In 1944, an Australian soldier named Morry Isenberg was manned a radar station on the remote Wessell Islands in Australia’s Northern Territory looking out for approaching Japanese aircraft. The enemy planes never materialized, but Isenberg’s sharp eye did spot something else. While fishing on the shore of Marchinbar Island, he found nine coins. He pocketed them, wisely drew a map where X literally marked the find spot and then forgot about them for 35 years.

In 1944, an Australian soldier named Morry Isenberg was manned a radar station on the remote Wessell Islands in Australia’s Northern Territory looking out for approaching Japanese aircraft. The enemy planes never materialized, but Isenberg’s sharp eye did spot something else. While fishing on the shore of Marchinbar Island, he found nine coins. He pocketed them, wisely drew a map where X literally marked the find spot and then forgot about them for 35 years.

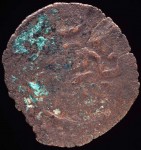

In 1979, Isenberg found the coins he’d stashed away and took them to experts to determine their origin and value. They determined four of the coins were minted by the Dutch East India Company in the 17th and 18th century, which is not unexpected since the first known European to reach Australia was Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon in 1606. The other five were the shockers: copper coins from the east African Kilwa Sultanate that date to around 1100.

In 1979, Isenberg found the coins he’d stashed away and took them to experts to determine their origin and value. They determined four of the coins were minted by the Dutch East India Company in the 17th and 18th century, which is not unexpected since the first known European to reach Australia was Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon in 1606. The other five were the shockers: copper coins from the east African Kilwa Sultanate that date to around 1100.

Before this, only one Kilwa coin has ever been found outside of the Swahili Coast (today the Indian Ocean coasts of Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique) where Kilwa dominated from 900 until the Portuguese broke up the sultanate in the early 1500s, and that coin was in Oman on the southeast Arabian peninsula. Oman was also colonized by the Portuguese for a few decades while they were in the neighborhood in the early 16th century and in the late 17th century Oman conquered the east African coast where Kilwa once reigned. So there were plenty of opportunities for an old Kilwa copper to wind up in Oman. How five of the made their way more than 6000 miles east to the Wessell Islands is a fascinating historical mystery, one with the potential to rewrite the history of when non-indigenous people first stepped foot in Oz.

Before this, only one Kilwa coin has ever been found outside of the Swahili Coast (today the Indian Ocean coasts of Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique) where Kilwa dominated from 900 until the Portuguese broke up the sultanate in the early 1500s, and that coin was in Oman on the southeast Arabian peninsula. Oman was also colonized by the Portuguese for a few decades while they were in the neighborhood in the early 16th century and in the late 17th century Oman conquered the east African coast where Kilwa once reigned. So there were plenty of opportunities for an old Kilwa copper to wind up in Oman. How five of the made their way more than 6000 miles east to the Wessell Islands is a fascinating historical mystery, one with the potential to rewrite the history of when non-indigenous people first stepped foot in Oz.

Kilwa is a small island off the coast of Tanzania. The sultanate was founded around 900 A.D. by displaced Persian prince Ali ibn al-Hassan Shirazi and soon became the primary center of commerce and trade on the east African coast. Kilwa territory grew nothing but coconut palms. They built their wealth as middlemen, trading manufactured goods from Arabia and India for food, gold and ivory with the inland Bantu communities, keeping the food and shipping the precious materials to Asia where they bought manufactured goods and started the cycle all over again. The Kilwa traders had sailing ships — coconut wood dhows sewn together with cocoa coir and sporting braided coconut leaf mat sails — that could travel as far as India during monsoon season thanks to propitious winds in the summer and then head back home in the winter. As far as we know, however, the Kilwa dhows couldn’t handle the turbulent waters and winds much further south than Inhambane, in today’s Mozambique.

Kilwa is a small island off the coast of Tanzania. The sultanate was founded around 900 A.D. by displaced Persian prince Ali ibn al-Hassan Shirazi and soon became the primary center of commerce and trade on the east African coast. Kilwa territory grew nothing but coconut palms. They built their wealth as middlemen, trading manufactured goods from Arabia and India for food, gold and ivory with the inland Bantu communities, keeping the food and shipping the precious materials to Asia where they bought manufactured goods and started the cycle all over again. The Kilwa traders had sailing ships — coconut wood dhows sewn together with cocoa coir and sporting braided coconut leaf mat sails — that could travel as far as India during monsoon season thanks to propitious winds in the summer and then head back home in the winter. As far as we know, however, the Kilwa dhows couldn’t handle the turbulent waters and winds much further south than Inhambane, in today’s Mozambique.

