The remains of 16 Chinese labourers from the late 19th and early 20th century have been found buried in a 1,000-year-old adobe pyramid in Lima, Peru. The bodies were discovered at the top of the Huaca Bellavista pyramid built by the Ichma people who flourished in Lima before they were conquered by the Inca in the 15th century. The pyramid was used as a clandestine cemetery by the Chinese because they were forbidden from using Catholic cemeteries. Historians believe they may have been drawn to the ancient sacred spaces which were used for high status burials when they were first built and for centuries afterwards. The remains of Chinese labourers have been found at other adobe pyramids in Lima, but this is the largest group of Chinese migrant burials ever found in Peru.

The remains of 16 Chinese labourers from the late 19th and early 20th century have been found buried in a 1,000-year-old adobe pyramid in Lima, Peru. The bodies were discovered at the top of the Huaca Bellavista pyramid built by the Ichma people who flourished in Lima before they were conquered by the Inca in the 15th century. The pyramid was used as a clandestine cemetery by the Chinese because they were forbidden from using Catholic cemeteries. Historians believe they may have been drawn to the ancient sacred spaces which were used for high status burials when they were first built and for centuries afterwards. The remains of Chinese labourers have been found at other adobe pyramids in Lima, but this is the largest group of Chinese migrant burials ever found in Peru.

In a possible sign of how the Chinese gradually emerged from dire poverty in Peru, the first 11 bodies were shrouded in cloth and placed in the ground, while the last five wore blue-green jackets and were buried in wooden coffins, [lead archaeologist Roxana] Gomez said.

“In one Chinese coffin, an opium pipe and a small ceramic vessel were included in the funerary ensemble,” said Gomez.

The opium pipe has a porcelain base decorated with blue seashells. Other grave goods discovered in the graves include an inkwell and an unusual flat wooden box that historians believe may have held an important document like his work contract. In addition to the blue-green jackets, other clothing was found on the bodies, among them cotton hats and blue jeans.

The opium pipe has a porcelain base decorated with blue seashells. Other grave goods discovered in the graves include an inkwell and an unusual flat wooden box that historians believe may have held an important document like his work contract. In addition to the blue-green jackets, other clothing was found on the bodies, among them cotton hats and blue jeans.

One of the deceased was found with a fractured skull, likely the result of violent trauma. Even broken, his skull still retained the traditional braid of hair at the base. Chinese labourers were treated abysmally and there are several cases on record of them being beaten severely. The court cases were not about owners/overseers abusing Chinese workers, mind you. It was the Chinese on trial for responding with violence to the violence inflicted on them. Perhaps this young man was a victim of a workplace “injury.”

One of the deceased was found with a fractured skull, likely the result of violent trauma. Even broken, his skull still retained the traditional braid of hair at the base. Chinese labourers were treated abysmally and there are several cases on record of them being beaten severely. The court cases were not about owners/overseers abusing Chinese workers, mind you. It was the Chinese on trial for responding with violence to the violence inflicted on them. Perhaps this young man was a victim of a workplace “injury.”

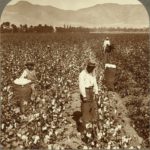

The cotton plantations in the foothills of the Andes in the Lima area were hard to farm. The land is arid desert, virtually rainless, and cannot grow any kind of crop at all without extensive irrigation systems piping water down from the mountains. Even irrigated, the land was only productive enough for two crops of cotton a year. The first was of comparatively good quality, but the manufactured product was still low-end. The second crop was worse in quality, lower in quantity and even more difficult to harvest. Harvesting by machine was not possible because the machines left too much of the bolls (the white fluffy part) behind while picking up too much of the leaves and stems that are useless in the manufacture of cotton textiles.

The cotton plantations in the foothills of the Andes in the Lima area were hard to farm. The land is arid desert, virtually rainless, and cannot grow any kind of crop at all without extensive irrigation systems piping water down from the mountains. Even irrigated, the land was only productive enough for two crops of cotton a year. The first was of comparatively good quality, but the manufactured product was still low-end. The second crop was worse in quality, lower in quantity and even more difficult to harvest. Harvesting by machine was not possible because the machines left too much of the bolls (the white fluffy part) behind while picking up too much of the leaves and stems that are useless in the manufacture of cotton textiles.

From a description on the back of a stereoscopic card of Chinese cotton plantation pickers published by Underwood & Underwood in 1900:

It has been found that Chinese laborers are the most reliable for work on a cotton plantation. They receive seventy cents, silver, per quintal (100 pounds) and they average two quintals a day. An expert picker will gather three quintals per day on the first crop of the season. On the second crop the laborers receive one dollar, silver, per quintal, because this crop is harder to pick. The cotton grown here is of medium grade, such as is used in the manufacture of coarse muslins and rough cotton goods.

With slavery abolished in 1854, the solution to the thorny question of who would willingly do this awful job for crap wages was what it always is: immigrants. Chinese indentured labourers migrated to Peru starting in 1849, when slavery was being phased out and there was a dire shortage of workers for the sugar and cotton plantations and guano mines. Just as in the United States with the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad, Chinese labour in Peru played a key role in the Guano Boom, a period of great prosperity for Peru thanks to profits from guano exports to Europe where it was highly prized as fertilizer.

In the mid-19th century, 100,000 Chinese labourers, almost entirely Cantonese men from Guangdong province, immigrated to Peru to work in brutal conditions for spare change. They were deceived into signing contracts with the promise of making a decent living only to find almost immediately they’d been lied to. The ships that transported them were called “floating hells” and the ones who survived the four-month voyage arrived riddled with disease and injury. They were immediately put to work in the plantations and mines, working from dawn until night. After 12 hours of back-breaking labour, they were locked into their quarters to keep them from running away.

In the mid-19th century, 100,000 Chinese labourers, almost entirely Cantonese men from Guangdong province, immigrated to Peru to work in brutal conditions for spare change. They were deceived into signing contracts with the promise of making a decent living only to find almost immediately they’d been lied to. The ships that transported them were called “floating hells” and the ones who survived the four-month voyage arrived riddled with disease and injury. They were immediately put to work in the plantations and mines, working from dawn until night. After 12 hours of back-breaking labour, they were locked into their quarters to keep them from running away.

Little wonder they hit the opium pipes once those doors locked, and the plantation owners encouraged the habit because they just so happened to have a monopoly on opium sales granted by the British. They couldn’t make that kind of money off of alcohol and coca.

Chinese immigration was severely restricted in 1909 and prohibited entirely in 1930. By then there was a well-established community of mixed Chinese and Peruvian heritage. Their descendants, the Tusans, still live in Peru today. Up to 3% of the population is of Chinese ancestry, more than 1,000,000 people according to the Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission, the largest ethnically Chinese community in Latin America and the seventh largest in the world. Lima has more than 6,000 Chinese restaurants that serve a unique fusion of Chinese and Peruvian cuisine and a small but thriving Chinatown (the Barrio Chino) with schools, temples, benevolent associations and multiple Chinese language periodicals.