Archaeologists and graduate students from the University of Palermo have unearthed what they believe are two 7th century skeletons at the feet of the Temple of Concordia in Agrigento, Sicily. They have yet to be radiocarbon dated, but if the archaeologists are right, the remains are evidence of an Early Christian cemetery in front of the temple in the period shortly after the temple was converted into a church.

Archaeologists and graduate students from the University of Palermo have unearthed what they believe are two 7th century skeletons at the feet of the Temple of Concordia in Agrigento, Sicily. They have yet to be radiocarbon dated, but if the archaeologists are right, the remains are evidence of an Early Christian cemetery in front of the temple in the period shortly after the temple was converted into a church.

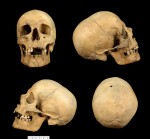

The skeletal remains were found in a single grave. A fully articulated skeleton of what preliminary analysis indicates is an adult male is on top, his skull oriented west and his arms crossed on his chest. Underneath his legs are the bones of the other skeleton; its sex has not yet be determined. No grave goods or artifacts of any kind were found to aid in dating. Excavations are ongoing and the remains will be analyzed to pinpoint their age.

Here’s a video of the excavation shot by tour guide Rosa Maria Montalbano.

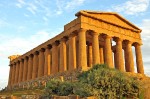

The Temple of Concordia was built around 440 B.C. in Archaic Doric style in the ancient Greek city of Akragas. It’s not certain which deity it was dedicated to, possibly the Dioscuri, the twin brothers Castor and Pollux. The name Concordia was assigned to it by 16th century Dominican friar and historian Tommaso Fazello, known as the Father of Sicilian history or the Sicilian Livy. He got it from a 1st century Roman inscription on a marble slab in the city of Agrigento which read: “CONCORDIAE AGRIGENTINORUM SACRUM RESPUBLICA LILIBITANORUM” or “[Erected] by the republic of the Lilybaeans, as sacred to the concord of the Agrigentines.” (The ancient city of Lilybaeum is modern-day Marsala, where the wine comes from.) Fazello translated that as “Temple of Concordia of the Agrigentines, made by the Republic of the Lilybaeans,” deducing from the inscription that the temple was constructed at the expense of the Lilybaeans after a military defeat.

In fact, the inscription doesn’t say what was erected and in any case it was carved 500 years after the temple was built, so it wouldn’t necessarily be accurate even if it were referring to the temple. Lilybaeum wasn’t founded until the late 300s B.C., so the city didn’t even exist when the temple was built. Historians starting with 18th century classicist Jacques Philippe D’Orville called out the errors in Fazello’s attribution and now it’s universally acknowledged to be false, but the name stuck anyway.

In fact, the inscription doesn’t say what was erected and in any case it was carved 500 years after the temple was built, so it wouldn’t necessarily be accurate even if it were referring to the temple. Lilybaeum wasn’t founded until the late 300s B.C., so the city didn’t even exist when the temple was built. Historians starting with 18th century classicist Jacques Philippe D’Orville called out the errors in Fazello’s attribution and now it’s universally acknowledged to be false, but the name stuck anyway.

The Temple of Concordia was converted into a church in 597 A.D. by archbishop Gregory II of Agrigento (559-630) and there’s a wonderfully juicy story behind it. A biography written by the 7th century monk Leonzio, abbot of Saint Saba in Rome, tells the tale. After Gregory was appointed archbishop entirely against his will (he preferred a life of withdrawn contemplation), a priest and presbytery in Agrigento conspired to replace him as archbishop with a certain Leucio who had been exiled for his heretical beliefs on the incarnation. The conspirators bribed the guards and hid a prostitute named Evodia in Gregory’s chambers while he was at church.

The next morning the conspirators “caught” the prostitute and scandal erupted. They had Gregory arrested and imprisoned. The people of Agrigento loved their archbishop who took care of the poor and performed miraculous healings regularly so they didn’t believe the story. They insisted he be freed and caused enough of a stink that the Pope’s deacon had to smuggle Gregory on a ship to Rome for trial. When he got to Rome, he was jailed for two and a half years before his supporters in Agrigento were able to enlist the aid of the Byzantine Emperor Maurice and the Patriarch to finally secure a trial.

The next morning the conspirators “caught” the prostitute and scandal erupted. They had Gregory arrested and imprisoned. The people of Agrigento loved their archbishop who took care of the poor and performed miraculous healings regularly so they didn’t believe the story. They insisted he be freed and caused enough of a stink that the Pope’s deacon had to smuggle Gregory on a ship to Rome for trial. When he got to Rome, he was jailed for two and a half years before his supporters in Agrigento were able to enlist the aid of the Byzantine Emperor Maurice and the Patriarch to finally secure a trial.

There were more than 100 jurors arrayed against Gregory and only a handful, including the imperial delegation, on his side. It seemed Gregory was doomed, but in a shocking Law & Orderesque twist, Evodia recanted her testimony on the stand, naming the conspirators who had coerced her into setting up the saintly cleric. The conspirators were exiled and Gregory returned to Agrigento, his reputation and position restored. Unwilling to preside over his congregation in a church that had been profaned by the usurper Leucio, Gregory turned his back on the city proper and looked to the Valley of the Temples for his new cathedral.

He chose the Temple of Concordia. Planting the signum, the cross of Christ, over its threshold, Gregory exorcised the ancient pagan demons of Eber and Raps who still dwelled in the temple. (The “demons” may be transmutations of an original double dedication, hence the theory that the temple may have been dedicated to Castor and Pollux.) Now consecrated and holy, the temple was converted into the new cathedral.

Gregory of Agrigento is the patron saint of the conservation of archaeological and architectural patrimony. That’s both ironic and appropriate, because while he destroyed significant parts of the temple to Christianize it, as a church it survived in far better condition than the other temples in Agrigento which were damaged in earthquakes and pillaged for construction material. In the conversion process, all of the temple’s decorative elements and the altar were destroyed. The back wall of the cella (the inner chamber) of the temple was demolished to make a new entrance, the columns walled up and 12 arches cut into the sides of the cella to give the building the nave and two aisles of a classic Christian basilica.

Gregory dedicated the new church to Saints Peter and Paul. In the late Middle Ages the church was rededicated to its builder and excellently renamed San Gregorio delle Rape, or Saint Gregory of the Turnips because the humble, ascetic Gregory was said to have tended to the vegetables of his flock. In 1748, Bourbon king Charles V of Sicily had the church dismantled and the temple restored as much as possible to its original form. Today it is considered the second best preserved Doric temple in the world after the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens which was itself converted into a Christian church in the 7th century.

Gregory dedicated the new church to Saints Peter and Paul. In the late Middle Ages the church was rededicated to its builder and excellently renamed San Gregorio delle Rape, or Saint Gregory of the Turnips because the humble, ascetic Gregory was said to have tended to the vegetables of his flock. In 1748, Bourbon king Charles V of Sicily had the church dismantled and the temple restored as much as possible to its original form. Today it is considered the second best preserved Doric temple in the world after the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens which was itself converted into a Christian church in the 7th century.

There are known Early Christian burials cut inside the temple and in catacombs outside, carved into the rocky outcroppings west of the temple much like Greek catacombs were carved east of the temple hundreds of years earlier. The skeletons unearthed this month are the first indications that there may have been Christian burials in the ground in front of the temple, which in the 7th century would have been the back of the church.