During construction of a new road on the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson last year, workers unearthed multiple graves containing deceased residents of the Mississippi State Insane Asylum, a state hospital built in 1855 and closed in 1935. Between November and March, crews digging out the subsoil to make sure it was solid enough to support the road unearthed 66 bodies in pine boxes. The coffins were about six feet long, as you would expect, but much thinner than normal human width because they were compressed by the weight of the soil. There were no grave markers identifying the burials.

During construction of a new road on the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson last year, workers unearthed multiple graves containing deceased residents of the Mississippi State Insane Asylum, a state hospital built in 1855 and closed in 1935. Between November and March, crews digging out the subsoil to make sure it was solid enough to support the road unearthed 66 bodies in pine boxes. The coffins were about six feet long, as you would expect, but much thinner than normal human width because they were compressed by the weight of the soil. There were no grave markers identifying the burials.

Experts from the state archives and the Mississippi State University anthropology department removed and documented the remains. They will study the bones for two years, doing isotope analysis of the teeth to determine what kind of food they ate, and therefore where they lived, as children, before reburying them in a UMMC cemetery used for donated anatomical remains and previous archaeological discoveries.

The number of bodies found at the road site made the excavation and reburial possible while still allowing the road to be built. That is not the case with the most recent discoveries. Soil testing on locations slated to become a parking lot, the American Cancer Society Hope Lodge (an $11 million project) and the Children’s Justice Center have found evidence of 1,000 bodies and probably more than that. Since each reburial costs about $3,000, that would add a whopping $3 million to the budget, money they don’t have. It puts a lot of pressure on the UMMC to find new locations for these construction projects, but they’re doing the right thing and leaving Asylum Hill and its many dead free from development.

The number of bodies found at the road site made the excavation and reburial possible while still allowing the road to be built. That is not the case with the most recent discoveries. Soil testing on locations slated to become a parking lot, the American Cancer Society Hope Lodge (an $11 million project) and the Children’s Justice Center have found evidence of 1,000 bodies and probably more than that. Since each reburial costs about $3,000, that would add a whopping $3 million to the budget, money they don’t have. It puts a lot of pressure on the UMMC to find new locations for these construction projects, but they’re doing the right thing and leaving Asylum Hill and its many dead free from development.

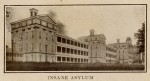

The Mississippi State Insane Asylum was a cutting edge facility when it opened in January 8th, 1855. It was the first state institution for the mentally ill in Mississippi. Before its construction, people deemed insane were kept locked up in the attics and basements of family homes, or chained in jails and prisons. It took almost a decade for the asylum to be built, after appropriation struggles in the legislature and a five-year yellow fever epidemic delayed construction.

The Mississippi State Insane Asylum was a cutting edge facility when it opened in January 8th, 1855. It was the first state institution for the mentally ill in Mississippi. Before its construction, people deemed insane were kept locked up in the attics and basements of family homes, or chained in jails and prisons. It took almost a decade for the asylum to be built, after appropriation struggles in the legislature and a five-year yellow fever epidemic delayed construction.

It was designed by architect Joseph Willis who patterned it after the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum, built in 1848 according to the Kirkbride Plan, an all-encompassing holistic approach to the treatment of mental illness conceived by Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride, a Quaker physician and a lifelong advocate for the curability and humane treatment of the mentally ill. The Mississippi State Insane Asylum was the sixth Kirkbride Plan asylum built in the United States, and the first in the South.

Kirkbride was a co-founder of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane (AMSAII), the organization that in 1921 would become the American Psychiatric Association. He had an enormous influence on how mental illness was treated in second half of the 19th century, thanks largely to his book On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane with Some Remarks on Insanity and Its Treatment, first published in 1854. You can read a digitzed copy of it on the U.S. National Library of Medicine website.

Kirkbride was a co-founder of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane (AMSAII), the organization that in 1921 would become the American Psychiatric Association. He had an enormous influence on how mental illness was treated in second half of the 19th century, thanks largely to his book On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane with Some Remarks on Insanity and Its Treatment, first published in 1854. You can read a digitzed copy of it on the U.S. National Library of Medicine website.

The Kirkbride Plan was an incredibly detailed approach to the construction of mental institutions that would best benefit their patients. He detailed the optimal standards for everything from the staggered design of wings to building materials to the landscaping of the grounds to ventilation and drainage systems. Kirkbride asylums were designed to be large, bright, airy buildings on estates of at least 100 acres to provide inmates with pleasure grounds and land to farm. Kirkbride promoted “moral treatment,” based on the idea that pleasant environs, outdoor work, social interaction, cleanliness and edification of the mind were more effective at curing mental illness than harsh confinement and medical treatments like bleeding and purging.

From On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals:

A hospital for the insane should have a cheerful and comfortable appearance, every thing repulsive and prison-like should be carefully avoided, and even the means of effecting the proper degree of security should be masked, as far as possible, by arrangements of a pleasant and attractive character.

And it can’t be crammed full of beds either. Again from Kirkbride’s book:

All the best authorities agree that the number of insane confined in one hospital, should not exceed two hundred and fifty, and it is very important that at no time should a larger number be admitted than the building is calculated to accommodate comfortably, as a crowded institution cannot fail to exercise an unfavorable influence on the welfare of its patients.

