Under a cornfield in Cass County, Illinois, near where the Sangamon River flows into the Illinois, are the remains of a bustling Native American town that thrived from the 12th century through the 15th. The town had a central plaza, surrounded by three platform mounds, houses and defensive walls 10 feet tall and more than 1,000 feet long in each direction. Known as the Lawrenz Gun Club Site after a shooting club built on one of the mounds in the mid-20th century, the site has been studied by archaeologists and students from the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) every summer for six years.

Under a cornfield in Cass County, Illinois, near where the Sangamon River flows into the Illinois, are the remains of a bustling Native American town that thrived from the 12th century through the 15th. The town had a central plaza, surrounded by three platform mounds, houses and defensive walls 10 feet tall and more than 1,000 feet long in each direction. Known as the Lawrenz Gun Club Site after a shooting club built on one of the mounds in the mid-20th century, the site has been studied by archaeologists and students from the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) every summer for six years.

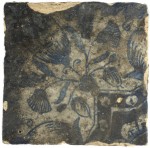

It was the remains of the mounds that first indicated a community of the Mississippian culture had once inhabited the site, but the town ranges far beyond that, covering over 26 acres. IUPUI’s archaeology field school used remote sensing technology to establish the perimeter of the site and, since they can’t dig up the whole cornfield, to identify areas likely to contain artifacts. This excavation season alone they’ve unearthed 97 bags of archaeological material including projectile points, pottery of many different kinds from cookware to storage vessels to dishes, stone tools, plant and animal remains. Only once in the six years have they encountered a human burial. Officials were notified in compliance with federal law, the grave was reburied and the remains left undisturbed.

It was the remains of the mounds that first indicated a community of the Mississippian culture had once inhabited the site, but the town ranges far beyond that, covering over 26 acres. IUPUI’s archaeology field school used remote sensing technology to establish the perimeter of the site and, since they can’t dig up the whole cornfield, to identify areas likely to contain artifacts. This excavation season alone they’ve unearthed 97 bags of archaeological material including projectile points, pottery of many different kinds from cookware to storage vessels to dishes, stone tools, plant and animal remains. Only once in the six years have they encountered a human burial. Officials were notified in compliance with federal law, the grave was reburied and the remains left undisturbed.

“The last couple of years, we have focused inside the city’s walls. This year, we are looking at earlier structures, built before the walls were put up,”” [graduate student John] Flood said. “We are looking at an early house, about 5-by-5 meters in size, and how the city started to develop, trying to understand how the very early Mississippian community arranged their structures.”

For Flood, the most fascinating part of the multi-year investigation has been the huge, elaborate defensive walls built to protect the city.

“You have several portions of walls that were constructed at different points in time. Bastions and archers’ towers, you see a change in shape as they go from more circular to more rectangular in design. It shows they are really taking their time and thinking about their defensive fortifications,” Flood said. “We see that throughout all sorts of archaeology all over the world. Usually about the time you see agriculture, things like corn or maize, all of a sudden when you have food in one location, you find you have a need to protect that food.”“You also need to make your presence known,” Flood said. “If you’re coming down the river and see a big, fortified city with 10-foot walls and archers’ towers, that’s a big mark of presence. It says ‘we’re here, and we’re here to stay.'”

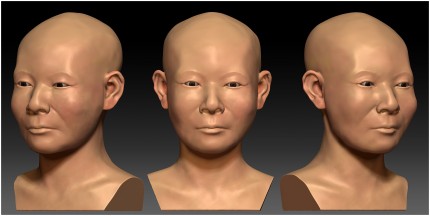

Based on the artifacts unearthed so far as, the walls and the dwellings, researchers estimate that the village had a population of 400 to 600 people from around 1100 through 1450 A.D., making it probably the largest village in the area. The inhabitants grew crops, primarily maize, and also foraged wild resources from their environment, including seeds, grasses, nuts and marshelder, a ragweed relation with edible seeds that was cultivated by the earlier Kansas City Hopewell culture of Kansas and Missouri before maize displaced it. The surrounding area also provided abundant hunting and fishing. The IUPUI team has found a great many bones of fish, waterfowl and land mammals.

Based on the artifacts unearthed so far as, the walls and the dwellings, researchers estimate that the village had a population of 400 to 600 people from around 1100 through 1450 A.D., making it probably the largest village in the area. The inhabitants grew crops, primarily maize, and also foraged wild resources from their environment, including seeds, grasses, nuts and marshelder, a ragweed relation with edible seeds that was cultivated by the earlier Kansas City Hopewell culture of Kansas and Missouri before maize displaced it. The surrounding area also provided abundant hunting and fishing. The IUPUI team has found a great many bones of fish, waterfowl and land mammals.

A large community with impressive fortifications in a fertile location with plentiful plant and animal resources, the village likely traded with the great city of Cahokia, now the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, to the north. Like Cahokia and other known Mississippian communities, the Lawrenz Site met an abrupt end in the mid-15th century. Archaeologists believe a combination of the Little Ice Age and severe drought may have brought on repeated crop failures which drove the population to abandon their settlements and seek greener pastures. With no food left to protect, fortifications that once defended the stores become prison walls enclosing only the prospect of mass starvation.

This season’s excavation will conclude at the end of the month. The 97 bags of artifacts and remains will be sorted, cleaned and analyzed in laboratory conditions back the university in Indianapolis. Every fragment is of interest as a potential source of information about the daily lives of the inhabitants of the prehistoric town.

This season’s excavation will conclude at the end of the month. The 97 bags of artifacts and remains will be sorted, cleaned and analyzed in laboratory conditions back the university in Indianapolis. Every fragment is of interest as a potential source of information about the daily lives of the inhabitants of the prehistoric town.