It’s been far too long since I indulged in a theme post. As total eclipse of the sun mania has struck the US, I’m jumping on the bandwagon too. The subject covers three of my favorite obsessions: the history of photography, the history of astronomy and historical firsts, all accompanied by that greatest of all obsessions, great high-resolution pictures.

William and Frederick Langenheim were born in Schöningen, Germany in 1807 and 1809 respectively. The were from a prominent family — their father Friedrich Wilhelm was mayor of Schöningen from 1808 until 1813 — but left what was then the Duchy of Brunswick in the 1830s. They immigrated to the United States and carved out careers as journalists. By 1842, they had opened a photography studio in Philadelphia.

William and Frederick Langenheim were born in Schöningen, Germany in 1807 and 1809 respectively. The were from a prominent family — their father Friedrich Wilhelm was mayor of Schöningen from 1808 until 1813 — but left what was then the Duchy of Brunswick in the 1830s. They immigrated to the United States and carved out careers as journalists. By 1842, they had opened a photography studio in Philadelphia.

The Langenheim daguerreotype studio quickly rose to preeminence in the city, thanks to the brothers’ great talent, inventiveness and embrace of new technology. In 1850 they debuted a new projectable photographic slides they called Hyalotypes. The device used to project them was a better-mousetrap version of the magic lantern which projected small drawn or painted images onto large screens. The stereopticon, as the Langenheim’s device became known, was a huge leap forward because it ![]() projected photographic images, not drawings, and because daguerreotypes capture even the most minute detail that cannot be seen with the naked eye, they could be magnified onto a screen at enormous dimensions, large enough that an auditorium of thousands could see spectacular images of, say, Niagara Falls or St. Peter’s Basilica without loss of resolution.

projected photographic images, not drawings, and because daguerreotypes capture even the most minute detail that cannot be seen with the naked eye, they could be magnified onto a screen at enormous dimensions, large enough that an auditorium of thousands could see spectacular images of, say, Niagara Falls or St. Peter’s Basilica without loss of resolution.

The brothers’ stereopticon had another feature that would prove momentous: a twin lense system that allowed the images to be faded one into the other, a smooth transition that far outshone the magic lantern’s choppy switch-overs. When they conceived of showing slides in an orderly progression, one dissolving into the other in a chronologically rational sequence, they unwittingly introduced the forerunner to the moving picture. The Langenheims charged people a dime to see pictures of natural, historical, architectural, artistic and scientific wonders projected on the big screen and the device was a huge hit.

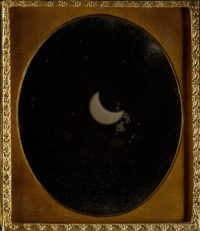

A perfect subject for the stereopticon appeared in the skies over North America on May 26th, 1854. It was a total eclipse of the sun, the first one in the US since Louis Daguerre announced his new image-fixing process in 1839. The Langenheim brothers took eight daguerreotypes of the eclipse as it progressed. Only seven of them have survived. They are now in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A perfect subject for the stereopticon appeared in the skies over North America on May 26th, 1854. It was a total eclipse of the sun, the first one in the US since Louis Daguerre announced his new image-fixing process in 1839. The Langenheim brothers took eight daguerreotypes of the eclipse as it progressed. Only seven of them have survived. They are now in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Although six other daguerreotypists and one calotypist are known to have documented the event, only these seven daguerreotypes survive. In the northern hemisphere, the moon always shadows the sun from right to left during a solar eclipse; these images therefore seem odd because they are, like all uncorrected daguerreotypes, reversed laterally as in a mirror.

It is noteworthy that these daguerreotypes are quite small, three exceptionally so. In order to produce any kind of image at all, the Langenheims were forced to use the smallest cameras available, since smaller cameras require proportionally less light and there was virtually no available light when the disk of the new moon eclipsed the largest part of the sun. The missing eighth image was probably made on the smaller plate size and showed nothing at all-a total eclipse.

As for our eclipse, now so easily captured by terrestrial and satellite technology, the National Archives in Washington, D.C. is going all out. They have secured safe solar telescopes from the National Air and Space Museum and will make them available to the public between 1:00 and 4:00PM so people can watch the eclipse up close and in total security. They’ve also created an exhibition, Solar Eclipses: Past and Present, from their pictures and records of other eclipses.

For all you eclipse watchers out there, don’t forget your protective eyewear. If you don’t have the opportunity to view the eclipse in person, you can follow its whole extraordinary path on NASA’s website.