Archaeologists excavating the ancient Mayan site of Holmul in the northeastern Guatemalan region of El Petén have discovered a monumental high-relief frieze buried in the foundations of a temple pyramid. The part of the temple in which the frieze was built in 590 A.D., a turbulent and poorly documented period in which the rulers of Tikal fought for control of the area with the Snake dynasty of Calakmul (the variant Kaanul is used in some articles about the find). The pyramid was built over it in the 8th century.

Lead archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli was excavating a tunnel dug by looters looking for remains from the Maya Preclassic period (2,000 B.C. – 250 A.D.), the area he specializes in. He extended the tunnel just a little ways past the point where the looters gave up and found the frieze. It’s from the Classic Maya period, but Estrada-Belli was far from disappointed.

Lead archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli was excavating a tunnel dug by looters looking for remains from the Maya Preclassic period (2,000 B.C. – 250 A.D.), the area he specializes in. He extended the tunnel just a little ways past the point where the looters gave up and found the frieze. It’s from the Classic Maya period, but Estrada-Belli was far from disappointed.

“It is one of the most fabulous things I have ever seen,” says archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli of the Holmul Archaeological Project. “The preservation is wonderful because it was very carefully packed with dirt before they started building over it.”

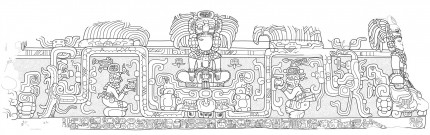

It’s 26 feet wide, 6 feet high fully 95% of the carving is intact (only the one corner closest to the surface is eroded). There are even traces of the original polychrome paint still visible. Three human figures, one on each end and one in the middle, wear feather headdresses and jade jewels. Each man is identified by a cartouche, but only the name of the central figure is still legible: Och Chan Yopaat, meaning “the storm god enters the sky.” The three men are seated cross-legged over the head of a mountain spirit. Beneath Och Chan Yopaat, two feathered serpents emerge from the mountain spirit. They too are sacred spirits emanating from the mouth of the mountain which is the ancestral home of the ruling Holmul dynasty. The serpents frame two deities who hold signs in both hands that read “naaah waaj” meaning “first tamale,” a reference to a ceremonial food offering.

Underneath the figures is a band of 30 glyphs dedicating the building to Ajwosaj Chan K’inich, ruler of Naranjo, a city-state south of Holmul allied to the Snake Lords of Calakmul. The inscription describes Ajwosaj’s involvement in Holmul in an usual way. The glyph for a verb that means “to put in order” is followed by the name of a local deity archaeologists believe may have been a patron god linked to the Snake dynasty. Estrada-Belli believes this passage describes a ritual re-establishment of a local god who had been ousted by the Tikal rulers when they conquered Holmul.

Putting it all together, Estrada-Belli thinks Ajwosaj, fighting under the Snake Lord banner, defeated the Tikal allies who ruled Holmul and installed Och Chan Yopaat as a ruler allied to Calakmul via Naranjo. Ajwosaj also returned the ancestral deities displaced by Tikal to their rightful place and the frieze depicts this ceremony. This is the first time Och Chan Yopaat has appeared in the historical record, and before now historians didn’t know which of the two dominant powers ruled Holmul in this period.

As if the frieze with its precious new information about Maya history weren’t enough, the team also found the remains of an adult male buried beneath the steps leading to the building the frieze decorates. He was buried with ceramic offerings depicting, among other religious icons, the nine gods of the Maya underworld. One incisor and a canine had been drilled and filled with jade beads. Jade is a symbol of royalty in Mayan culture. The remains of a decayed wooden mask were found on his chest. There is no handy cartouche identifying him, but it’s possible that he’s one of the figures from the frieze. He’s certainly a member of the ruling class. A large hieroglyphic symbol carved on the side of the frieze building marks it as a royal house probably dedicated to deified local rulers.

As if the frieze with its precious new information about Maya history weren’t enough, the team also found the remains of an adult male buried beneath the steps leading to the building the frieze decorates. He was buried with ceramic offerings depicting, among other religious icons, the nine gods of the Maya underworld. One incisor and a canine had been drilled and filled with jade beads. Jade is a symbol of royalty in Mayan culture. The remains of a decayed wooden mask were found on his chest. There is no handy cartouche identifying him, but it’s possible that he’s one of the figures from the frieze. He’s certainly a member of the ruling class. A large hieroglyphic symbol carved on the side of the frieze building marks it as a royal house probably dedicated to deified local rulers.

The tunnel leading to the frieze has been reburied for now to keep the find safe from the looters who just missed it last time and to keep the humidity and temperature as stable as possible. Work on the site has stopped now as the rainy season approaches, but it is being monitored for security purposes. Estrada-Belli hopes they can eventually stabilize the site enough that it can be visited by tourists, but that’s a long-term goal. In the short term, he’s just hoping the frieze will be unharmed and ready for more study when the team returns next Spring.