More than 35,000 people lined the cortege route on Sunday, and more than 20,000 visitors have queued up to pay their respects to the mortal remains of Richard III in the three days the coffin has been on view at Leicester Cathedral. The culmination of this week of events is today’s reburial service.

More than 35,000 people lined the cortege route on Sunday, and more than 20,000 visitors have queued up to pay their respects to the mortal remains of Richard III in the three days the coffin has been on view at Leicester Cathedral. The culmination of this week of events is today’s reburial service.

A few tidbits about the service:

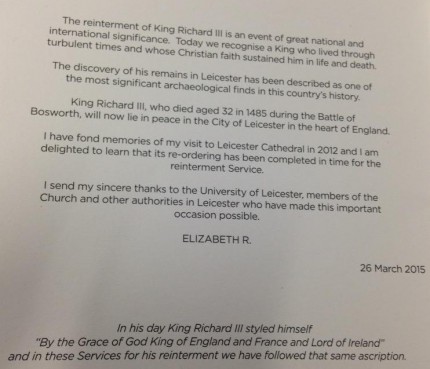

- The current royal family will be represented by the Countess of Wessex, wife of Prince Edward, and the Duke of Gloucester who shares a title Richard held before he was king, but Queen Elizabeth II has written a tribute to Richard that will be printed in the service program.

- After the service the coffin will be lowered into a tomb built of Yorkshire Swaledale stone. This is the first time the public will witness the actual lowering of a monarch’s coffin into the grave.

- Descendents of people who fought at the Battle of Bosworth will be present.

- Benedict Cumberbatch, who is playing Richard III in an upcoming BBC series based on Shakespeare’s relevant histories, will read a poem called Richard written for the occasion by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy. Also University of Leicester historian Kevin Schürer found Benedict Cumberbatch and Richard III are second cousins 16 times removed, see abridged genealogy here (pdf).

- After the service the Cathedral will be closed to the public until Friday when the new memorial will be in place.

If you missed the transfer of the remains from the University of Leicester to the Cathedral and the Compline service that followed, Channel 4 has their entire coverage of the event available on their website. They will again be the only television channel broadcasting the reinterment live, but it looks like a sure bet that they’ll have that video available on their website if you miss it live.

If you missed the transfer of the remains from the University of Leicester to the Cathedral and the Compline service that followed, Channel 4 has their entire coverage of the event available on their website. They will again be the only television channel broadcasting the reinterment live, but it looks like a sure bet that they’ll have that video available on their website if you miss it live.

Channel 4’s live coverage begins at 10:00 AM GMT (6:00 AM EST). In addition to airing the service itself, it will include discussions with some of the guests and the people involved in the discovery and reburial. The program will last three hours until 1:00 PM GMT. They’ll air a one-hour highlight reel at 8:00 PM GMT.

Needless to say, I’ll be watching live.

6:00 AM EDIT: Or rather I would be, if the Channel 4 viewer weren’t giving me an error. :angry:

7:06 AM: I can’t get it to work, dammit. I’ll have to watch it on demand later. For now, I’m listening to BBC Radio Leicester’s live coverage and following the Twitter RichardReburied hashtag.

The Leicester Mercury is liveblogging the reburial, as is the city’s dedicated King Richard in Leicester website.

7:23 AM: Here’s Queen Elizabeth II’s message:

7:31 AM: Professor Gordon Campbell, the University of Leicester’s public orator (dude, they have a public orator!) opened with a euology that was a brief, dry summary of Richard’s life, the discovery of his remains and the significance of his mitochondrial DNA. They don’t orate like they used to, man.

7:37 AM: The Dean just placed Richard’s personal Book of Hours, found in his tent after the Battle of Bosworth, on a cushion in front of the coffin.

7:49 AM: Check out this amazing headshake and eyeroll from John Ashdown-Hill of the Richard III Society. That’s Philippa Langley sitting next to him. I’m guessing is has something to do with insufficent recognition of Langley and the Society’s work in making this day come to pass.

7:58 AM: What a poetic sermon from the Bishop of Leicester.

8:02 AM: Here’s a neat story about the artist who made the ceramic vessels to hold the soils of Fotheringhay, Middleham and Fenn Lane that were blessed on Sunday and will be interred with Richard’s remains today. Michael Ibsen made the box, and a handsome one it is.

8:07 AM: Classic ashes to ashes dust to dust reading over the coffin which is now being lowered into the tomb.

8:08 AM: Apparently the soils will be sprinkled over the coffin, not placed in the tomb in the handsome box.

8:14 AM: “Grant me the carving of my name…” Dame Carol Ann Duffy’s poem is beautiful and moving and Benedict Cumberbatch recited it like, well, a pro.

Richard

My bones, scripted in light, upon cold soil,

a human braille. My skull, scarred by a crown,

emptied of history. Describe my soul

as incense, votive, vanishing; your own

the same. Grant me the carving of my name.

These relics, bless. Imagine you re-tie

a broken string and on it thread a cross,

the symbol severed from me when I died.

The end of time – an unknown, unfelt loss –

unless the Resurrection of the Dead…

or I once dreamed of this, your future breath

in prayer for me, lost long, forever found;

or sensed you from the backstage of my death,

as kings glimpse shadows on a battleground.

8:27 AM: And that’s all, folks. The luminaries are processing out. It was less than an hour long. No long, boring speeches. Beautiful music. Great poem. Epic Ricardian eyeroll. I couldn’t ask for more.

8:35 AM: Channel 4’s coverage continues with interviews of some of the principals — Langley, Ibsen, etc. I wonder if they’ll ask Philippa about the epic eyeroll. If, like me, you’re having trouble viewing the broadcast on Channel 4’s website, you can watch it online here instead. Wish I had remembered that an hour ago. :blankstare:

8:41 AM: They did ask John Ashdown-Hill about his eyeroll and he minced no words. He hoped the service would be peaceful, but “we still seem to be dealing with some lies from Leicester.” Daaaaamn… He wouldn’t specify the lies beyond saying they got Richard’s birthday wrong on the program.

8:45 AM: Benedict Cumberbatch was blown away by the poem. He looks stylish wearing a white rose lapel pin.