University of Cambridge historian Dr. Ulinka Rublack, author of the excellent Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe, and Maria Hayward have published a unique 16th century manuscript documenting one German accountant’s daring and elegant forays into personal style. The Klaidungsbüchlein, or “book of clothes,” is the ancestor of every fashion blog, Instagram and Tumblr and it slays them all.

University of Cambridge historian Dr. Ulinka Rublack, author of the excellent Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe, and Maria Hayward have published a unique 16th century manuscript documenting one German accountant’s daring and elegant forays into personal style. The Klaidungsbüchlein, or “book of clothes,” is the ancestor of every fashion blog, Instagram and Tumblr and it slays them all.

Matthäus Schwarz was born in Augsburg on February 20th, 1497, the son of a wine merchant and innkeeper. Even as a teenager Schwarz showed an interest in fashion, realizing how quickly trends came and went. That understanding would inspire him to meticulously record what he wearing, when and why, noting his age down to fractions of years. After learning bookkeeping through apprenticeships in Milan and Venice, as soon as he returned to Augsburg in 1516 he got a job as a clerk with Jakob Fugger, the head of one of the richest, most powerful mercantile, mining and banking firms in Europe. Schwarz quickly worked his way up, becoming head accountant by the age of 23.

Matthäus Schwarz was born in Augsburg on February 20th, 1497, the son of a wine merchant and innkeeper. Even as a teenager Schwarz showed an interest in fashion, realizing how quickly trends came and went. That understanding would inspire him to meticulously record what he wearing, when and why, noting his age down to fractions of years. After learning bookkeeping through apprenticeships in Milan and Venice, as soon as he returned to Augsburg in 1516 he got a job as a clerk with Jakob Fugger, the head of one of the richest, most powerful mercantile, mining and banking firms in Europe. Schwarz quickly worked his way up, becoming head accountant by the age of 23.

That same year he began to document his outfits, keeping a style blog in the form of illuminated manuscript. He commissioned local artist Narziss Renner, then just 19 years old, to reconstruct 36 images of him from birth through his early 20s based on detailed descriptions and old drawings. Renner then made tempera portraits of each important outfit going forward, while Schwarz made notes on the date, his age and the occasion.

That same year he began to document his outfits, keeping a style blog in the form of illuminated manuscript. He commissioned local artist Narziss Renner, then just 19 years old, to reconstruct 36 images of him from birth through his early 20s based on detailed descriptions and old drawings. Renner then made tempera portraits of each important outfit going forward, while Schwarz made notes on the date, his age and the occasion.

Schwarz took pleasure in gorgeous, expensive clothes, but they were also an important form of self-expression for him. He was successful at his job and made good money, but he wasn’t rich. He was a middle class burgher, but he spent all of his discretionary income on clothes and was involved in every aspect of the design. There was no prêt-à-porter and if there had been Schwarz still would have gone for the couture. This wasn’t just a foppish indulgence. He put on a sartorial display as a means to better himself socially. His grandfather Ulrich had pulled himself up by his

Schwarz took pleasure in gorgeous, expensive clothes, but they were also an important form of self-expression for him. He was successful at his job and made good money, but he wasn’t rich. He was a middle class burgher, but he spent all of his discretionary income on clothes and was involved in every aspect of the design. There was no prêt-à-porter and if there had been Schwarz still would have gone for the couture. This wasn’t just a foppish indulgence. He put on a sartorial display as a means to better himself socially. His grandfather Ulrich had pulled himself up by his  bootstraps, rising from common carpenter to guild leader to mayor of Augsburg only to be charged with corruption by opponents of greater wealth and status. He was convicted and hanged in 1478, a stain on the family reputation that Matthäus, like his father, felt keenly. The right kind of clothes were essential to Matthäus’ hopes that he might regain the ground lost by his grandfather’s disgrace.

bootstraps, rising from common carpenter to guild leader to mayor of Augsburg only to be charged with corruption by opponents of greater wealth and status. He was convicted and hanged in 1478, a stain on the family reputation that Matthäus, like his father, felt keenly. The right kind of clothes were essential to Matthäus’ hopes that he might regain the ground lost by his grandfather’s disgrace.

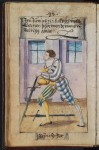

It worked. He caught the eye of Ferdinand, brother of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who invited Schwarz to his wedding. When Charles returned to Germany after a nine year absence and he and Ferdinand were in Augsburg for the Imperial Diet in 1530, ![“In March 1523 – An evening dress, the short cloak with taffeta, the doublet made from silk satin, the gray over-hose can be fitted over any hose. Hose with much green [...] small bells all around, with Matheus Herrtz, Andreas Koler, and Wolf Breitwiser. 26 years, ½ month.” © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Bild-60-107x150.jpg) Schwarz commissioned six extremely intricate outfits he hoped would please them. Schwarz’s employer Jakob Fugger was very close to the emperor, having spent huge sums to help secure his election to the office, so Schwarz wasn’t just a nameless face in the crowd. A devout Catholic in a region rent by the religious conflicts of the Reformation, Schwarz telegraphed his support for the emperor and the Church by his choice of colors. In 1541 he and two of his brothers were ennobled.