That 250 figure is the maximum number of patients he calculated could be visited daily by the chief medical officer. Anything more than that and the man in charge would have to delegate and that almost inevitably meant a steep decline in conditions. Those 250 residents would be divided into eight classes of mental illness. Each class would get its own ward, and since the sexes were segregated, there were 16 total wards with an average of 15 patients. Each ward should be outfitted with a parlor, a dining room with dumb waiter, a speaking tube leading to the kitchen, a corridor, single rooms for patients, larger rooms for patients who needed their own special attendants, small dormitories with a connected chamber for a group attendant, a clothes room, a bath room, a wash and sink room, a water closet, an infirmary, two works rooms, a museum and reading room, a school room, drying closets, a forced ventilation system along with a natural ventilation system that allowed “fresh cool breezes” to pass through the wards.

When the Mississippi asylum opened, it had a mere 150 inmates, well-within Kirkbride’s maximum. During the Civil War, in 1863 the asylum was taken over by the 46th Indiana Infantry Regiment who used the inmates’ pleasure grounds and vegetable gardens for fortifications, embankments and to supply their troops. Under Reconstruction, African-American patients were first admitted and in 1870 the inmate population doubled to 300. The death rate was contained at around 21 per year, and the state legislature compelled the asylum trustees to visit once a week.

When the Mississippi asylum opened, it had a mere 150 inmates, well-within Kirkbride’s maximum. During the Civil War, in 1863 the asylum was taken over by the 46th Indiana Infantry Regiment who used the inmates’ pleasure grounds and vegetable gardens for fortifications, embankments and to supply their troops. Under Reconstruction, African-American patients were first admitted and in 1870 the inmate population doubled to 300. The death rate was contained at around 21 per year, and the state legislature compelled the asylum trustees to visit once a week.

With the end of Reconstruction in 1877, the legislature stopped giving a crap, funds dried up and the asylum went into a steep decline. When Dr. Thomas J. Mitchell was appointed superintendent in 1878, he found conditions “verging on what the original Bedlam must have been like.” It took a major fire and the death an inmate before the state appropriated funds to install electrical lights and connect the asylum to the city water system (as opposed to the pestilent and drought-prone ponds that were its sole source of water before then) in 1894.

Additions and repairs were made, but not sufficient to keep up with the increase in admissions. By 1920, the Mississippi State Insane Hospital (so renamed in 1900) had 1,670 inmates. By 1930, the number of residents had increased to 2,649. Obviously the Kirkbride Plan was no longer. Finally conditions were so atrocious that in 1935 the hospital was closed and the patients moved to the new state hospital in Whitfield where it remains to this day.

The old asylum was demolished and in 1954, the new University Medical Center was built. Evidence of burials from its asylum days has turned up on occasion, not always handled with the proper respect. In 1990, 20 headstones were reportedly thrown in a gully. A few years after that workers installing a laundry steam line found 44 unmarked graves. Considering how many thousands of poor wretches lived and died in that asylum over the years, the entire campus is a likely cemetery.

The old asylum was demolished and in 1954, the new University Medical Center was built. Evidence of burials from its asylum days has turned up on occasion, not always handled with the proper respect. In 1990, 20 headstones were reportedly thrown in a gully. A few years after that workers installing a laundry steam line found 44 unmarked graves. Considering how many thousands of poor wretches lived and died in that asylum over the years, the entire campus is a likely cemetery.

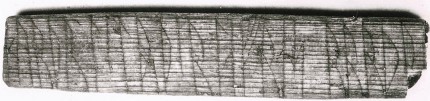

University of California, Davis, paleontologists have found the oldest fossil to capture a vertebrate live birth. The specimen contains the fossil of Chaohusaurus, a Mesozoic marine reptile that is one of the oldest ichthyosaur species, and her three babies in the process of being born. It is 248 million years old, about 10 million years older than any other such fossils. The particular moment captured also strongly suggests that, contra the traditional view, live births in Mesozoic aquatic reptiles first evolved on land rather than in the sea.

University of California, Davis, paleontologists have found the oldest fossil to capture a vertebrate live birth. The specimen contains the fossil of Chaohusaurus, a Mesozoic marine reptile that is one of the oldest ichthyosaur species, and her three babies in the process of being born. It is 248 million years old, about 10 million years older than any other such fossils. The particular moment captured also strongly suggests that, contra the traditional view, live births in Mesozoic aquatic reptiles first evolved on land rather than in the sea.![]() Fortunately, most of the birthing action was captured and the bones are very well preserved. There are three offspring in the fossil frame: one neonate, its body largely underneath the mother’s, one embryo inside the mother’s body cavity and one literally in the middle of being born, with the head outside of the pelvic girdle and the body still inside. Very rarely for an embryonic fossil discovery, the two embryos have clearly articulated skulls, and the one mid-birth even has 23 upper teeth and 16 lower teeth preserved.

Fortunately, most of the birthing action was captured and the bones are very well preserved. There are three offspring in the fossil frame: one neonate, its body largely underneath the mother’s, one embryo inside the mother’s body cavity and one literally in the middle of being born, with the head outside of the pelvic girdle and the body still inside. Very rarely for an embryonic fossil discovery, the two embryos have clearly articulated skulls, and the one mid-birth even has 23 upper teeth and 16 lower teeth preserved. The embryonic skulls are pointing towards the mother’s tail and it’s highly unlikely that all the embryos were in breach position. That means Chaohusaurus were born head first, a feature of live births on land since having the head come out first in water would result in high rates of suffocation. This is why marine mammals today are born tail first.

The embryonic skulls are pointing towards the mother’s tail and it’s highly unlikely that all the embryos were in breach position. That means Chaohusaurus were born head first, a feature of live births on land since having the head come out first in water would result in high rates of suffocation. This is why marine mammals today are born tail first.