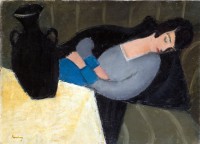

Art historian Gergely Barki was watching Stuart Little with his daughter Lola on Christmas Day 2008 when he recognized a painting above the living room fireplace as Sleeping Lady with a Black Vase, a lost masterpiece by Hungarian Avant-Garde painter Róbert Berény. Berény painted Sleeping Lady with a Black Vase at the turn of 1927/1928. The model was his second wife, cellist Eta Breuer who posed for several of her husband’s post-Impressionist works, often with her cello even though she had stopped playing professionally when she married Berény. Barki, a researcher at the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, is writing a biography of the artist and recognized the painting from the last known record of it: a black and white photograph taken at an exhibition in Hungary in 1928. It was bought at that exhibition by an unknown person, perhaps someone Jewish who fled the country before or during World War II. In the chaos of war and its aftermath, Sleeping Lady with a Black Vase disappeared.

Art historian Gergely Barki was watching Stuart Little with his daughter Lola on Christmas Day 2008 when he recognized a painting above the living room fireplace as Sleeping Lady with a Black Vase, a lost masterpiece by Hungarian Avant-Garde painter Róbert Berény. Berény painted Sleeping Lady with a Black Vase at the turn of 1927/1928. The model was his second wife, cellist Eta Breuer who posed for several of her husband’s post-Impressionist works, often with her cello even though she had stopped playing professionally when she married Berény. Barki, a researcher at the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, is writing a biography of the artist and recognized the painting from the last known record of it: a black and white photograph taken at an exhibition in Hungary in 1928. It was bought at that exhibition by an unknown person, perhaps someone Jewish who fled the country before or during World War II. In the chaos of war and its aftermath, Sleeping Lady with a Black Vase disappeared.

After he beheld the work in living color casually hanging behind Hugh Laurie, Geena Davis and a stylishly attired CGI mouse 90 years after its disappearance, Barki barraged Sony Pictures, Columbia Pictures, cameramen, propmasters, directors, anyone connected with the movie that might have some information about the painting, with emails, but nobody knew where the piece was. It was no longer on Sony’s books because at some point between 1999 and 2002 it had been loaned to the CBS drama Family Law and was removed from the warehouse inventory at that time.

After he beheld the work in living color casually hanging behind Hugh Laurie, Geena Davis and a stylishly attired CGI mouse 90 years after its disappearance, Barki barraged Sony Pictures, Columbia Pictures, cameramen, propmasters, directors, anyone connected with the movie that might have some information about the painting, with emails, but nobody knew where the piece was. It was no longer on Sony’s books because at some point between 1999 and 2002 it had been loaned to the CBS drama Family Law and was removed from the warehouse inventory at that time.

Two years later, he heard from Lisa S., an assistant set designer on Stuart Little. She had bought the painting for $500 from an antiques store in Pasadena specifically for the movie because she thought its cool elegance was perfectly suited for the Little’s New York City apartment. Lisa S. had tracked it down in another warehouse and purchased it from Sony just because she liked it so much. When she contacted Barki, she had no idea of the history of the painting hanging on her bedroom wall.

After Barki visited the painting in person and confirmed its identity, Lisa sold it to a private collector. That collector has now been persuaded to sell it in Hungary. It will go up for auction at the Virag Judit Art Gallery in Budapest on December 13th with a starting price of 110,000 euros ($160,000). Gergely Barki won’t make a dime off of his discovery, but he will have a great story to tell in his biography of the artist.

After Barki visited the painting in person and confirmed its identity, Lisa sold it to a private collector. That collector has now been persuaded to sell it in Hungary. It will go up for auction at the Virag Judit Art Gallery in Budapest on December 13th with a starting price of 110,000 euros ($160,000). Gergely Barki won’t make a dime off of his discovery, but he will have a great story to tell in his biography of the artist.

Róbert Berény’s fame today is centered around his being one of The Eight, a group of artists who introduced the Post-Impressionist avant-garde to Hungary in 1909. He had studied art in Paris starting when he was 17 years old in 1904, exhibiting with the French Fauvists and then incorporating the influence of Cezanne and Matisse into his work with The Eight. The Eight had a profound influence on Hungarian culture, literature and music as well as the visual arts.

In addition to his work in painting and other graphic arts (he designed a well known propaganda poster entitled To Arms! To Arms! for Béla Kun’s Hungarian Revolution of 1919), Berény was also a writer, violinist, pianist, composer and inventor who experimented with moving film and even made an early version of 3D glasses. He and his first wife Ilona Somló, nicknamed Léni, were also close friends with pioneering psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi and were involved in early psychoanalysis experiments including ones on telepathy.

In addition to his work in painting and other graphic arts (he designed a well known propaganda poster entitled To Arms! To Arms! for Béla Kun’s Hungarian Revolution of 1919), Berény was also a writer, violinist, pianist, composer and inventor who experimented with moving film and even made an early version of 3D glasses. He and his first wife Ilona Somló, nicknamed Léni, were also close friends with pioneering psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi and were involved in early psychoanalysis experiments including ones on telepathy.

In his personal life, Berény was a notorious lothario. Among his lovers are numbered Marlene Dietrich and a so-called “Russian princess” who may actually have been Anna Anderson, the Polish factor worker who for decades claimed to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia, youngest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra and magical survivor of the firing squad that slaughtered the Romanovs in 1918.