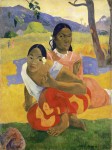

The principles are being cagey about the details, but it seems that a real live Swiss private collection has sold Paul Gaugin’s Nafea Faa Ipoipo? or When Will You Marry? to Qatar for something in the neighborhood of $300 million. The 1892 painting of two young Tahitian women was sold by Rudolf Staechelin, a former Sotheby’s executive in Basel, Switzerland, who runs the family trust of 20 Impressionist and Post-Impressionists paintings collected by his grandfather, also named Rudolf Staechelin. He would neither confirm nor deny that the buyer was Qatar, but that’s what inside sources have claimed, and the oil-rich state has been famously snapping up artworks for record prices over the past years in its quest to develop a world-class museum collection. The previous record price for a painting was set when Qatar bought Paul Cézanne’s The Card Players for $250 million in 2011.

The principles are being cagey about the details, but it seems that a real live Swiss private collection has sold Paul Gaugin’s Nafea Faa Ipoipo? or When Will You Marry? to Qatar for something in the neighborhood of $300 million. The 1892 painting of two young Tahitian women was sold by Rudolf Staechelin, a former Sotheby’s executive in Basel, Switzerland, who runs the family trust of 20 Impressionist and Post-Impressionists paintings collected by his grandfather, also named Rudolf Staechelin. He would neither confirm nor deny that the buyer was Qatar, but that’s what inside sources have claimed, and the oil-rich state has been famously snapping up artworks for record prices over the past years in its quest to develop a world-class museum collection. The previous record price for a painting was set when Qatar bought Paul Cézanne’s The Card Players for $250 million in 2011.

The grandson said that the works had never been hung in his family’s home because they were too precious and that he saw them in a museum along with everyone else. He has decided to sell, he said, because it is the time in his life to diversify his assets. “In a way it’s sad,” he said, “but on the other hand, it’s a fact of life. Private collections are like private persons. They don’t live forever.” […]

“The real question is why only now?” Mr. Staechelin said of the Gauguin sale. “It’s mainly because we got a good offer. The market is very high and who knows what it will be in 10 years. I always tried to keep as much together as I could.” He added, “Over 90 percent of our assets are paintings hanging for free in the museum.”

“For me they are family history and art,” he said of the artworks. “But they are also security and investments.”

The Gaugin painting and the rest of the Staechelin collection has been on long-term loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel since the death of the first Rudolf Staechelin in 1946. The main building of the Kunstmuseum is closing this month for a major refurbishment. A selection of its masterpieces will be shown at other museums in Basel and Spain until it reopens in April of 2016. This temporary closing spurred Staechelin to seek a new loan contract with the canton. Talks did not go smoothly, and although the canton tried to get the collection back for the reopening, Staechelin cancelled the loan by invoking a provision that required the works be on public display at all times.

The Gaugin painting and the rest of the Staechelin collection has been on long-term loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel since the death of the first Rudolf Staechelin in 1946. The main building of the Kunstmuseum is closing this month for a major refurbishment. A selection of its masterpieces will be shown at other museums in Basel and Spain until it reopens in April of 2016. This temporary closing spurred Staechelin to seek a new loan contract with the canton. Talks did not go smoothly, and although the canton tried to get the collection back for the reopening, Staechelin cancelled the loan by invoking a provision that required the works be on public display at all times.

Now Rudolf Staechelin is looking for a new museum in which to house the collection. It has to be a top museum that can afford the security and insurance and that will accept the works on loan without a lending fee. They must also promise to blend the paintings into their permanent collection instead of grouping them together.

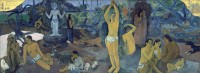

As for the $300 million Nafea Faa Ipoipo?, the buyer won’t take ownership until January of 2016. For now it is still in Basel, on display at a Gauguin exhibition at the Beyeler Foundation from today until June 28th. This special exhibition brings together 50 paintings and sculptures by Gaugin from museums and private collections in 13 countries. It took the museum six years to arrange so broad a show that covers Gaugin’s entire output but focuses on his work in Tahiti and the Marquesas (1891 – 1903). In returned for a loan of Picasso works, they secured a spectacular work from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston: the monumental D’où venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous? (Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?), which at 4’7″ high and 12’3″ wide almost never travels.

As for the $300 million Nafea Faa Ipoipo?, the buyer won’t take ownership until January of 2016. For now it is still in Basel, on display at a Gauguin exhibition at the Beyeler Foundation from today until June 28th. This special exhibition brings together 50 paintings and sculptures by Gaugin from museums and private collections in 13 countries. It took the museum six years to arrange so broad a show that covers Gaugin’s entire output but focuses on his work in Tahiti and the Marquesas (1891 – 1903). In returned for a loan of Picasso works, they secured a spectacular work from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston: the monumental D’où venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous? (Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?), which at 4’7″ high and 12’3″ wide almost never travels.

Another star of the show is a 1902 sculpture called Thérèse which disappeared from public view in 1980. It turns out to have been unpublished in a private collection in London. The director of the Beyeler Foundation saw it at the Lefevre Fine Art in London last October and arranged a loan of the figure for the exhibition. Thérèse is a notorious figure from Gaugin’s life. Depicting a Polynesian woman who worked for the Catholic Bishop of the Marquesas Islands Joseph Martin, Thérèse was displayed in front of the artist’s home along with a companion piece: Père Paillard, or Father Lechery. It was no mystery who those sculptures were meant to represent.

Another star of the show is a 1902 sculpture called Thérèse which disappeared from public view in 1980. It turns out to have been unpublished in a private collection in London. The director of the Beyeler Foundation saw it at the Lefevre Fine Art in London last October and arranged a loan of the figure for the exhibition. Thérèse is a notorious figure from Gaugin’s life. Depicting a Polynesian woman who worked for the Catholic Bishop of the Marquesas Islands Joseph Martin, Thérèse was displayed in front of the artist’s home along with a companion piece: Père Paillard, or Father Lechery. It was no mystery who those sculptures were meant to represent. Père Paillard is written clearly across its base and Monseigneur Martin had a servant named Thérèse who was one of several reputed to have been the recipient of the bishop’s sexual advances. Since the bishop repeatedly admonished Gaugin for his sexual relationships with local women, the artist expressed his opinion of the priest’s moral consistency with this pair of sculptures. Père Paillard is on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and will not be part of the Beyeler exhibition with its newly rediscovered mate, alas.

Père Paillard is written clearly across its base and Monseigneur Martin had a servant named Thérèse who was one of several reputed to have been the recipient of the bishop’s sexual advances. Since the bishop repeatedly admonished Gaugin for his sexual relationships with local women, the artist expressed his opinion of the priest’s moral consistency with this pair of sculptures. Père Paillard is on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and will not be part of the Beyeler exhibition with its newly rediscovered mate, alas.