Title belts in boxing today are the ostentatious displays of official victors, but it wasn’t always thus. In the 19th century, before the rules for title championships were encoded, both the title and the waist accessory were more loosely assigned. John L. Sullivan was considered the first heavyweight champion of the world, even though any consistent standard would give English boxer Jem Mace that honor for his defeat of Tom Allen in 1870. Why not, then, have a belt made to celebrate one fighter’s triumph even when said fight resulted in a draw?

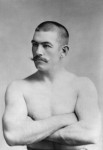

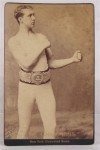

The draw in question was a brutal contest between John L. Sullivan and English fighter Charles Mitchell. Nobody saw it coming. The opponents were evenly matched in some ways. They were close in age (Sullivan was 29, Mitchell 26) and close in height (Sullivan 5’10 1/2″, Mitchell 5’9″). Both had championship titles. Both had winning records, although only Sullivan was undefeated. The big difference was weight. Rarely weighing more than 160 pounds, Charley Mitchell was a welterweight, a middleweight on a good day. John L. Sullivan was a heavyweight who was 190 pounds at his leanest and who regularly crossed the 200-pound mark. (He weighed 238 pounds when he knocked out 170-pound middleweight Jack Burke in 1885.)

The draw in question was a brutal contest between John L. Sullivan and English fighter Charles Mitchell. Nobody saw it coming. The opponents were evenly matched in some ways. They were close in age (Sullivan was 29, Mitchell 26) and close in height (Sullivan 5’10 1/2″, Mitchell 5’9″). Both had championship titles. Both had winning records, although only Sullivan was undefeated. The big difference was weight. Rarely weighing more than 160 pounds, Charley Mitchell was a welterweight, a middleweight on a good day. John L. Sullivan was a heavyweight who was 190 pounds at his leanest and who regularly crossed the 200-pound mark. (He weighed 238 pounds when he knocked out 170-pound middleweight Jack Burke in 1885.)

The weight of his punch was in keeping with his physique. Sullivan had defeated Paddy Ryan in 1882 to claim the title heavyweight champion of America and kept it for a decade until Gentleman Jim Corbett relieved him of it by knock-out in 1892. Ryan would later describe being hit by Sullivan as feeling as if “a telegraph pole had been shoved against me endways.” Sullivan was expected to knock out Mitchell, who pound for pound was one of the hardest hitters in the ring. Pound for pound being the salient issue. Mitchell had a reputation for being fast and avoiding blows — in his memoirs Sullivan called Mitchell a “bombastic sprinter boxer”) — but despite his proven ability to hit and run, Mitchell was considered simply too puny to take out Sullivan.

Mitchell wasn’t intimidated. Not only did he want this fight, he actively picked it for five years. Mitchell and Sullivan first went at each other in a bout at Madison Square Garden in 1883. Police stopped the fight after the third round, three rounds that Sullivan dominated with one glaring exception: Mitchell had knocked him down in the first round with a left hook to the chin. Sullivan had never hit the floor before in his career and he didn’t take kindly to it. Mitchell vociferously demanded a rematch and one was actually proposed for the next day but Sullivan would not accept it. A rematch was scheduled for June 30th, 1884, but it was cancelled when Sullivan turned up drunk.

Mitchell wasn’t intimidated. Not only did he want this fight, he actively picked it for five years. Mitchell and Sullivan first went at each other in a bout at Madison Square Garden in 1883. Police stopped the fight after the third round, three rounds that Sullivan dominated with one glaring exception: Mitchell had knocked him down in the first round with a left hook to the chin. Sullivan had never hit the floor before in his career and he didn’t take kindly to it. Mitchell vociferously demanded a rematch and one was actually proposed for the next day but Sullivan would not accept it. A rematch was scheduled for June 30th, 1884, but it was cancelled when Sullivan turned up drunk.

The beef was not squashed, only refrigerated. When Sullivan traveled to London in November of 1887 to fight in front of the Prince of Wales, Mitchell taunted him, telling the press that Sullivan was afraid to fight him because he’d knocked him down four years earlier. One reporter described Mitchell as “snarling out challenges to [Sullivan] by the dozen.” Sullivan, who fought more than 50 exhibitions during his two months in England as Mitchell goaded him relentlessly, was livid. He agreed to fight Mitchell on March 10th, 1888.

When this fight took place, bare-knuckle prizefighting was illegal in all 38 states and several countries. Bouts had to be arranged in secret locations and even so were often broken up by the police. Fighters and promoters were regularly arrested and fined, sometimes sentenced to prison. Fleeing the state or country in disguise after a fight was commonplace. The thorny search for a location was resolved when Baron Gustave de Rothschild offered to host the fight on the grounds of his Château de Laversine, a stately home on the banks of the River Oise three miles north of Chantilly in the Picardy region of northern France.

When this fight took place, bare-knuckle prizefighting was illegal in all 38 states and several countries. Bouts had to be arranged in secret locations and even so were often broken up by the police. Fighters and promoters were regularly arrested and fined, sometimes sentenced to prison. Fleeing the state or country in disguise after a fight was commonplace. The thorny search for a location was resolved when Baron Gustave de Rothschild offered to host the fight on the grounds of his Château de Laversine, a stately home on the banks of the River Oise three miles north of Chantilly in the Picardy region of northern France.

