The idea of Cinque and Kinna and Banyeh toiling on a plantation seems incredible. I feel that I never had the least conception before of the horrors of that accursed business, or of the mass of misery that exists in this world; and now, how inadequate!

I could quote the whole letter because every line is an eye-opening record of the Amistad refugees and of abolitionist society. The whole collection is a unique glimpse into the life of a young girl in 1830s Connecticut who grapples with the most quotidian things to issues so huge that 20 years later they would tear the country apart. Even the smallest details — like how hard it is for Charlotte to get to Hartford, which is just 10 miles away from Farmington, to purchase the red and burgundy striped fabric she wants — are fascinating.

The letters are now on display at the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford. The exhibition opened on June 19th in celebration of Juneteenth, a holiday commemorating of the end of slavery in Texas on June 19th, 1865, and features the original letters and transcripts. Scans of the letters and slightly annoyingly formatted transcripts (every other word is underscored as a search keyword) have also been uploaded to Connecticut History Online. Search for “Charlotte Cowles” to see them all.