On Wednesday, December 17th, Mexico City celebrated the 224th anniversary of the rediscovery of the Aztec Sun Stone, the basalt monolith carved under the reign of Moctezuma II just a few years before the Spanish conquest. The circular stone, 12 feet in diameter and weighing more than 24 tons, was originally painted in brilliant red, blue, yellow and white. Archaeologists believe it was placed on top of the main platform of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City), perhaps initially intended to be a sacrificial altar but then erected vertically when the massive stone cracked so it was no longer the thick drum-shape of traditional altars.

On Wednesday, December 17th, Mexico City celebrated the 224th anniversary of the rediscovery of the Aztec Sun Stone, the basalt monolith carved under the reign of Moctezuma II just a few years before the Spanish conquest. The circular stone, 12 feet in diameter and weighing more than 24 tons, was originally painted in brilliant red, blue, yellow and white. Archaeologists believe it was placed on top of the main platform of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City), perhaps initially intended to be a sacrificial altar but then erected vertically when the massive stone cracked so it was no longer the thick drum-shape of traditional altars.

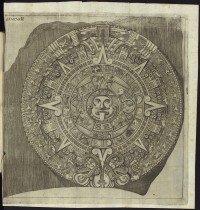

It is a world-famous icon of Aztec sculpture, but there are competing theories on what the imagery carved onto the stone represents. According to the National Museum of Anthropology, at the center of the monolith is the face of the solar deity Tonatiuh inside the glyph “ollin” meaning “movement.” He holds a human heart in each hand and his tongue is the stone knife used for sacrifices. Four squares around his face contain the glyphs for the four previous cycles of creation and destruction. Concentric rings surrounding the central figure contain multiple calendar glyphs: the first ring has the glyphs for 20 of the 260 days in the Aztec calendar, the second features small boxes that may represent the 52 years of an Aztec century. You can examine the carving in glorious high resolution on Google Art Project.

After the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521, Hernán Cortés ordered all Aztec religious icons removed and replaced them with Christian ones. The Sun Stone was toppled and dumped carved side up on the Zócalo, the main square of Mexico City. A few decades later, Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar, the second Archbishop of Mexico, ordered the stone, which he considered an evil, satanic influence on the city’s residents, flipped carved side down and buried. There it remained entirely forgotten until December 17th, 1790, when it was unearthed less than two feet under the surface by workers repaving the square. They propped it upright next to the find spot.

After the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521, Hernán Cortés ordered all Aztec religious icons removed and replaced them with Christian ones. The Sun Stone was toppled and dumped carved side up on the Zócalo, the main square of Mexico City. A few decades later, Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar, the second Archbishop of Mexico, ordered the stone, which he considered an evil, satanic influence on the city’s residents, flipped carved side down and buried. There it remained entirely forgotten until December 17th, 1790, when it was unearthed less than two feet under the surface by workers repaving the square. They propped it upright next to the find spot.

Mexican astronomer, anthropologist, historian and writer Antonio de León y Gama documented the find. He commissioned Francisco de Agüera to make a highly accurate and detailed drawing of the Sun Stone, the first known image of it ever made. In 1792, León y Gama published Descripción histórica y cronológica de las dos piedras que con ocasión del nuevo empedrado que se esta formando en la plaza principal de México, se hallaron en ella el año de 1790 [Historical and Chronological Description of the Two Stones that were Discovered in 1790 in the Main Square of Mexico City] about the discovery of the stone and the statue of the Aztec earth goddess Coatlicue. It was León y Gama who, recognizing the calendar glyphs, interpreted the monolith as a timekeeping device, a giant sundial to mark astronomical events like solstices. His view dominated the scholarship for close to a hundred years. Even today the piece is commonly called the Aztec Calendar Stone.

It was Antonio de León y Gama who rescued the stone from further disrespect. The Viceroy of New Spain and the Church wanted to use the stone as a step leading up to the entrance of the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary, the church built in the shadow of the Templo Mayor ruins 20 years or so after Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar had ordered the Sun Stone buried for its satanism. Letting parishioners stomp their dirty shoes all over a sacred Aztec artifact would have been a satisfying symbol of the triumph of Christianity over paganism. It also would have been a conservation disaster. León y Gama persuaded Viceroy Juan Vicente de Güemes, 2nd Count of Revillagigedo, that since the stone wasn’t really a pagan idol like the statue of Coatlicue, but rather a calendar, it should be properly displayed, not trampled. The stone placed on the exterior wall of the Cathedral’s southwest tower where it became a popular attraction known as “Montezuma’s Clock.”

It was Antonio de León y Gama who rescued the stone from further disrespect. The Viceroy of New Spain and the Church wanted to use the stone as a step leading up to the entrance of the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary, the church built in the shadow of the Templo Mayor ruins 20 years or so after Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar had ordered the Sun Stone buried for its satanism. Letting parishioners stomp their dirty shoes all over a sacred Aztec artifact would have been a satisfying symbol of the triumph of Christianity over paganism. It also would have been a conservation disaster. León y Gama persuaded Viceroy Juan Vicente de Güemes, 2nd Count of Revillagigedo, that since the stone wasn’t really a pagan idol like the statue of Coatlicue, but rather a calendar, it should be properly displayed, not trampled. The stone placed on the exterior wall of the Cathedral’s southwest tower where it became a popular attraction known as “Montezuma’s Clock.”

The Aztec Sun Stone stayed on the Cathedral until 1882 when it was moved along custom-built tracks two blocks to the new National Museum. Three years after that it moved the museum’s Gallery of Monoliths. In 1964, the Sun Stone was moved one last time, to the newly built National Museum of Anthropology. Now the museum can celebrate its own 50 year anniversary, the 50th anniversary of the Sun Stone’s final move and the 224th anniversary of the stone’s rediscovery all at the same time.

The Aztec Sun Stone stayed on the Cathedral until 1882 when it was moved along custom-built tracks two blocks to the new National Museum. Three years after that it moved the museum’s Gallery of Monoliths. In 1964, the Sun Stone was moved one last time, to the newly built National Museum of Anthropology. Now the museum can celebrate its own 50 year anniversary, the 50th anniversary of the Sun Stone’s final move and the 224th anniversary of the stone’s rediscovery all at the same time.