The 24-foot ring Mitchell had insisted on (as opposed to the 16-foot ring Sullivan wanted to help corral Mitchell’s avoidance tactics) was erected outdoors near the stables. The fight began at 12:50 PM. At first it seemed to be going as expected, with Sullivan pummeling the bejesus out of Mitchell, knocking him down repeatedly in the first eight rounds. Mitchell landed some good ones, though, and as time passed, his running game served him well and he seemed to be getting stronger while Sullivan’s strength faded. It started raining during the sixth round or so, and soon the rain turned torrential, transforming the ground to swampland which sapped Sullivan’s energy all the more. Again from John L.’s memoirs:

Running and dropping was [Mitchell’s] game, and to such an extent did he practise the former that, when the fight was over, a track like a sheep run was to be noticed all around the ring. Once he dropped without a blow and received a caution, and after this he went down a number of times for a mere tap.

After three hours and 11 minutes and 39 rounds, both sides agreed to call it a draw, but the fact that the English fall-taking sprinter boxer held out so effectively against the Irish-American Boston Strong Boy felt a lot more like a stinging defeat to Sullivan and his fans. Reams of newsprint were dedicated to musings on how this could have happened. Back in England, Mitchell was hailed as a conquering hero.

To show their appreciation for his having managed to avoid being beaten unconscious, a group of English supporters presented Charley Mitchell with a championship belt.

[A] truly breathtaking belt crafted from British sterling and velvet for presentation to Sullivan’s plucky challenger. The pertinent details are artfully printed on the center plate:

“Presented to Charles Mitchell to Commemorate His Gallant Fight with John L. Sullivan for the Championship of the World on March 10th 1888 near Paris Resulting in a Draw, 39 Rounds being Fought, in 3 Hours 11 Minutes.”

Framing this center plate are portraits of Mitchell and Sullivan in relief, followed by British and American flags topped by a figural lion and eagle respectively, and then further figural plates completing the design against a backing of royal red velvet. On the final plate on the left side, the interior is engraved with the names of the gentlemen who funded this quite clearly expensive token of esteem. A second such engraved plaque is affixed to interior of center panel, though we suspect it was originally attached to the final plate on right. The velvet is well worn and the silver exhibits some tarnishing and storage wear, but the aesthetics remain spectacular after nearly thirteen decades.

This ornate trophy was a slap in Sullivan’s face. He had already had to deal with belt nonsense the year before when Richard K. Fox, editor of the National Police Gazette and holder of a very long grudge against Sullivan for having snubbed him in a saloon once, declared the undefeated Irish-American heavyweight Jake Kilrain the new world champion and gave him a silver championship belt on behalf of the Gazette. Sullivan’s supporters responded by giving him a championship belt of 14-carat gold engraved “Presented to the Champion of Champions, John L. Sullivan, by the Citizens of the United States.” Sullivan’s name was spelled in diamonds, 397 of them, no less. It was the most expensive belt ever given to a fighter. Mitchell’s was the second most expensive. The latter has now sold at auction for $55,000, which is quite modest, really, considering it cost $10,000 to make.

Kilrain, incidentally, was a witness to the Mitchell-Sullivan fight in Chantilly. He had a great vantage point from Mitchell’s corner, and Mitchell would be in his when Kilrain went up against Sullivan for the world heavyweight title in Richburg, Mississippi, in 1889. This would be the last title match fought with bare knuckles under London Prize Ring Rules and it was one for the ages. Fought in the noon sun of a Mississippi July, the bout lasted two hours, 16 minutes and went 75 rounds. Kilrain had to be carried to his corner by the 17th round. Sullivan vomited in the 44th. Scheduled to run 80 rounds, the bout was finally stopped when Kilrain’s cornerman Mike Donovan, very much against his fighter’s wishes, threw in the towel because he was sure Kilrain, who could barely stand by this point, wouldn’t survive a 76th round.

Kilrain, incidentally, was a witness to the Mitchell-Sullivan fight in Chantilly. He had a great vantage point from Mitchell’s corner, and Mitchell would be in his when Kilrain went up against Sullivan for the world heavyweight title in Richburg, Mississippi, in 1889. This would be the last title match fought with bare knuckles under London Prize Ring Rules and it was one for the ages. Fought in the noon sun of a Mississippi July, the bout lasted two hours, 16 minutes and went 75 rounds. Kilrain had to be carried to his corner by the 17th round. Sullivan vomited in the 44th. Scheduled to run 80 rounds, the bout was finally stopped when Kilrain’s cornerman Mike Donovan, very much against his fighter’s wishes, threw in the towel because he was sure Kilrain, who could barely stand by this point, wouldn’t survive a 76th round.

John L. Sullivan and Charley Mitchell died the same year, 1918. Sullivan preceded his old rival by two months to the day, dying of a heart attack at age 59 on February 2nd. Mitchell died at the age of 56 suffering from locomotor ataxia, a progressive neurological disorder of the spinal column which causes jerky and unbalanced gait. Also known as tabes dorsalis, it is a symptom of late-stage syphilis but is not fatal on its own. It’s the underlying condition that killed him. I wonder if he’d have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s or ALS today. Jake Kilrain outlived them both, dying of complications from diabetes in 1937 at 78 years old.