Researchers have found the earliest known evidence of dentistry in the molar of a Palaeolithic man who lived between 13,820 and 14,160 years ago. The young man, who was around 25 years old at the time of death, had a cavity removed with a sharp flint, beating the dental work previously thought to be the oldest (a molar found in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that was perforated by a bow drill) by 5,000 years.

Researchers have found the earliest known evidence of dentistry in the molar of a Palaeolithic man who lived between 13,820 and 14,160 years ago. The young man, who was around 25 years old at the time of death, had a cavity removed with a sharp flint, beating the dental work previously thought to be the oldest (a molar found in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that was perforated by a bow drill) by 5,000 years.

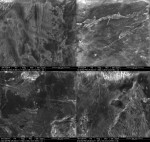

The skeleton was found in the Ripari Villabruna rock shelter in the Dolomite mountains of northern Italy in 1988. The skeletal remains had been laid to rest in a shallow grave along with what were probably the hunter’s most prized possessions: a flint knife, a hammer stone, a flint blade and a piece of sharpened bone. Stones decorated with red ochre marked the burial mound. The bones were in usually good condition and a large cavity in his lower right third molar was noticed at the time, but the attempted treatment was not visible to the naked eye. It was only when researchers recently examined the molar with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) that they realized the cavity was signficantly larger than the decayed tissue and that there were striations and chips on the walls of the cavity even in the most inaccessible parts of the tooth.

The skeleton was found in the Ripari Villabruna rock shelter in the Dolomite mountains of northern Italy in 1988. The skeletal remains had been laid to rest in a shallow grave along with what were probably the hunter’s most prized possessions: a flint knife, a hammer stone, a flint blade and a piece of sharpened bone. Stones decorated with red ochre marked the burial mound. The bones were in usually good condition and a large cavity in his lower right third molar was noticed at the time, but the attempted treatment was not visible to the naked eye. It was only when researchers recently examined the molar with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) that they realized the cavity was signficantly larger than the decayed tissue and that there were striations and chips on the walls of the cavity even in the most inaccessible parts of the tooth.

The striations look like tiny versions of cut marks on bone. The research team experimented with sharpened wood, bone and flint points on the enamel of three molars and confirmed that the striations and enamel chipping on the cavity walls were made before death by pointed stone tool scratching and digging into the lesion. That means someone took a very small, very sharp tool, probably a flint, and dug out as much of the decay as they could. The striations go on in all different directions so the cavedentist really got down in there, changing angles and positions to clean out the rotted parts. The pain and difficulty of this procedure suggests that the dangers of tooth decay were known in the Late Upper Palaeolithic.

The striations look like tiny versions of cut marks on bone. The research team experimented with sharpened wood, bone and flint points on the enamel of three molars and confirmed that the striations and enamel chipping on the cavity walls were made before death by pointed stone tool scratching and digging into the lesion. That means someone took a very small, very sharp tool, probably a flint, and dug out as much of the decay as they could. The striations go on in all different directions so the cavedentist really got down in there, changing angles and positions to clean out the rotted parts. The pain and difficulty of this procedure suggests that the dangers of tooth decay were known in the Late Upper Palaeolithic.

Evidence of Palaeolithic concern for dental hygiene has been found before. They were known to use toothpicks made of bone or wood to clean food particles stuck between their teeth, but this is the first evidence of treatment of tooth decay. It’s the first evidence of surgical intervention period.

The find represents the oldest archaeological example of an operative manual intervention on a pathological condition, according to researchers led by Stefano Benazzi, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Bologna.

“It predates any undisputed evidence of dental and cranial surgery, currently represented by dental drillings and cranial trephinations dating back to the Mesolithic-Neolithic period, about 9,000-7,000 years ago,” Benazzi said.

You can read the full study here (pdf).