A fragment of cloth from a flag the flew over the Battle of Bosworth on August 22, 1485, sold to an anonymous private collector for £3,800 ($6,150) at auction last Saturday. The 6.5-inch by 5.5-inch piece of gold and red fabric is a remnant of the standard of Henry Tudor, who after his victory over King Richard III at Bosworth would become King Henry VII. From the auction house press release:

A fragment of cloth from a flag the flew over the Battle of Bosworth on August 22, 1485, sold to an anonymous private collector for £3,800 ($6,150) at auction last Saturday. The 6.5-inch by 5.5-inch piece of gold and red fabric is a remnant of the standard of Henry Tudor, who after his victory over King Richard III at Bosworth would become King Henry VII. From the auction house press release:

The fragment had been passed around over the years as an amusing after-dinner thought,” [auctioneer Charles Hanson] said.

“Our vendors are obviously aware of its social value today since the imagination of what happened at the Battle of Bosworth will keep historians debating for years to come. I am just delighted such a fundamental accessory to that 1485 battle has been unearthed only months after finding King Richard III in a Leicester car park. As an auctioneer, I thrive on the social relevance such bygone artefacts had on society. If only this fragment could talk I am sure it could tell us so much.”

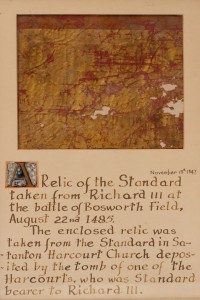

The flag fragment is mounted in a frame along with a description of its history dated November 13, 1847. It’s been in the same family ever since then. Doubtless the result of 400 years of oral transmission, aka a very long game of telephone, the description gets some key facts wrong. It claims the piece is:

The flag fragment is mounted in a frame along with a description of its history dated November 13, 1847. It’s been in the same family ever since then. Doubtless the result of 400 years of oral transmission, aka a very long game of telephone, the description gets some key facts wrong. It claims the piece is:

A relic of the Standard taken from Richard III at the battle of Bosworth Field, August 22, 1485. The enclosed relic was taken from Standard in Stanton Harcourt Church deposited by the tomb of one of the Harcourts, who was the Standard bearer to Richard III.

The glaring inaccuracy in this account is whose standard the fragment came from since we know it to be Henry Tudor’s rather than his royal opponent’s. The piece was taken from the Bosworth flag hung over the tomb of Henry’s standard bearer, Sir Robert Harcourt, Knight of The Bath. Sir Robert died five years after the battle, around 1490, and was buried in the Harcourt Chapel in St Michael’s Church, Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire. The tattered remains of the standard he bore were hung above his effigy.

The glaring inaccuracy in this account is whose standard the fragment came from since we know it to be Henry Tudor’s rather than his royal opponent’s. The piece was taken from the Bosworth flag hung over the tomb of Henry’s standard bearer, Sir Robert Harcourt, Knight of The Bath. Sir Robert died five years after the battle, around 1490, and was buried in the Harcourt Chapel in St Michael’s Church, Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire. The tattered remains of the standard he bore were hung above his effigy.

Across from his tomb is that of his grandfather, also named Sir Robert Harcourt, and his wife Margaret Byron. The elder Sir Robert was initially a Lancastrian with a front row seat to the inception of the War of the Roses. He escorted Margaret of Anjou from France to England in 1445 to marry King Henry VI. Things began to go south in 1448 when he killed fellow Lancastrian Richard Stafford at Coventry. He was pardoned for killing Stafford by the king in 1450, but the murder launched a feud between the families that would last for 38 years, long outliving Robert.

As a result of the feud, Harcourt’s Lancastrian loyalties were sorely tested. He was already suspected of having Yorkist sympathies in 1459 and by 1463 he was a confirmed Yorkist. King Edward IV made him a Knight of the Garter that year and he fought for Edward in the siege of Alnwick Castle. For his great services in the capture of Alnwick, Robert was granted £300 a year for life. He died on November 14th, 1470, at the hands of a bastard son of William Stafford of Grafton and 150 Stafford retainers.

As a result of the feud, Harcourt’s Lancastrian loyalties were sorely tested. He was already suspected of having Yorkist sympathies in 1459 and by 1463 he was a confirmed Yorkist. King Edward IV made him a Knight of the Garter that year and he fought for Edward in the siege of Alnwick Castle. For his great services in the capture of Alnwick, Robert was granted £300 a year for life. He died on November 14th, 1470, at the hands of a bastard son of William Stafford of Grafton and 150 Stafford retainers.

By 1485, the Harcourts were Lancastrian again, now fighting on Henry Tudor’s side. The Staffords took the other side and fought for Richard at Bosworth. The next year, Sir Humphrey Stafford of Grafton and his brother Thomas co-led the first uprising against King Henry VII after Bosworth, conspiring with Francis Lovell, 1st Viscount Lovell. The Stafford and Lovell Rebellion was quickly suppressed. The Staffords picked a fight in Worcester which was a stronghold of support for Henry, while Lovell thought better of putting his neck on the line and fled to Burgundy. The Staffords took cover in a monastery from which Henry removed them by force, engendering a big brouhaha about the right of sanctuary that resulted in a Papal Bull that excluded sanctuary entirely in cases of treason. Thomas Stafford was pardoned. Humphrey Stafford was executed at Tyburn. The feud between the Harcourts and the Staffords died with him.

By 1485, the Harcourts were Lancastrian again, now fighting on Henry Tudor’s side. The Staffords took the other side and fought for Richard at Bosworth. The next year, Sir Humphrey Stafford of Grafton and his brother Thomas co-led the first uprising against King Henry VII after Bosworth, conspiring with Francis Lovell, 1st Viscount Lovell. The Stafford and Lovell Rebellion was quickly suppressed. The Staffords picked a fight in Worcester which was a stronghold of support for Henry, while Lovell thought better of putting his neck on the line and fled to Burgundy. The Staffords took cover in a monastery from which Henry removed them by force, engendering a big brouhaha about the right of sanctuary that resulted in a Papal Bull that excluded sanctuary entirely in cases of treason. Thomas Stafford was pardoned. Humphrey Stafford was executed at Tyburn. The feud between the Harcourts and the Staffords died with him.

In an unrelated but nonetheless satisfying coincidence, the Harcourt family, Norman French descendants of the Viking yarl Bernard the Dane, fought with William the Conqueror and settled in England after the Battle of Hastings. William granted them estates in Leicestershire and they made their family seat in, you guessed it, Bosworth. The family seat only moved to Oxforshire in 1191 when yet another Robert de Harcourt inherited the Stanton manor from his wife Isabel de Camville’s father. The town of Stanton was then renamed to Stanton Harcourt and the Harcourts have been there ever since. They still own the manor house although it hasn’t been the family seat since the 19th century.