The earliest known piece of polyphonic music — choral music written for more than one part — has been discovered in a manuscript at the British Library. It was found by Cambridge doctoral student Giovanni Varelli who was looking through the British Library’s manuscript collections for medieval musical notations. On the last page of Harley 3019, a four-part composite manuscript written in northwest Germany in the early 10th century, Varelli found an inscription that he recognized as Paleofrankish notation, a style that predates the invention of the stave and of which few manuscripts have survived.

The earliest known piece of polyphonic music — choral music written for more than one part — has been discovered in a manuscript at the British Library. It was found by Cambridge doctoral student Giovanni Varelli who was looking through the British Library’s manuscript collections for medieval musical notations. On the last page of Harley 3019, a four-part composite manuscript written in northwest Germany in the early 10th century, Varelli found an inscription that he recognized as Paleofrankish notation, a style that predates the invention of the stave and of which few manuscripts have survived.

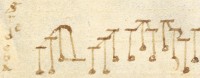

Written on the blank space underneath the conclusion of the hagiography of the late 4th century Saint Maternianus, 6th Bishop of Reims, the inscription consists of two short antiphons (responsory chants): one antiphon honoring St. Boniface martyr and one Rex caelestium terrestrium, praising God as king of heaven and earth. Above the four lines of the antiphons are a series of symbols, vertical lines topped with horizontal dashes with circles on the bottom. An expert in early music notation, Varelli realized that the symbols represented the two melodies of the first chant. The dashes are the main melody of the chant; the circles are a second lower melody to accompany the first. Their placement along the vertical lines indicates the pitch.

A chant with a second melody either above or below it in pitch is known as an organum, an early form of polyphonic music. Although two- and three-part polyphony is discussed in theoretical treatises on musical theory in the 9th and 10th century, this manuscript is the earliest known instance of polyphony as part of a performance tradition rather than something explored in theory. Before this discovery, the earliest known organa were collected in a manuscript called the Winchester Troper, written around the year 1000.

A chant with a second melody either above or below it in pitch is known as an organum, an early form of polyphonic music. Although two- and three-part polyphony is discussed in theoretical treatises on musical theory in the 9th and 10th century, this manuscript is the earliest known instance of polyphony as part of a performance tradition rather than something explored in theory. Before this discovery, the earliest known organa were collected in a manuscript called the Winchester Troper, written around the year 1000.

As well as its age, the piece is also significant because it deviates from the convention laid out in treatises at the time. This suggests that even at this embryonic stage, composers were experimenting with form and breaking the rules of polyphony almost at the same time as they were being written.

“What’s interesting here is that we are looking at the birth of polyphonic music and we are not seeing what we expected,” Varelli said.

“Typically, polyphonic music is seen as having developed from a set of fixed rules and almost mechanical practice. This changes how we understand that development precisely because whoever wrote it was breaking those rules. It shows that music at this time was in a state of flux and development, the conventions were less rules to be followed, than a starting point from which one might explore new compositional paths.”

The manuscript is part of the Harley Collection, the library of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer, and his son, Edward Harley. 2nd Earl of Oxford and Mortimer, which was rapidly assembled from firesales abroad and in London in the first half of the 18th century. Edward’s widow and daughter sold the entire library — more than 7,000 manuscripts, 14,000 charters and 500 rolls — to the nation for £10,000, a steal even then. The acquistion required an act of Parliament, namely the British Museum Act of 1753, the same act that paid Sir Hans Sloane’s heirs £20,000 for his collection of 71,000 objects consisting of books, manuscripts and natural history specimens, antiquities, coins, prints, drawings and ethnographic material to make them the kernel of the country’s first public museum.

Harley 3019 made no particular impression on the curators of the newly minted British Museum. The weird writing at the end of the manuscipt was so insignificant to them, in fact, that they slapped the “Museum Britannicum” stamp right on top of it. (The British Library didn’t split off from the British Museum until 1973.)

Harley 3019 made no particular impression on the curators of the newly minted British Museum. The weird writing at the end of the manuscipt was so insignificant to them, in fact, that they slapped the “Museum Britannicum” stamp right on top of it. (The British Library didn’t split off from the British Museum until 1973.)

Varelli has transcribed the 10th century piece into modern notation and here are Quintin Beer and John Clapham, music undergraduates from his college — St. John’s — performing the Sancte Bonifati martyr.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/F5vqAU_EqG4&w=430]

You can read more about the organum, the notation and the early history of polyphony in Giovanni Varelli’s fascinating paper on the find. To say I know nothing about music theory is a vast understatement, but I was actually able to follow it, much to my amazement. If you’re at all musically inclined, or even just interested in medieval scholarship, it’s very much worth a read.