A musical pig credited with saving the life of its owner, Edith Rosenbaum, during the sinking of the Titanic on April 14th, 1912, has been silent for decades. Now, thanks to the wonders of technology, the pig’s song can be heard again.

Edith (she would legally change her last name to Russell in 1918 out of concern about anti-German sentiment in the wake of World War I) was a fashion writer for Women’s Wear Daily, one of the first professional stylists with a glittering roster of show business clients on both sides of the Atlantic and had her own fashion label “Elrose” carried exclusively by Lord & Taylor’s. She was 32 and at the peak of her professional success when she boarded Titanic at Cherbourg. She booked a first class cabin for herself and the 19 trunks full of glamorous gowns she was bringing across the ocean for her American clients.

Edith (she would legally change her last name to Russell in 1918 out of concern about anti-German sentiment in the wake of World War I) was a fashion writer for Women’s Wear Daily, one of the first professional stylists with a glittering roster of show business clients on both sides of the Atlantic and had her own fashion label “Elrose” carried exclusively by Lord & Taylor’s. She was 32 and at the peak of her professional success when she boarded Titanic at Cherbourg. She booked a first class cabin for herself and the 19 trunks full of glamorous gowns she was bringing across the ocean for her American clients.

When the iceberg hit, Edith was unconcerned. In British Pathé interview from 1970, she describes people making snowballs out of the ice shards left on the deck after the collision. When a cabin steward told her it was time to abandon ship, she locked all 19 of her trunks and put all 19 keys in her pocket. One thing she kept with her: her lucky musical pig which she had gotten after a serious car accident the year before in which the driver had died.

She did not want to leave the ship. The lifeboats weren’t attached to the deck so you could just step into them. There was an intimidating gap between the ship and the boats, and they were in various states of being lowered to the ocean. People had to climb up on the railing and jump into the boats. If they missed, all that awaited them was a 14-storey plunge into freezing water. Edith preferred to stay put. A sailor saw her and intervened. He said: “You don’t want to be saved; well, I’ll save your baby.” He snatched the pig out from under her arm and dropped into Lifeboat 11. In the interview Edit says “when they threw that pig, I knew it was my mother calling me.” She jumped in after him, and that’s how the pig saved her life.

She did not want to leave the ship. The lifeboats weren’t attached to the deck so you could just step into them. There was an intimidating gap between the ship and the boats, and they were in various states of being lowered to the ocean. People had to climb up on the railing and jump into the boats. If they missed, all that awaited them was a 14-storey plunge into freezing water. Edith preferred to stay put. A sailor saw her and intervened. He said: “You don’t want to be saved; well, I’ll save your baby.” He snatched the pig out from under her arm and dropped into Lifeboat 11. In the interview Edit says “when they threw that pig, I knew it was my mother calling me.” She jumped in after him, and that’s how the pig saved her life.

She played the musical pig to soothe the children on the lifeboat. One of those children was Philip Aks, a baby who was just 10 months old. He had been separated from his 18-year-old mother, third-class passengers Leah Aks, during the chaos. He was thrown into Lifeboat 11 while his mother was forced into the next boat even though she tried to push her way onto 11 to be with her son. Edith held little Philip and played the music for him over and over again. In April of 1953, Edit, Leah and Philip met again at a special preview of the movie Titanic starring Barbara Stanwyck. Producers invited a number of survivors who had an emotional reunion at the screening. Edit remarked: “The baby, amongst other babies, for whom I played my little pig music box to the tune of ‘Maxixe’ was there.” He is forty-one years old, is a rich steel magnate from Norfolk, Virginia.”

Russell was more directly involved in the next Titanic movie, the 1958 classic A Night to Remember. She basically forced herself onto producer William MacQuitty as an informal consultant for the picture. She had already introduced herself to Walter Lord, author of the book on which the movie was based, after his account became a best-seller. Edith had written a memoir of her own, the excellently named A Pig and a Prayer Saved Me from the Titanic, and she was angry that Lord had stolen her thunder with his well-received book. Lord was kind to her — he had been in contact with survivors in the process of researching the book but had been unable to find her — and they became friends. After her death in April 1975 at the venerable age of 96, Edith left her pig and other memorabilia to Walter Lord.