Schwarz commissioned six extremely intricate outfits he hoped would please them. Schwarz’s employer Jakob Fugger was very close to the emperor, having spent huge sums to help secure his election to the office, so Schwarz wasn’t just a nameless face in the crowd. A devout Catholic in a region rent by the religious conflicts of the Reformation, Schwarz telegraphed his support for the emperor and the Church by his choice of colors. In 1541 he and two of his brothers were ennobled.

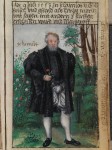

![“In June 1524 – Three types of Prussian leather as hose and over-hose, everything as shown, without doublet, but three kinds of shirts. The middle one [has attached to it] an 8 minute hour-glass on the thigh. 27 years, 22 weeks.” © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Bild-68-70-98x150.jpg) Renner and Schwarz worked together for 16 years. After that, Schwarz kept going, employing other artists, including one from Christoph Amberger’s studio, to paint his looks until 1560 when he was 63 years old. By then he had 75 pages of parchment with 137 portraits of himself, including the first secular nude since Albrecht Durer’s. It was a bold nude, too, with both front and back views and an unstinting self-assessment: “That was my real figure from behind, because I had become fat and large.” His son followed in his father’s footsteps, although he was less prolific and his styles less colorful.

Renner and Schwarz worked together for 16 years. After that, Schwarz kept going, employing other artists, including one from Christoph Amberger’s studio, to paint his looks until 1560 when he was 63 years old. By then he had 75 pages of parchment with 137 portraits of himself, including the first secular nude since Albrecht Durer’s. It was a bold nude, too, with both front and back views and an unstinting self-assessment: “That was my real figure from behind, because I had become fat and large.” His son followed in his father’s footsteps, although he was less prolific and his styles less colorful.

Schwarz had the manuscript bound in 1560 and while it was basically a personal account, he appears to have shown it to a select audience. Over the years word got out because in 1704 Sophie of Hanover, granddaughter of James I and mother of George I of England, borrowed the manuscript and had it copied by scribe J.B. Knoche. She kept a copy and gave another to her to her niece Elizabeth Charlotte of Orléans, sister-in-law of King Louis XIV of France. Sophie’s copy is now in the State Library of Hanover.

Schwarz had the manuscript bound in 1560 and while it was basically a personal account, he appears to have shown it to a select audience. Over the years word got out because in 1704 Sophie of Hanover, granddaughter of James I and mother of George I of England, borrowed the manuscript and had it copied by scribe J.B. Knoche. She kept a copy and gave another to her to her niece Elizabeth Charlotte of Orléans, sister-in-law of King Louis XIV of France. Sophie’s copy is now in the State Library of Hanover.

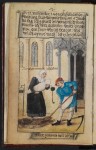

!["On 12 August 1545, this was my armor when we were inspected, around 4,500 [men]… on foot and 500 on horses, who stood in the field near the gallows for ¼ hours, 71 people in one rank in this colour. Aged 48 years, 29 weeks." © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Armour-112x150.jpg) The original is in the collection of the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig, Lower Saxony, one of the oldest museums in the world. The book is so fragile that even scholars very rarely get to see it, and then only with two trained curators gingerly turning each page. Before now, most of the color photos of the manuscript were taken from the Hanover copy. The First Book of Fashion: The Book of Clothes of Matthäus and Veit Konrad Schwarz of Augsburg is the first, and given the caution with which the manuscript is treated very possibly the last, edition to publish all the original images in color. Since the copies have notable errors in coloration that Schwarz would have been appalled by, having a full color record of the delicate original is a precious thing.

The original is in the collection of the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig, Lower Saxony, one of the oldest museums in the world. The book is so fragile that even scholars very rarely get to see it, and then only with two trained curators gingerly turning each page. Before now, most of the color photos of the manuscript were taken from the Hanover copy. The First Book of Fashion: The Book of Clothes of Matthäus and Veit Konrad Schwarz of Augsburg is the first, and given the caution with which the manuscript is treated very possibly the last, edition to publish all the original images in color. Since the copies have notable errors in coloration that Schwarz would have been appalled by, having a full color record of the delicate original is a precious thing.

The First Book of Fashion is available in hardcover and EPUB eBook from the publisher and in hardcover and Kindle from Amazon. If delayed gratification is not your bag, you can peruse Mr. Schwarz’s analog Instagram in this pdf which is a scan of the Hanover copy. The picture quality isn’t great, though.

The First Book of Fashion is available in hardcover and EPUB eBook from the publisher and in hardcover and Kindle from Amazon. If delayed gratification is not your bag, you can peruse Mr. Schwarz’s analog Instagram in this pdf which is a scan of the Hanover copy. The picture quality isn’t great, though.

Two years ago, Dr. Rublack collaborated with Tony award-winning costume designer and dress historian Jenny Tiramani, who also collaborated on the book, to recreate one of Schwarz’s most dramatic and politically significant outfits: a gold and red silk doublet over a fine linen shirt with yellow leather hose he wore for the 1530 return of the emperor. Watch this video documenting the recreation because it’s awesome. Even just putting on the outfit is crazy complicated. Oh, and killer codpiece too.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/91hysO_suRo&w=430]

The First Book of Fashion includes a pattern for the gold and red outfit, just in case you want to try your hand at recreating such a glamorous Renaissance look.