In late 2001, workers doing construction on the site of a former Soviet Army barracks in a northern suburb of Vilnius discovered a mass grave which fragments of military uniforms identified as the final resting place for more than 3,000 soldiers and support staff of Napoleon’s Great Army who died during the horrific retreat from Russia in the winter of 1812. The grave was excavated in two stages in 2002 and the preliminary results of the study of the skeletons were published in February of 2004 (pdf). Thanks to two new studies on the skeletal remains, we now know more about the geographical origin and diet of some of the men and women who died in Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign.

In late 2001, workers doing construction on the site of a former Soviet Army barracks in a northern suburb of Vilnius discovered a mass grave which fragments of military uniforms identified as the final resting place for more than 3,000 soldiers and support staff of Napoleon’s Great Army who died during the horrific retreat from Russia in the winter of 1812. The grave was excavated in two stages in 2002 and the preliminary results of the study of the skeletons were published in February of 2004 (pdf). Thanks to two new studies on the skeletal remains, we now know more about the geographical origin and diet of some of the men and women who died in Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign.

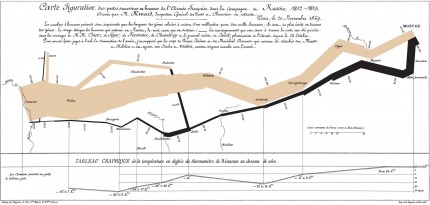

First an infographic. I get emails all the time from people asking me to post their ostensibly history-related infographics and I decline because they tend to be marketing gimmicks that are very light on content. This one is different. Created in 1869 by French civil engineer Charles Joseph Minard, a pioneer of statistics relayed in graphic form, this chart plots the advance of the Great Army into Russia and its devastating retreat. The width of the line marks the size of the army at any given time. The beige line, obese with troops in the beginning, thins out to a quarter of its original size when the army reaches Moscow. The black line then shows the retreating army as it doubles back in the sadly vain attempt to make it out of the Russian winter alive. By the time the black line reaches where the beige line begins, it’s pencil-thin. The 422,000 invasion troops are reduced to 10,000 in retreat, starving, frozen, defeated on an unthinkable scale by a brutal Russian winter and overly extended supply lines.

The deceptively simple chart captures six variables: the size of the army (represented by the thickness of the line), the longitude and latitude of the army (represented by the position of the line), the direction of the army (represented by the two different colored lines), the location of the army on certain dates and, in a line chart underneath the main graphic, the temperature during the retreat. Many cartographers and graphics experts today consider it the greatest information graphic ever made. (Click here for a much larger version translated into English.

The immensity of the disaster that Minard’s graphic conveys so adroitly is exposed on a more human scale by the bones of the fallen. Buttons found in the two trenches of the mass grave identified soldiers and officers from around 30 regiments, most of them infantry, some cavalry, dragoon and foot artillery. There were uniform remains from Italian, Polish and Bavarian regiments as well as the Imperial Guard. There are female skeletons in the mass grave because since 1805 the French army had an official cadre of women working as cooks, laundresses, nurses and sellers of goods like tobacco and alcohol which accompanied the Grand Army in every campaign. Archaeologists were able to determine the sex of 29 female skeletons, but there were probably more women buried with the men as the remains of 1317 individuals were impossible to sex.

The immensity of the disaster that Minard’s graphic conveys so adroitly is exposed on a more human scale by the bones of the fallen. Buttons found in the two trenches of the mass grave identified soldiers and officers from around 30 regiments, most of them infantry, some cavalry, dragoon and foot artillery. There were uniform remains from Italian, Polish and Bavarian regiments as well as the Imperial Guard. There are female skeletons in the mass grave because since 1805 the French army had an official cadre of women working as cooks, laundresses, nurses and sellers of goods like tobacco and alcohol which accompanied the Grand Army in every campaign. Archaeologists were able to determine the sex of 29 female skeletons, but there were probably more women buried with the men as the remains of 1317 individuals were impossible to sex.

The two new studies by University of Central Florida researchers used stable isotope analysis to find out where some of Napoleon’s dead came from and what, if anything, they ate. In one of the studies (pdf), oxygen isotopes in the bones revealed that none of the dead tested were from Vilnius. Of the eight males and one female tested, five of the men were from central and western Europe, three from the Iberian peninsula. The woman was most likely from southern France.

The other study (pdf) took specimens from the bones of 73 men and three women for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis. Carbon isotopes revealed that most of Napoleon’s troops ate wheat in their youth and a few, perhaps from Italy, were raised more on millet. More than a third of the specimens were found to have exceptionally high nitrogen isotope values. While that’s often an indication of a diet high in protein (Richard III, for instance, had a diet rich in game, meat and sea fish and the nitrogen values to prove it), it’s also a reaction to the exact opposite: protein deprivation dramatically raises nitrogen isotope values. Disease can spike nitrogen values as well.

The other study (pdf) took specimens from the bones of 73 men and three women for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis. Carbon isotopes revealed that most of Napoleon’s troops ate wheat in their youth and a few, perhaps from Italy, were raised more on millet. More than a third of the specimens were found to have exceptionally high nitrogen isotope values. While that’s often an indication of a diet high in protein (Richard III, for instance, had a diet rich in game, meat and sea fish and the nitrogen values to prove it), it’s also a reaction to the exact opposite: protein deprivation dramatically raises nitrogen isotope values. Disease can spike nitrogen values as well.

Napoleon’s men were not in good health, even before their ill-fated stop in Vilnius. Research on the teeth of the soldiers in the mass grave showed rampant dental cavities and indications of stress during childhood, and over one-quarter of the dead had likely succumbed to epidemic typhus, a louse-borne disease. A febrile illness like typhus could cause increased loss of body water through urine, sweat, and diarrhea, which may also cause a rise in nitrogen isotopes. And, of course, historical accounts detail how troops fruitlessly scoured the countryside for food and how many of them ate their dead or dying horses.

Consumption of seafood is unlikely to be the cause of the high nitrogen since the frozen Vilnia River wasn’t producing and there were no salted stores to be had. Canning was still in its infancy as French brewer Nicolas Appert had only devised a method to seal food in glass jars in 1809. He did so specifically for the French army, incidentally, after Napoleon offered a 12,000 franc reward to anyone who could solve the military’s thorny supply problems. Glass doesn’t transport well and while a metal can system was invented by Peter Durand in 1810, Durand was British and his patented food preservation products went straight to the Royal Navy, not the Grand Armée.

Consumption of seafood is unlikely to be the cause of the high nitrogen since the frozen Vilnia River wasn’t producing and there were no salted stores to be had. Canning was still in its infancy as French brewer Nicolas Appert had only devised a method to seal food in glass jars in 1809. He did so specifically for the French army, incidentally, after Napoleon offered a 12,000 franc reward to anyone who could solve the military’s thorny supply problems. Glass doesn’t transport well and while a metal can system was invented by Peter Durand in 1810, Durand was British and his patented food preservation products went straight to the Royal Navy, not the Grand Armée.

The culprit is almost certainly prolonged nutritional stress.