Russell was more directly involved in the next Titanic movie, the 1958 classic A Night to Remember. She basically forced herself onto producer William MacQuitty as an informal consultant for the picture. She had already introduced herself to Walter Lord, author of the book on which the movie was based, after his account became a best-seller. Edith had written a memoir of her own, the excellently named A Pig and a Prayer Saved Me from the Titanic, and she was angry that Lord had stolen her thunder with his well-received book. Lord was kind to her — he had been in contact with survivors in the process of researching the book but had been unable to find her — and they became friends. After her death in April 1975 at the venerable age of 96, Edith left her pig and other memorabilia to Walter Lord.

Lord died in 2002 and, as he was encouraged to do by fellow Titanic obsessive William MacQuitty, he bequeathed his vast collection of Titanic artifacts, many of them given to him by survivors, to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London. In 2003 the musical pig, the clothes Edith Russell had worn the night of the sinking and her unpublished manuscript of A Pig and a Prayer Saved Me from the Titanic, went on display as part of the permanent collection of the museum.

Lord died in 2002 and, as he was encouraged to do by fellow Titanic obsessive William MacQuitty, he bequeathed his vast collection of Titanic artifacts, many of them given to him by survivors, to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London. In 2003 the musical pig, the clothes Edith Russell had worn the night of the sinking and her unpublished manuscript of A Pig and a Prayer Saved Me from the Titanic, went on display as part of the permanent collection of the museum.

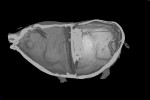

Last year, the pig was part of Titanic Remembered, the National Maritime Museum’s exhibition in honor of the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. Before the artifacts were returned to their permanent display in the museum’s Voyagers gallery, the pig and another artifact (the 18-carat gold pocket watch of passenger Robert Douglas Norman who sadly did not survive the sinking) were taken to the Nikon Metrology factory in Hertfordshire which has high resolution X-ray equipment used to analyze the minutiae of computer chips and other complex internal mechanisms.

Using X-ray computed tomography, the artifacts were scanned in three dimensions and a 3D model created from the scans. That model can then be broken apart, dissected and examined from every conceivable angle. Inside the pig researchers found its curly tail, long thought lost, and the crank-handle that was turned to make the music play. A loose pin was also inside the pig, possibly a relic of an attempt to activate the player after the crank-handle wound up in its rotund belly.

Using X-ray computed tomography, the artifacts were scanned in three dimensions and a 3D model created from the scans. That model can then be broken apart, dissected and examined from every conceivable angle. Inside the pig researchers found its curly tail, long thought lost, and the crank-handle that was turned to make the music play. A loose pin was also inside the pig, possibly a relic of an attempt to activate the player after the crank-handle wound up in its rotund belly.

The 3D models revealed the musical mechanism inside the pig. It’s a small, simple device with a toothed wheel turned by the crank shaft against a comb that reads the teeth as notes. It looks like those cylinders in player pianos except they’re perforated rather than toothy. Using the detailed images from the model, experts spent almost a year studying the mechanism and were able to piece together every note it once played. For the first time in living memory, hear the pig play the song that soothed the children on Lifeboat 11 while they waited in the frigid night for seven hours for the Carpathia to rescue them:

The 3D models revealed the musical mechanism inside the pig. It’s a small, simple device with a toothed wheel turned by the crank shaft against a comb that reads the teeth as notes. It looks like those cylinders in player pianos except they’re perforated rather than toothy. Using the detailed images from the model, experts spent almost a year studying the mechanism and were able to piece together every note it once played. For the first time in living memory, hear the pig play the song that soothed the children on Lifeboat 11 while they waited in the frigid night for seven hours for the Carpathia to rescue them:

According to Edith, the melody was the Maxixe, a popular Brazilian dance song, but the National Maritime Museum researchers challenged the Internet to name that tune. The Internet came through, bless its nerdy heart, and museum experts confirmed that it’s La Sorella, a march composed by Charles Borel-Clerq in 1905. The song is also known as La Matchiche, so Edith was right too.

The pig will be back on permanent display next week. He’ll be sporting his original knotted vellum tail which conservators were able to recover from inside the piggy and reattach it in its original position.