Ian McIntosh, an Australian archaeologist who is now an anthropology professor of at Indiana University, explored the island when he was writing his doctorate on the Wessel Islands in the 1990s, but there wasn’t the interest or funding to do a proper archaeological excavation. Interest in the coins’ story grew in 1998 after the wreck of an Arabian dhow was discovered off the island of Belitung on the east coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The wreck was laden with 60,000 Chinese Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 A.D.) artifacts including gold, silver and ceramics. The date of the wreck was determined by a handy date of manufacture on one of the ceramic bowls: 826 A.D.

Ian McIntosh, an Australian archaeologist who is now an anthropology professor of at Indiana University, explored the island when he was writing his doctorate on the Wessel Islands in the 1990s, but there wasn’t the interest or funding to do a proper archaeological excavation. Interest in the coins’ story grew in 1998 after the wreck of an Arabian dhow was discovered off the island of Belitung on the east coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The wreck was laden with 60,000 Chinese Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 A.D.) artifacts including gold, silver and ceramics. The date of the wreck was determined by a handy date of manufacture on one of the ceramic bowls: 826 A.D.

Despite the significant find, it wasn’t until this July that McIntosh was able to return to the Wessell Islands with a team sponsored by the Australian Geographic Society to do a proper archaeological investigation of the site. Oral tradition from the local Yolngu people tells many stories of men from distant lands touching down. The team went looking for any signs of a non-indigenous presence on the island: ballast rocks, ship remains, more African coins, etc.

Despite the significant find, it wasn’t until this July that McIntosh was able to return to the Wessell Islands with a team sponsored by the Australian Geographic Society to do a proper archaeological investigation of the site. Oral tradition from the local Yolngu people tells many stories of men from distant lands touching down. The team went looking for any signs of a non-indigenous presence on the island: ballast rocks, ship remains, more African coins, etc.

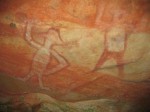

They didn’t find any more coins, but they did find something of great potential significance: indigenous rock paintings depicting a variety of ships and men wearing hats and trousers. The team documented about 20 images. Some feature whales and other local critters. Ten are ships of different sizes, shapes and configurations. One of them is a steamship with a visible propeller which obviously post-dates Captain Cook but is nonetheless a great find because it’s the only known rock art steamship. Another is a French sailing ship identifiable from its unique rigging.

They didn’t find any more coins, but they did find something of great potential significance: indigenous rock paintings depicting a variety of ships and men wearing hats and trousers. The team documented about 20 images. Some feature whales and other local critters. Ten are ships of different sizes, shapes and configurations. One of them is a steamship with a visible propeller which obviously post-dates Captain Cook but is nonetheless a great find because it’s the only known rock art steamship. Another is a French sailing ship identifiable from its unique rigging.

The find site was a challenge to rediscover because the surveyor’s map from 1944 didn’t match where the radar base was known to be. The team was eventually able to pinpoint the X spot thanks to some topographical features and the remains of oil drums and shell casings from World War II.

“We didn’t find more coins which is disappointing,” Dr McIntosh said. “But the location was very interesting. It’s in a very inhospitable little bit of territory, on this crocodile infested creek littered with flotsam and jetsam amid thick mangroves.”

The coins were clearly not from an old aboriginal settlement, he said, but were most likely part of the detritus washed into the mangrove from the sea.

“There can be only two conclusions, we think: One that they were a product of a storm surge from a shipwreck, and two, alternatively, they were in the possession of one person who just happened to lose them there for whatever reason.”

The team also discovered a piece of timber that at first glance looked like driftwood but upon closer examination appears to be deck bracing for a sailing ship. The wood hasn’t been dated yet, but it might be evidence of a relevant shipwreck.

The team also discovered a piece of timber that at first glance looked like driftwood but upon closer examination appears to be deck bracing for a sailing ship. The wood hasn’t been dated yet, but it might be evidence of a relevant shipwreck.

The timber and rock art will be thoroughly analyzed over the upcoming year. Next summer the expedition will return with underwater archaeologists who will dive the reefs looking for the remains of any ships that may have inspired the paintings.