Nineteen medieval artifacts from the Sacred Convent of St. Francis in Assisi that have never left Italy since their creation 700 years ago are heading to New York. There are no known extant documents written in Saint Francis’ own hand (historians think he dictated rather than writing himself). These 13th and 14th century manuscripts are the earliest surviving documents about Francis’ and the mendicant order he founded. The exhibition, Friar Francis: Traces, Words and Images, will be on display at the UN Headquarters from November 17th through the 29th but it’s not open to the public. They will be on public display when they move to the Brooklyn Borough Hall from December 2nd to January 14, 2015.

Nineteen medieval artifacts from the Sacred Convent of St. Francis in Assisi that have never left Italy since their creation 700 years ago are heading to New York. There are no known extant documents written in Saint Francis’ own hand (historians think he dictated rather than writing himself). These 13th and 14th century manuscripts are the earliest surviving documents about Francis’ and the mendicant order he founded. The exhibition, Friar Francis: Traces, Words and Images, will be on display at the UN Headquarters from November 17th through the 29th but it’s not open to the public. They will be on public display when they move to the Brooklyn Borough Hall from December 2nd to January 14, 2015.

It’s divided into three sections. The first section, Traces, focuses on documents that are closely connected to Francis’ lifetime. The centerpiece is Codex 338, a collection of the oldest existing copies of Saint Francis’ writings, including the 12 chapters of the Rule of the Friors Minor and the Canticle of the Creatures or Canticle of the Sun, one of Francis’ most celebrated poems. The Canticle of Creatures is the first surviving works written in a dialect (Umbrian) recognizably resembling modern Italian. It is considered the oldest poem in Italian literature. There are also several Papal Bulls issued in the 1220s by popes Honorius III and Gregory IX regarding the regulation of the new order and, after Francis’s canonization in 1228 just two years after his death, ordering the construction of a new church to house his earthly remains.

It’s divided into three sections. The first section, Traces, focuses on documents that are closely connected to Francis’ lifetime. The centerpiece is Codex 338, a collection of the oldest existing copies of Saint Francis’ writings, including the 12 chapters of the Rule of the Friors Minor and the Canticle of the Creatures or Canticle of the Sun, one of Francis’ most celebrated poems. The Canticle of Creatures is the first surviving works written in a dialect (Umbrian) recognizably resembling modern Italian. It is considered the oldest poem in Italian literature. There are also several Papal Bulls issued in the 1220s by popes Honorius III and Gregory IX regarding the regulation of the new order and, after Francis’s canonization in 1228 just two years after his death, ordering the construction of a new church to house his earthly remains.

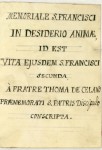

The second section, Words, deals with hagiographies of Francis written after his death. The oldest is a fragmentary parchment of Vita Beati Francisci (The Life of Blessed Francis) by Father Tommaso da Celano commissioned by Pope Gregory IX around the time of Francis’ canonization. There’s also a very rare manuscript of Celano’s second biography, Memoriale Desiderio Animae de Gestis et Verbis Sanctissimi Patris Nostri Francisci (Memorial of the Desire of a Soul Concerning the Deeds and Words of Our Most Holy Father Francis), aka Seconda Vita (Second Life), which was commissioned in the mid-1240s by Crescentius of Jessi, Minister General of the Franciscan Order. A later work from the end of the 14th century, Fioretti di San Francesco (Little Flowers of St. Francis), is an idealized portrayal that would become the most popular hagiography of the saint and the basis for many future works of literature and art about Francis.

The second section, Words, deals with hagiographies of Francis written after his death. The oldest is a fragmentary parchment of Vita Beati Francisci (The Life of Blessed Francis) by Father Tommaso da Celano commissioned by Pope Gregory IX around the time of Francis’ canonization. There’s also a very rare manuscript of Celano’s second biography, Memoriale Desiderio Animae de Gestis et Verbis Sanctissimi Patris Nostri Francisci (Memorial of the Desire of a Soul Concerning the Deeds and Words of Our Most Holy Father Francis), aka Seconda Vita (Second Life), which was commissioned in the mid-1240s by Crescentius of Jessi, Minister General of the Franciscan Order. A later work from the end of the 14th century, Fioretti di San Francesco (Little Flowers of St. Francis), is an idealized portrayal that would become the most popular hagiography of the saint and the basis for many future works of literature and art about Francis.

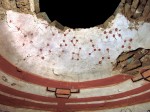

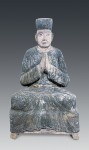

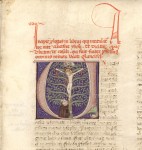

The last section, Images, features depictions of Saint Francis in miniature from illuminated manuscripts. There’s Francis at the foot of the crucified Christ in Ubertino da Casale’s Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Jesu, Francis in a little box amidst floral borders in the Breviarium Fratrum Minorum illuminated by painter Sano di Pietro for the convent of Saint Claire in Siena, and Francis ranking with Adam and Christ on the first page of Genesis in a Bible.

The last section, Images, features depictions of Saint Francis in miniature from illuminated manuscripts. There’s Francis at the foot of the crucified Christ in Ubertino da Casale’s Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Jesu, Francis in a little box amidst floral borders in the Breviarium Fratrum Minorum illuminated by painter Sano di Pietro for the convent of Saint Claire in Siena, and Francis ranking with Adam and Christ on the first page of Genesis in a Bible.

Before these precious and fragile documents could travel, they were subject to months of careful conservation.

Over the past five months, Father Massetti, two other monks and three young restoration experts have cleaned all the manuscripts with a soft paint brush, page by page.

In some, the medieval ink had perforated the page; in others it had faded. Some were missing entire figures or miniatures, others the binding cover.

The restoration experts have repaired the fissures of the parchment with Japanese vegetable fiber or a bovine membrane. They have consolidated the ink and the colorful paintings through a starch gel.

Five of the manuscripts, ranging from the size of a choral book to the pocket format, were unbound, parchment by parchment, and were finally reassembled and stitched back together with a linen thread.

So not only is it the first (and probably only) chance people in the US will have the chance to see these rare artifacts, they will be in the greatest condition they’ve been in for centuries. The exhibition was on display at the Chamber of Deputies, Italy’s lower house of parliament, in the Montecitorio Palace earlier this year, and although many countries have asked to host it, only New York has received the honor. It’s a fitting choice, seeing as 40% of the six million visitors to the Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi hail from the United States.

So not only is it the first (and probably only) chance people in the US will have the chance to see these rare artifacts, they will be in the greatest condition they’ve been in for centuries. The exhibition was on display at the Chamber of Deputies, Italy’s lower house of parliament, in the Montecitorio Palace earlier this year, and although many countries have asked to host it, only New York has received the honor. It’s a fitting choice, seeing as 40% of the six million visitors to the Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi hail from the United States.