In 1869 the passage of the Prisoners Property Act had made it legal for the police to use the property of prisoners for instructional purposes, so when the Central Prisoners Property Store was created at London’s Metropolitan Police headquarters in April of 1874, one Inspector Neame began to put together a small collection of objects to train recruits on the detection of burglary using the tools of the burglar’s trade. From that kernel the collection grew over the course of a year into a permanent museum of evidence from a range of crimes housed in the Met’s headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place whose back entrance, No. 1 Great Scotland Yard, became a metonym for the force itself.

In 1869 the passage of the Prisoners Property Act had made it legal for the police to use the property of prisoners for instructional purposes, so when the Central Prisoners Property Store was created at London’s Metropolitan Police headquarters in April of 1874, one Inspector Neame began to put together a small collection of objects to train recruits on the detection of burglary using the tools of the burglar’s trade. From that kernel the collection grew over the course of a year into a permanent museum of evidence from a range of crimes housed in the Met’s headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place whose back entrance, No. 1 Great Scotland Yard, became a metonym for the force itself.

For the first two years of its existence there are no records of the museum having any special visitors. It performed an educational function training police and Inspector Neame made certain it stuck to its purview. When a reporter from The Observer newspaper asked to be granted access to the museum, Neame refused spurring the reporter to print an article dubbing it “the Black Museum.” The first officially recorded visitors were police bigwigs in October of 1877. After that, the museum’s visitors book records a parade of celebrities including Gilbert and Sullivan, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Harry Houdini, the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII), Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, all keen to take a gander at the first museum dedicated to the tools of crime and its perpetrators.

As Scotland Yard (figurative) moved from Scotland Yard (literal), first to the other end of Whitehall Place in 1890 and then to Victoria Street in 1967, the museum moved with it. The current iteration dates to 1981 and is on the first floor of New Scotland Yard on Victoria Street. It has two rooms. The first is a replica of the original 1875 museum in Whitehall and contains weapons used to kill or cause serious injury in London (walking swords were very popular), objects from some of the Yard’s most notorious 19th century cases — Jack the Ripper’s “From Hell” and “Dear Boss” letters, Charles Peace’s burglary kit/violin case — full-head death masks of convicts hanged at Newgate Prison that were used in the Victorian era for phrenological study of their criminal skull bumps, hangman’s nooses labelled with the name of the person who swung from them until dead.

As Scotland Yard (figurative) moved from Scotland Yard (literal), first to the other end of Whitehall Place in 1890 and then to Victoria Street in 1967, the museum moved with it. The current iteration dates to 1981 and is on the first floor of New Scotland Yard on Victoria Street. It has two rooms. The first is a replica of the original 1875 museum in Whitehall and contains weapons used to kill or cause serious injury in London (walking swords were very popular), objects from some of the Yard’s most notorious 19th century cases — Jack the Ripper’s “From Hell” and “Dear Boss” letters, Charles Peace’s burglary kit/violin case — full-head death masks of convicts hanged at Newgate Prison that were used in the Victorian era for phrenological study of their criminal skull bumps, hangman’s nooses labelled with the name of the person who swung from them until dead.

The second room covers 20th century crimes and has display cabinets dedicated to Famous Murders, Notorious Poisoners, Murder of Police Officers, Royalty, Bank Robberies, Espionage, Sieges, Hostages and Hijacking. Dennis Nilsen, serial killer of at least 12 boys and young men, is eerily represented by the small white stove and stock pot he used to boil the flesh off the bones of his victims before disposing of them. There’s the oil drum John George Haigh used to dissolve his six victims in concentrated sulfuric acid and the gallstone that survived the acid bath to help identify the victim. The museum has the ricin pellet used to assassinate Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov and a replica of the umbrella used to fire the pellet into him as he waited at a bus stop on Waterloo Bridge on September 7th, 1978.

The second room covers 20th century crimes and has display cabinets dedicated to Famous Murders, Notorious Poisoners, Murder of Police Officers, Royalty, Bank Robberies, Espionage, Sieges, Hostages and Hijacking. Dennis Nilsen, serial killer of at least 12 boys and young men, is eerily represented by the small white stove and stock pot he used to boil the flesh off the bones of his victims before disposing of them. There’s the oil drum John George Haigh used to dissolve his six victims in concentrated sulfuric acid and the gallstone that survived the acid bath to help identify the victim. The museum has the ricin pellet used to assassinate Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov and a replica of the umbrella used to fire the pellet into him as he waited at a bus stop on Waterloo Bridge on September 7th, 1978.

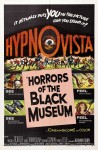

The museum’s macabre displays and exclusivity have inspired documentaries, a radio show hosted by Orson Welles and the 1959 horror classic Horrors of the Black Museum (in HypnoVista!) whose producer and writer, Herman Cohen, finagled a pass to visit the Black Museum via an inspector friend. It’s still part of the Met’s Crime Academy, mainly used today as a lecture theater, and you still have to make an appointment to see its collection of 20,000 objects. Appointments are very hard to come by; even serving police officers have to book a date.

The museum’s macabre displays and exclusivity have inspired documentaries, a radio show hosted by Orson Welles and the 1959 horror classic Horrors of the Black Museum (in HypnoVista!) whose producer and writer, Herman Cohen, finagled a pass to visit the Black Museum via an inspector friend. It’s still part of the Met’s Crime Academy, mainly used today as a lecture theater, and you still have to make an appointment to see its collection of 20,000 objects. Appointments are very hard to come by; even serving police officers have to book a date.

Every once in a while there has been talk of the museum opening to the public to raise money for the police in this age of budget cuts, but nothing’s ever come of it. Now it seems something might. The Mayor’s Office and the Metropolitan Police are negotiating with the Museum of London to put some of the Black Museum’s artifacts on public display.

Every once in a while there has been talk of the museum opening to the public to raise money for the police in this age of budget cuts, but nothing’s ever come of it. Now it seems something might. The Mayor’s Office and the Metropolitan Police are negotiating with the Museum of London to put some of the Black Museum’s artifacts on public display.

Stephen Greenhalgh, deputy mayor for policing and crime, confirmed the meetings with the museum “about how the fantastic story of the Met Police can be told in their museum,” adding the talks were ongoing and they were looking for sponsorship.

Despite anticipated interest, few exhibitions make money and no decision has yet been made whether visitors will be charged to see the planned exhibition. Curators are currently visiting the historical sites to identify the items they want to display. Officials will then discuss the ethical considerations of putting them on show.

The ethnical considerations primarily being the impact on the families of the victims (or of the criminals, for that matter). I wager they’ll stick to the historical crimes, the developement of modern policing, etc., things that are distant enough not to be horrific reminders to anyone connected with the many tragedies on display.

While the parties sort out the details, you can virtually experience a visit to the Black Museum of yore, courtesy of Hargrave L. Adam’s 1914 book Police Work from Within. (Scroll back to chapter two if you want to enjoy Adam’s extra-special thoughts on how the “education” and “emancipation” of women, scare quotes original, inevitably lead to criminality and death. Sneak preview: the ladies ruined America.)

Also, the full 1954 The Black Museum radio series is available at the Internet Archive. It’s rather fabulous, replete with classic radio dramatic music and re-enactments of the crimes. Each episode covers one particular artifact and tells its story. I’m embedding the playlist below because I can.