Before he was General Bonaparte, before he was First Consul, before he was Emperor of the French, even before the French Revolution that made it possible for a Corsican nobody to reach such dizzying heights of power, Napoleon Bonaparte was a wet-behind-the-ears graduate from the École Militaire in Paris. The first Corsican to graduate from the institution, Napoleon completed the program in one year instead of two (forced by a precipitous decline in his finances after the death of his father), so he was just 18 years old when he received his first commission as second lieutenant in the La Fère regiment in October 1785.

Before he was General Bonaparte, before he was First Consul, before he was Emperor of the French, even before the French Revolution that made it possible for a Corsican nobody to reach such dizzying heights of power, Napoleon Bonaparte was a wet-behind-the-ears graduate from the École Militaire in Paris. The first Corsican to graduate from the institution, Napoleon completed the program in one year instead of two (forced by a precipitous decline in his finances after the death of his father), so he was just 18 years old when he received his first commission as second lieutenant in the La Fère regiment in October 1785.

He was stationed in a garrison in Valence, southeastern France, where he was introduced to one Madame Grégoire du Colombier, a cultured, charming woman who saw promise in the young lieutenant and took him under her wing. From the memoirs of Emmanuel, Comte de Las Cases, who accompanied Napoleon to exile on Saint Helena and assiduously documented everything he said:

Madame du Colombier often foretold that [Napoleon] would be a distinguished man. The death of this lady happened about the time of the breaking out of the Revolution: it was an event in which she took great interest, and in her last moments was heard to say that if no misfortune befell young Napoleon, he would infallibly play a distinguished part in the events of the time. The Emperor never spoke of Madame du Colombier but with expressions of the tenderest gratitude; and he did not hesitate to acknowledge, that the valuable introductions and superior rank in society which she procured for him had great influence over his destiny.

She could have had a more personal connection to the future emperor. In early 1786, she invited him to stay at her estate at Basseaux, outside Valence, where he met her daughter Charlotte Pierrette Anne, known as Caroline. Napoleon courted Caroline du Colombier that summer and there were intimations that he might even propose. That didn’t happen, but Napoleon remembered their sweet young love until the end of his life. The Comte de Las Cases again:

She could have had a more personal connection to the future emperor. In early 1786, she invited him to stay at her estate at Basseaux, outside Valence, where he met her daughter Charlotte Pierrette Anne, known as Caroline. Napoleon courted Caroline du Colombier that summer and there were intimations that he might even propose. That didn’t happen, but Napoleon remembered their sweet young love until the end of his life. The Comte de Las Cases again:

Napoleon conceived an attachment for Mademoiselle du Colombier, who, on her part, was not insensible to his merits. It was the first love of both; and it was that kind of love which might be expected to arise at their age and with their education. “We were the most innocent creatures imaginable,” the Emperor used to say; “we contrived little meetings together; I well remember one which took place on a midsummer morning, just as daylight began to dawn, it will scarcely be believed that all our happiness consisted in eating cherries together.”

Napoleon moved on from Valence, following his career star. Caroline married Monsieur Gamparet de Bressieux, a much older former army captain, in 1792 when General Bonaparte was on his Egyptian campaign. They stayed in touch, corresponding occasionally over the years. In 1804, now Emperor Napoleon I replied warmly to a letter from Caroline de Bressieux, offering to help her brother and herself. Shortly thereafter he appointed her lady in waiting to Madame Mère, his mother Letizia Bonaparte.

Madame Junot, the Duchesse D’Abrantès, described Madame de Bressieux at court after her appointment as Letizia’s lady in waiting.

She was both witty and good and her manners were at once gentle and agreeable. I can very well understand the Emperor going to gather cherries with her at six o’clock in the morning merely to talk to her and with no less worthy motive. A thing that struck me the first time I saw her was the interest she seemed to take in the Emperor’s most trifling acts. She kept her eyes fixed upon him with an attention that could only come from the heart.

And that was a decade after their youthful romance had passed and they had married other people. One day, when Napoleon, his mother and Caroline were all together, he asked her who owned the Basseaux estate where they had spent their summer of love together. Caroline replied that her sister and brother-in-law lived there now. The Emperor expressed a desire to grant them any wish, in honor of his fond memories of the estate. Caroline declined in their name, assuring him that those happy memories were gift enough.

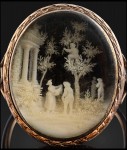

He said no more about it, but a few weeks later he presented Caroline with a token of his appreciation for all Basseaux had meant to him. It was a ring, a seemingly modest one, made of gilded bronze with a central bezel containing a miniature carved country scene under a glass cover. It was the carving, made of marine ivory, that made this ring a masterpiece. In exquisite detail, the scene depicted a group of country folk collecting fruit from trees under the shadow of an ancient temple. The fruits were, of course, cherries.

He said no more about it, but a few weeks later he presented Caroline with a token of his appreciation for all Basseaux had meant to him. It was a ring, a seemingly modest one, made of gilded bronze with a central bezel containing a miniature carved country scene under a glass cover. It was the carving, made of marine ivory, that made this ring a masterpiece. In exquisite detail, the scene depicted a group of country folk collecting fruit from trees under the shadow of an ancient temple. The fruits were, of course, cherries.

The ring stayed in Caroline’s family, a treasured heirloom, for more than 200 years. On Sunday, March 26th, the heirs sold this beautiful symbol of Napoleon before he was THE Napoleon at auction in Paris. The pre-sale estimate was 15,000-20,000 € ($16,000-21,000). It sold for 36,250 € ($38,580), a tribute to its artistry, yes, but more so the poignant sweetness of its history.

The ring stayed in Caroline’s family, a treasured heirloom, for more than 200 years. On Sunday, March 26th, the heirs sold this beautiful symbol of Napoleon before he was THE Napoleon at auction in Paris. The pre-sale estimate was 15,000-20,000 € ($16,000-21,000). It sold for 36,250 € ($38,580), a tribute to its artistry, yes, but more so the poignant sweetness of its history.